Great Nebraska

Naturalists and Scientists

Frank H. Shoemaker

Sioux County, June 17-July 2, 1911

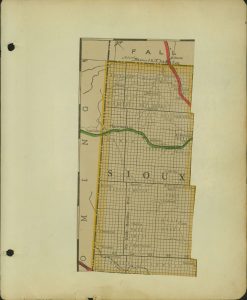

map

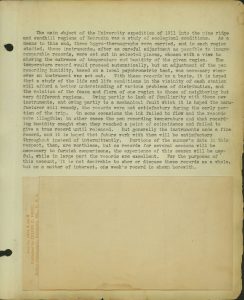

Thermograph reading

The main object of the University expedition of 1911 into the pine ridge and sandhill regions of Nebraska was a study of ecological conditions. As a means to this end, three hygro-thermographs were carried, and in each region studied, these instruments, after as careful adjustment as possible to insure comparable records, were set out in selected places, chosen with a view to showing the extremes of temperature and humidity of the given region. The temperature record would proceed automatically, but an adjustment of the pen recording humidity, based on a local psychrometric test, was necessary whenever an instrument was set out. With these records as a basis, it is hoped that a study of the life and life conditions in the vicinity of each station will afford a better understanding of various problems of distribution, and the relation of the fauna and flora of one region to those of neighboring but very different regions. Owing partly to lack of familiarity with these new instruments, and owing partly to mechanical fault, which it is hoped the manufacturer will remedy, the records were not satisfactory during the early portion of trip. On some occasions the ink failed to flow and the records were illegible; in other cases the pen recording temperature and that recording humidity caught when they reached a point of coincidence and failed to give a true record until released. But generally the instruments made a fine record, and it is hoped that future work with them will be satisfactory throughout instead of intermittently. Portions of the summer’s data in this respect, then, are worthless, but as records for several seasons will be necessary to furnish comparisons, the experience of this season will be useful, while in large part the records are excellent. For the purposes of this account, it is not desirable to show or discuss these records as a whole, but as a matter of interest, one week’s record is shown herewith.

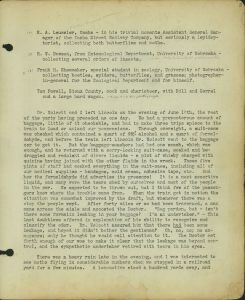

Group photograph with figures labeled 3, 6, 4, 5, 1, 2

Photo by R. J. Pool

As for other instruments carried by the party, two aneroid barometers proved to be worthless, in spite of their high credentials; one would not say a word, and the other spoke such broken English as to discredit any opinion it offered. Anemometers and instruments showing the rate of evaporation were used by the botanists. A high—and—low—temperature thermometer proved of great service to Dr. Wolcott in his study of the lake temperatures in Cherry County, and he obtained some instructive data. A water thermograph was used on Hackberry Lake, in Cherry County, giving a continuous record of the temperature at the bottom of the lake, and on readjustment, a record of temperature at lesser depths. Soundings were made of various Cherry County lakes, which, taken in connection with a rather superficial study of their fauna and flora, and supplemented by analyses of the water, have afforded a better idea of their character than we have hitherto possessed. Nets of various kinds were carried by the party, with special permits from the Governor [Ashton C. Shallenberger or Chester H. Aldrich] to Dr. Wolcott and myself to use them, but we did not find time to undertake this work.

Our party in Sioux County from June 17th to July 2nd consisted of following persons:

(1) Dr. Robt H. Wolcott, zoologist, University of Nebraska – specializing on ecology, and collecting particularly

beetles, butterflies, myriopods, reptiles, and mites.

(2) Prof. Raymond J. Pool, botanist and photographer, University of Nebraska, and

(3) Prof. Cyrus V. Williams, botanist, Nebraska Wesleyan University — collecting botanical specimens and studying various plant problems.

4) R. A. Leussler, Omaha — in his trivial moments Assistant General Manager of the Omaha Street Railway Company, but seriously a lepidopterist, collecting both butterflies and moths.

5) R. W. Dawson, from Entomological Department, University of Nebraska —

collecting several orders of insects. Frank H. Shoemaker, special student in zoology, University of Nebraska — collecting beetles, spiders, butterflies, and grasses; photographer in-general for the Zoological Department and for himself.

6) Tom Powell, Sioux County, cook and charioteer, with Bill and Sorrel and a large hard wagon.

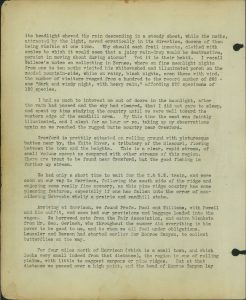

Dr. Wolcott and I left Lincoln on the evening of June 16th, the rest of the party having preceded us one day. We had a preposterous amount of baggage, little of it checkable, and had to make three trips apiece to the train to load or unload our possessions. Through oversight, a suit-case was checked which contained a quart of 95% alcohol and a quart of formaldehyde, and before the train left Lincoln Dr. Wolcott went to the baggage car to get it. But the baggage-smashers had had one smash, which was enough, and he returned with a sorry—looking suit—case, soaked and bedraggled and redolent of divers liquids — a pint of whisky charged with quinine having joined with the other fluids in the wreck. These five pints of stuff had soaked everything in the suit-case, including all of our medical supplies- bandages, cold cream, adhesive tape, etc. And how the formaldehyde did advertise its presence? It is most assertive liquid, and many were the tears shed by ourselves and most of the people in the car. We expected to be thrown out, but I think few of the passengers knew where the trouble came from. When the train got

in motion the situation was somewhat improved by the draft, but whenever there was a stop the people wept. After forty miles or so had been traversed, a man came across the aisle and accosted the Doctor. “Beg pardon, but — isn’t there some formalin leaking in your baggage? I’m an undertaker.” — This last doubtless offered in explanation of his ability to recognize and classify the odor. Dr. Wolcott assured him that there had been some leakage, and hoped it didn’t bother the gentlemen? Oh, no, no; no annoyance; only he thought he could call attention to it. The Doctor set forth enough of our woe to make it clear that the leakage was beyond control, and the sympathetic undertaker retired with tears in his eyes.

There was a heavy rain later in evening, and I was interested to see moths flying in considerable numbers when we stopped in a railroad yard for a few minutes. A locomotive stood a hundred yards away, and

its headlight showed the rain descending in a steady sheet, while the moths, attracted by the light, moved erratically in its direction, dozens of them being visible at one time. Why should such frail insects, clothed with scales to which it would seem that a juicy rain-drop would be destructive, persist in moving about during storms? Yet it is their habit. I recall Wallace‘s notes on collecting in Borneo, where on fine moonlight nights from one to ten moths visited his whitewashed and illuminated porch on the wooded mountain-side, while on

rainy, black nights, even those with wind, the number of visitors ranged from a hundred to the record number of 260 — one “dark and windy night, with heavy rain,” affording 200 specimens of 130 species.

I had so much to interest me out of doors in the moonlight, after the rain had passed and the sky had cleared, that I did not care to sleep, and spent my time studying the country until we were well toward the western edge of the sandhill area. By this time the east was faintly illuminated, and I slept for an hour or so, taking up my observations again as we reached the rugged butte county near Crawford.

Crawford is prettily situated on rolling ground with picturesque buttes near by, the White River, a tributary of the Missouri, flowing between the town and the heights. This is clear, rapid stream, of small volume except as compared with other streams of this region. There are trout to be found near Crawford, but the good fishing is farther up stream.

We had only a short time to wait for the C& N.W. [Chicago and North Western Railroad] train, and were soon on our way to Harrison, following the south side of the ridge and enjoying some really fine scenery, as this pine ridge country has some pleasing features, especially if one has fallen into the error of considering Nebraska wholly a prairie and sandhill state.

Arriving at Harrison, we found Profs. Pool and Williams, with Powell and his outfit, and soon had our provisions and baggage loaded into the wagon. We borrowed cots from the Fair Association, and extra blankets from Mr. Geo. Gerlach, who throughout the summer did everything in his power to be good to us, and to whom we all feel under obligations.Leussler and Dawson had started earlier for Monroe Canyon, to collect butterflies on the way.

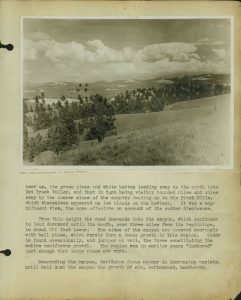

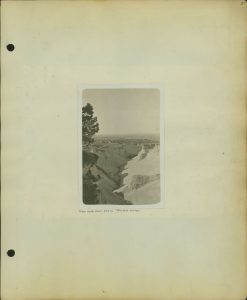

For four miles north of Harrison (which is a small town, and which looks very small indeed from that distance), the region is one of rolling plains, with little to suggest canyons or pine ridges. But at that distance we passed over a high point, and the head of Monroe Canyon lay

… Monroe Canyon

near us, its green pines and white buttes leading away to the north into Hat Creek Valley, and that in turn being visibly bounded miles and miles away by the nearer slope of the country leading up to the Black Hills, which themselves appeared as low clouds on the horizon. It was a magnificent view,

the more effective on account of its sudden disclosure.

From this height the road descends into the canyon, which continues to lead downward until its mouth, over three miles from its beginnings, is about 600 feet lower. The sides of the canyon are covered sparingly with bull pines, which rarely form a dense growth in this region. Cedar is found occasionally, and juniper as well, the three constituting the entire coniferous growth. The region was in earlier years “lumbered” just enough that large pines are rare.

Descending the canyon, deciduous forms appear in increasing variety, until well down the canyon the growth of elm, cottonwood, hackberry,

… Monroe Canyon

box elder, ash, dogwood, and cherry, might well be that of any stream of eastern Nebraska, were it not for the interpolation of black birch, mountain maple, diamond willow and other mountain species, and the occasional pine which breaks away from its true habitat to join this company. There is considerable undergrowth, and the general character of the vegetation near Monroe Creek is in striking contrast to that of the slopes even a few yards above.

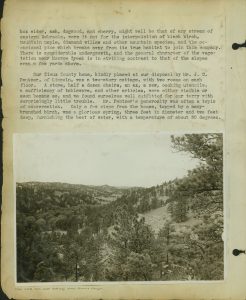

Our Sioux County home, kindly placed at our disposal by Mr. J. C. Pentzer, of Lincoln, was a two-story cottage, with two rooms on each floor. A stove, half a dozen chairs, an ax, a saw, cooking utensils, a sufficiency of tableware, and other articles, were either visible or soon became so, and we found ourselves well outfitted for our tarry with surprisingly little trouble. Mr. Pentzer’s generosity was often a topic of conversation. Only a few steps from the house, topped by a many branched birch, was a glorious spring, three feet in diameter and two feet deep, furnishing the best of water, with a temperature of about 50 degrees.

The house is on the west side of the Monroe Canyon road, which is the thoroughfare to Harrison for all the ranchers and cowboys of Hat Creek Valley and the neighboring canyons. Saturdays and Mondays are the heavy traffic days, and many teams and horsemen pass. Of course, nobody walks; that is an unknown means of locomotion. Throughout our stay we left the cottage unlocked, and the doors frequently wide open, for a full day at a time, while we departed on expeditions in various directions, and not one of our possessions was molested, though there were many handy things lying about, and notwithstanding the fact that the spring is a favorite stopping place.

Several large droves of cattle went by while we were there, as the country was so dry that change of pasture or enforced shipment to market was almost universal in that region. After one of these droves had passes, it was surprising to note how many cattle-flies had availed themselves of stopover privileges; for a day or two the road would be thickly inhabited by the pests.

The first afternoon was given over to “getting settled,” as we called the hanging and piling up, shelving, tucking in, laying on and spreading out of our multifarious possessions. The upper part of the house was not convenient for our uses, and the rear rooms was by common consent held sacred to the operations of the cook. How we ever got all of our rubbish into one small room, even inconveniently, and left space for the table in the middle, will forever remain a mystery; for mark you, while one

was in the room there was not sufficient space to see, or to think coherently, and when one went outside he had not the data visible for solution of the problem. But every member of the party proved a good fellow, and we passed sixteen happy days in this bedlam without any duels, and even with an unbelievable dearth of cuss-words.

We had arranged with Mr. and Mrs. Priddy, occupying the next ranch north, half a mile away, to furnish us bread, butter, and milk. Our other supplies came from Harrison. The bread was hard to beat — — great, white loaves, fatter out above the waist—line and crowned with gold, and toothsome to a degree the memory of which brings tears to my mental eyes. And the butter was good. But except at rare intervals, the milk — the milk! Forsooth, why will otherwise righteous cows indulge in the yucca habit! Throughout the length and breadth of this long and broad region, the yucca flourishes; and wherever it flourishes, it flourishes only until a mild—eyed bossy can wrap her prehensile and rugose tongue about the flowers and transfer them to her preliminary stomach, where with weird alchemy she starts the process of their ultimate conversion

into milk. The finished product bears an individuality which passeth understanding. Once yucca—wise, however, the victim, if he recover, is chastened and discreet; never again for him. And now comes the sad necessity of confessing that among our number there was one — I respect his family and withhold his name — who was so far departed from ways of rectitude that he “did not mind the slight flavor imparted by the yucca,” and to him and a vacillating follower or two fell the pleasure of using our daily

supply. This is a dispiriting paragraph, and I hurry on.

I did not find time to select a place on the canyon side for my bunk before dark, so I took a blanket and mosquito hood late in the evening and fared forth to lay me down and sleep. Crossing the road, I worried my way up the slope until I found a fairly level place, cleared away a few stones, and turned in. An interval of questionable duration

passed, but I awakened suddenly and moved away from there. In the dark I shook the ants from my blanket and night — gown, plucked a few skirmishers from my calves and shoulder-blades, and selected another site farther up. This was not so level, and as precaution I brought a dead pine bough to use as a wedge under my low side, and soon composed myself for rest — quite successfully this time, except that on two or three occasions I was awakened by skidding downward a few feet, which would necessitate readjustment of the wedge and rearrangement of my blanket before I could resume. On the whole, it was quite satisfactory, and much better than sleeping in a bed. I allude, however, to that portion of the night following the ant episode, which I found annoying.

At break of day I was suddenly awakened by something landing on my feet, on my knees, stomach, breast, and bang in my face — a series of five nicely spaced leaps covering a grand total of five feet seven inches in two-fifths of a second. Naturally I sat up with come alacrity to ascertain just who had done such a thing, but the whole canyon side was serene. The pines spread their fingers overhead, the logs and rocks were quite impassive, and not a beast was visible excepting a lone pinion jay who was studying me, and he nearly fell off the perch in his amazement. My first impression was that it must have been a bob-cat, but careful reasoning led me to conclude that the Volant [nimble, light, quick] intervals were too brief, and the impact rather light withal; so in the shattering of this hypothesis I was forced to conclude that it was a chipmunk. However, I woke up, and started another day, during which I selected a bed-room and moved my cot into it.

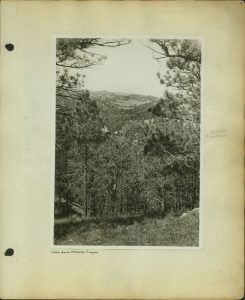

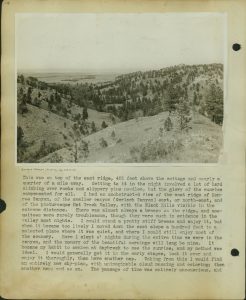

This was on top of the east ridge, 400 feet above the cottage and nearly a quarter of a mile away. Getting to it in the night involved a lot of hard climbing over rocks and slippery pine needles, but the glory if the sunrise compensated for all. I had an unobstructed view of the west ridge of Monroe Canyon, of the smaller canyon (Gerlach Canyon) east, or north-east, and of the picturesque Hat Creek Valley, with the Black Hills visible in the extreme distance. There was almost always a breeze on the ridge, and mosquitoes were rarely troublesome, though they were much in evidence in the valley most nights. I could stand a pretty stiff breeze and enjoy it, but when it became too lively I moved down the east slope a hundred feet to a selected place where it was quiet, and where I could still enjoy most of the scenery. Here I slept o’ nights during the entire time we were in the canyon, and the memory of the beautiful mornings will long be mine. It became my habit to awaken at daybreak to see the sunrise, and my method was ideal. I would generally get it in the early stages, look it over and

enjoy it thoroughly, then have another nap. Waking from this I would find an entirely new sky-plan, with unimaginable cloud massing and coloring; then another nap; and so on. The passage of time was entirely unconscious, and

the beauty of the successive cloud effects beyond description. Each morning I spent an hour and a half or two hours in this way, with peaceful catnaps of ten or fifteen minutes between the intervals of delight over the surpassing wonders of the sky and the great valley, which furnished so much room and atmosphere for the changeful tints. Then I would arise and make a bee-line — a very devious bee-line down that canyon side! – for the breakfast table, by way of the spring. On two mornings I did not awaken in time to see the sky-paintings, and these I still hold a distinct loss. Mine was the most ambitious roost of all. In vain did I descant in all

the colors of the spectrum of the beauty of the sunrise over the valley; not one other would join me in my aerie. True, Dr. Wolcott did try it one sad night, but the wind blew, and the floods, while they did not come, made feint so to do, and the good Doctor was first blown awry, and then perturbed in spirit over the impending deluge, so much so that he plucked up his bed by the

roots and decamped. It was a harrowing night.

Pool and Williams had them a small holding about half way up the canyon side, easy of access from the cottage and sheltered from the winds. Leussler lodged nearer the cottage, and as his daily talk was burdened with tales of bob-cats and mountain lions, harpies and dragons, we conjectured that his proximity to “home”

was based on prudential reasons. Dawson slumbered peacefully in the cottage night after night; no sentiment in him to eliminate the roof business and sleep out while he had a chance. Dr. Wolcott generally kept him company.

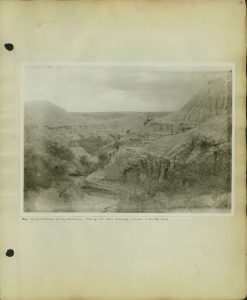

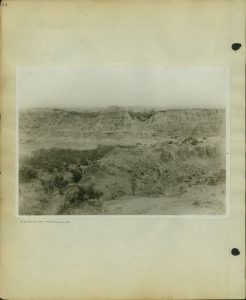

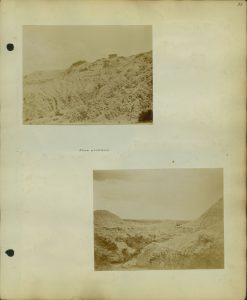

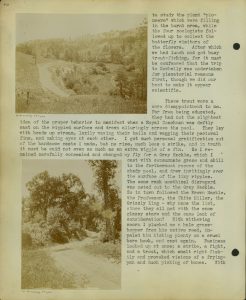

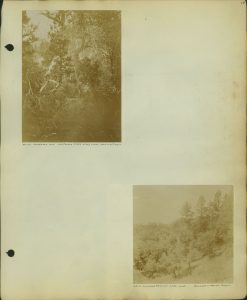

The accompanying photographs of Monroe Canyon in its varied aspects will serve far better than any attempt at description to give a true impression of the place which was our home for so many days — many to one whose vacations have always been measured by days instead of by weeks and months. These

photographs divide themselves naturally into groups: those showing the canyon as a whole, or the tops of the ridges with their pinclad buttes; those showing the features of the deciduous growth along the creek in the bottom of the canyon; and those showing bits of the roadway through the canyon. There are also some photographs dealing with special

17

subjects in detail – birds, flowers, etc.; but aside from a very indifferent effort to approximate these to the stage of the narrative, they are placed without attempt at classification, and reflect faithfully the degree of freedom, which I feel in the preparation of this ponderous document. Many of the photographs were taken on account of their ecological significance, with the pictorial feature a secondary or perhaps minus consideration. Others were taken, on the other hand, simply because their lines pleased me, and not because of any special value. Among these latter may be included the several snap-shots along the road in Monroe Canyon. Not many days had passed here before it became plain that my original estimate of films required would be inadequate, and with this happy conclusion reached I took all the foolish pictures I wanted. My supply of plates was sufficient, but I used in the first month all the films I had expected to expose in twelve weeks. The convenience and availability of the Kodak [camera] will lead even a confirmed plate user to give the lighter instrument the preference very often. — I carried two cameras. One was a 5×7 long focus box fitted with Goerz double-anastigmat lens, Ser. III, 7-in. focus, with B. & L. shutter. The other was a folding pocket Kodak taking pictures 3-1/4 x 4-1/4. Plates used were almost exclusively Cramer Iso. Inst.;[photographic negative plates] films were Eastman N.C. [non-curling film] The customary aids to photography, e.g., film and plate tanks, ray filters, exposure meter (Watkins’), were used. Autochrome plates for color photography were taken along, but I had no scales for compounding the developer — my other developers being ready mixed and not requiring weighing; so I exposed no autochromes.

Early in the afternoon of June 18th our whole party boarded the large hard wagon and took the first of a series of drives to neighboring points of interest, going on this occasion to the mouth of Monroe Canyon and southeast from there to the “bad lands” of Prairie Dog Creek. The route was indirect, as we had to make long detours to cross-intervening creeks, which all cut deep gulches in the unstable soil as soon as they emerge from the ridge. Powell knew the county well, and on this and all other trips he knew just how to reach our destination, which would have been a pretty problem without him.

All of the creeks running from the south ridge into Hat Creek Valley are fairly well timbered, and the appearance of these streams from a high point on the ridge is interesting; each stream for many miles can be traced by the growth of cottonwoods, elms, box elders, and other deciduous trees, with here and there a pine. Some of the streams start with a good volume of water from fine, cold springs, and

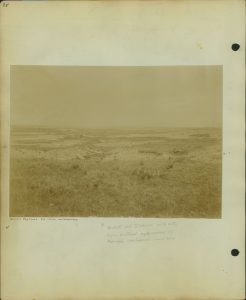

manage to maintain a flow until they connect with the main streams far out in the valley. Others, however, starting bravely enough, yield to the thirsty land after they have traversed a mile or two, beyond which there is no water, although there is a well defined creek bed, for when heavy rains come, and in the spring when the snow in the canyons melts, there is a great amount of water to be carried, and the whole region bears testimony to the frequent activity of these dry courses. The soil of Hat Creek Valley is of variable character, some of it being good land, as is evidenced by the farms scattered over it;

but the entire region is underlaid by a shale or clay which can not withstand the action of water, and such peculiarly placed regions as are subject to a sudden ingress of large volumes of water are cut and slashed in every direction, losing their surface vegetation and soil and becoming expanses of “bad lands” — a surprisingly conservative name for this western country so given to lurid nomenclature.

No reasonable amount of “conservation” will save these few peculiar regions, and no one who looks upon them will have any suggestions to offer as to their reclamation. Fortunately, the bad lands of Nebraska are of limited area, embracing comparatively few sections of land. They are limited to the western portion of the state, and more particularly the extreme northwestern

part, where they are a negligible appendage of the vast tract of similar character which exists in South Dakota. Owing to their striking features they have been made much exploited, both photographically and in a literary way, until the impression has become widespread that the Nebraska bad lands are illimitable wastes, instead of the insignificant and scattered patches which they really are.

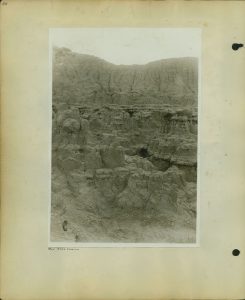

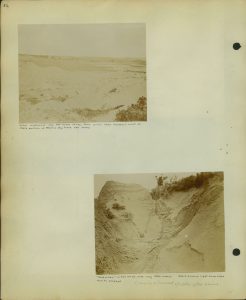

But they are none-the-less a wonderfully interesting field for study. After one look I tearfully buried every idea of conservation or reclamation, and joyfully devoted myself to viewing their wonders and using all the plates and films at hand. I made in all four trips to this region, and never came away with an unexposed film. The deep valleys, the wrinkled sides of the slopes,

the grotesque erosion, the “confusion worse confounded” where two or more drainage systems converge to effect the destruction of a given region, and most striking of all, the laying bare by the water of innumerable fossil remains, furnished an endless field for observation and photography.

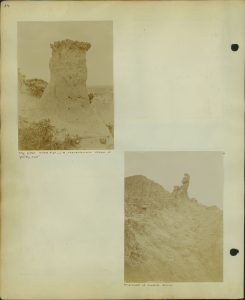

These fossil deposits are of great interest. One is impressed first by the great number of turtles, the shells of some specimens being five or six feet long, [corrected to “maximum approximately 3 feet”] I am told, though we did not find any which exceeded three feet. The problem of their geological history seems moderately simple so long as one finds only turtles, which are vastly predominant; but what happens to one’s preliminary theory when he finds the head and bones of an antelope-like creature,

and the fossil tooth of a carnivorous animal of fear-inspiring proportions? One can not imagine that these creatures were old friends of the marine turtles, and that they swam about in the same bay. So the geologists have concluded that there was a cataclysm or some such doings back in the uncanny pre—glacial days, and that these creatures of so many kinds were caught and swirled away together into this

vast dumping ground. A peculiar change has taken place in the composition of these fossil remains, many having been metamorphosed into — lime calcite? — of quartz-like appearance, and it is a striking sight to come upon one of the large carapaces glistening in the sunlight as though set with a thousand gems. Most of these fossils are very loosely held together, and crumble under the action of the frequent floods; but fine jawbones can always be found with the teeth in such perfect condition that they must

be a joy to the odontologist [dentistry].

Some springs are found in the bad lands, most of them of small flow, in some cases merely seepage from water-bearing strata. One fine spring was found in a deep-cut gulch tributary to Prairie Dog Creek; the flow of water was generous, and its quality and temperature all that could be desired. Its location was marked by one of the few pine trees of the bad lands region, and we visited it often. I took a photograph from above it, on the edge of the precipitous gulch 70 or 80 feet deep, showing the stream flowing away to lose itself in the thirsty ground within a mile.

A peculiar freak of erosion occurs at its best along this deep valley with the spring. Many pillars of shale or clay, ten or twelve feet high, stand on the brink, and are crowned with a growth of prickly pear; though it may or may not be found growing elsewhere in the immediate vicinity, it is always present on these points, so far as I had opportunity to observe.

Naturally, the insects of this region, particularly the Carabidae [ground beetles] and Cicindelidae, [tiger beetles] interested us very much, and Dr. Wolcott and I made as full collections as possible, getting among other things several species of Bembidium. At the time of writing we have done nothing toward their classification, so many interesting things which would fit nicely into this account must be omitted.

As a warning to other explorers, I give herewith photographs of Dr. Wolcott and myself, to show the awful effects of a day in the bad lands. We were both good—looking when we left camp that morning. I am trusting to the many photographs which I took in the bad lands to cover a multitude of omissions in this account, since a picture covers the subject more adequately than any number of words. I have also lumped together the photographs taken and the observations made on our several trips to this region, except that the photographs taken in August

will appear by themselves.

On the 22nd of June we drove to Sowbelly Canyon, 7 miles east of Monroe, reaching it by driving up Monroe to the ridge and following this to the upper reaches of the desired canyon. It is

impossible to reach it via Hat Creek Valley except by a much longer drive, as the water courses from the intervening canyons cut deep gulches far out into the valley. The head of each of these canyons, as shown in the accompanying photograph, is characterized by the outcropping of rocky areas.

Sowbelly Canyon is broader than any of the others, and is quite fertile, many snug little farms being

tucked away between its walls. It is also one of the most beautiful of the canyons, its east wall particularly standing out against the sky with a magnificent series of pineclad buttes. Its handsome name dates back to the days of the Sioux wars, when a body of soldiers was corralled here by the Indians and held in a state of siege and trepidation, their sole rations being bacon. When this occurred, or how many soldiers were involved, or how long the siege lasted, or how long the siege lasted, or how it was raised, are trivial points which the inhabitants have not looked into, since

they bear no relation to crops or cattle. A surprising ignorance of local history was encountered wherever we tried to get data of this character throughout the summer, and such “facts” as we did get were so badly damaged that I have not used them.

On the way down the canyon we found a perfectly beautiful burro hitched to a handsome

phaeton, and Prof. Williams availed himself of the opportunity to get a really good setting for a portrait — or group, as you like — the result appearing herewith.

We passed the site of an extensive fire of a year ago among the pines, and the botanists

stopped

to study the plant “pioneers” which were filling in the burnt area, while the four zoologists followed up to collect the butterfly visitors of the flowers. After which we had lunch and got busy trout-fishing, for it must be confessed that the trip to Sowbelly was undertaken for piscatorial reasons first, though we did our best to make it appear scientific.

These trout were a sore disappointment to me. Far from being educated, they had not the slightest idea of the proper behavior to manifest when a Royal Coachman [fishing fly] was deftly cast on the rippled surface and drawn alluringly across the pool. They lay with heads up stream, lazily waving their tails and wagging their pectoral fins, and making eyes at each other. I got much personal gratification out of the handsome casts I made, but no rise, much less a strike, and in truth it must be said not even so much as an extra wiggle of a fin. So I remained carefully concealed and changed my fly for a Gray Hackle [fishing fly],

which I cast with consummate grace and skill to the farthermost recess of the shady pool, and drew invitingly over the surface of the tiny ripples. The same rank unethical disregard was meted out to the Gray Hackle. So in turn followed the Brown Hackle, the Professor, the White Miller, the Grizzly Kind — why name the list, since they all met with the same glassy stare and the same lack of consideration? With withering scorn I plucked me a hale grasshopper from his native reed, impaled him kicking plenty

on a cruel bare hook, and cast again. Business looked up at once; a strike, a fight, and a trout, which smelt right fishily and provoked visions of a frying pan and much picking of bones. With

a prayer and an apology to the sainted Izaak Walton [1593-1683, author of The Compleat Angler, 1653] — who at any rate should a heap sight more be a saint than some of those elected — I tucked away my flies and fared forth to collect grasshoppers.

But it was a day of humility all around; if I was humbled by the forswearing of gentlemen’s bait and the adoption of vulgar, goggle eyed, parasitized, tobacco-spitting grasshoppers, what must have been the feelings of the botanists, who forswore their allegiance to Green Things and became for the nonce most energetic collectors of said loathsome grasshoppers? For be it known, orthopterious crop was sparse, and it generally took longer to round up a grasshopper than it did to make connections with a trout after the bait was secured.

So while Dr. Wolcott and I whipped the stream and had all the fun, Profs. Pool. and Williams and Mr. Leussler took the butterfly nets and worked far harder afield to keep us supplied with bait. Their conduct was simply perfect, for not only did they steal up quietly with the

hard—earned bait, but they guardedly spoke words of commendation and even applause when we landed a fish, in a manner most tickling to our vanity. It was great sport, and I don’t care if Dr. Wolcott did catch more than I; it simply shows that he is accustomed to more plebeian methods, which is noting to brag of. If those trout had been versed in orthodox piscatology I would have shown him!

So with much bait-collecting, some fishing, a little botanizing, zoologizing, and photography, we passed the day, returning home late in the evening. We did not have a very large mess of fish for seven of us — I believe there were 17 in all — for many of those caught were too small to keep, and the largest were about twelve inches long; but we all enjoyed the expedition, and the perfect manner in which Prof. Pool fried the fish entitles him to our lasting gratitude.

On June 29th another trip to Sowbelly Canyon was made. Several reasons of the class known as specious were advanced. Among these was the fact that the botanists had had poor luck with their photographs on the first trip; another reason, the vast number of Untranslated Facts to be found in that wonderful

region, which we had barely touched, etc. I do not know that anyone had the hardihood to go back of the returns and show up the true reasons — which, by the way, was altogether Pool’s fault; he should not have cooked ’em so perfectly. So everybody got into the large hard wagon, excepting Dr. Wolcott and myself; it was out plan to walk to Sowbelly Canyon by the Hat Creek Valley route, collecting tiger beetles for a time near Prairie Dog Creek, getting a few photographs in the bad lands, and connecting with our party in time

for lunch. It was a pretty plan.

By the time we had visited the tiger beetles and the near portion of the bad lands, it was 11 o’clock, and we thought it wise to move on toward lunch. So we made for the prominent butte shown in the lower photograph on page 24, which we supposed to be the butte standing at the west portal of Sowbelly Canyon. Rounding this point at last, after a longer walk than it would have seemed possible

to crowd into the space, we were surprised to find that the region beyond bore little resemblance to Sowbelly Canyon; there was no stream, and only a narrow draw where there should have been a wide

one. So we made our way to the next prominent buttes east, beyond which we believed must certainly lie the country we sought. The question then arose as to the preferable means to entering the canyon — whether it were better to climb the ridge just south of the butte, or to take the

longer and level way around into the mouth of the canyon. Dr. Wolcott favored the former course, while I preferred the latter; but as I am nothin’ if not polite, and therefore frequently nothin’, I withdrew my plan of campaign and followed him over the ridge. When we got safely down the other side, we were nowhere in particular, as nearly as we could determine. The region did not resemble Sowbelly Canyon. Having started wrong, we steadfastly persisted in our course, cutting across ridges instead of taking the long walk around, and this led to a fine, rugged piece of climbing – across slippery ridges, over rocky buttes, and down narrow creek-beds choked with fallen trees and the drift of freshets; finally landing, after traversing many ridges, in a fairly respectable canyon with a stream and a road. But the road was unused and the stream was small, by which tokens it was borne in upon us that we had not yet caught up with our lunch. When the early navigators landed on the Atlantic seaboard and cut across the sand-dunes of sometime Maryland to find the Pacific Ocean, they must have found in Chesapeake Bay somewhat of the disappointment we found in Spring Creek Canyon. It was good enough in its way, but not just what we were looking for. So we sorrowfully cut across a few more ridges, and by great good fortune did, in the course of time

chance upon Sowbelly Canyon.

For explanation of our error, note the photographs on page 42, showing a view to the westward of the butte west of the mouth of Sowbelly Canyon; then examine the photograph at the foot of page 24, a view eastward, showing in the distance the butte for which we had headed on leaving the bad lands. There is

striking similarity between the two buttes, and after having seen that at the mouth of Sowbelly Canyon it had not occurred to us to doubt that it was the one visible from the bad lands.

It was well after three o’clock when we reached Sowbelly Canyon, and we began fishing as soon as possible, repeating in the main the program of our previous trip and spending several pleasant hours.

June 27th was devoted to a drive to Warbonnet Canyon, five miles west of Monroe. Our road lay well out in Hat Creek Valley, and we greatly enjoyed the view of the picturesque south ridge as we passed along

several miles of it. Warbonnet is the wildest, deepest, most densely vegetated, and altogether the most interesting of the canyons visited in

this region; it is in the recesses of its deep valleys that Transition conditions are to be found if anywhere in the state, but it is too early to decide this point. The road is delightfully bad, with sharp turns and steep climbs and descents and bad bridges; low branches and dense overhanging masses of vines kept us ducking for our lives. Less blasé roadsters than Bill and Sorrel would have gone crazy and run away, but they understood their business and stuck to it. We drove up the canyon for about

two miles, where we camped and had lunch, after which each acquitted himself according to his desire — Leussler and Dawson following the valley in search of butterflies, Pool and Williams visiting the high points for plants, and Dr. Wolcott and I confining our attention chiefly to the lowest and dampest regions in search of beetles. We got a fine series of the beautiful Cychrus elevatus , [beetles genus] collecting thirty or more, whereas my entire previous takings about Omaha and Lincoln had been about eight specimens. The specimens here were much darker than those I had seen previously. In one deep gulch, only a few yards above the level of the valley,

we found numerous bones of bison, and one well preserved skull. I took numerous photographs of high points and attractive vistas. The day passed too quickly, and it is a temptation to go into detail about certain points of interest. Well up the canyon we found evidence of beaver work in past years, and on the way home we followed Warbonnet Creek far out into Hat Creek Valley to see their more recent work; but as this subject was given special attention on our trip to this region in August, when numerous photographs were taken, I leave the entire matter for presentation in the August notes.

Dr. Wolcott and I made another trip to Warbonnet on the afternoon of July 1st, to get one or two photographs especially desired and to bring in the instrument stationed there.

The day was cloudy and dark, a most confusing light for photography, the “initial factor” for exposure being so long that I could not use my exposure meter, and had to use my judgment instead. One of the photographs taken was of the pits of the ant-lions. (the larvae of Myrmaleonidae) [mymeleiontidae, neuropteran, antlions] , 400 or 500 feet up the side of the canyon and at the base of a sheer cliff at least 100 feet high, the shelter of which had led them to adopt this odd site. Another photograph shows the base of this cliff and the steep slope leading down from it. Still another shows the site of our instrument station in the canyon, on the bank of Warbonnet Creek, with a peculiar association of elm, black birch, and quaking aspen.

In addition to these long drives, we of course made many shorter trips in various directions, individually or in groups of two or three, or occasionally the whole party. Dr. Wolcott and I generally went together on account of our common interests, and many such trips

will not be made the subject of special notes, the results instead showing up in our collections and photographs. A few of these little journeys, however, deserve mention.

On June 20th Dr. Wolcott, Dawson and I went out almost to Prairie Dog Creek, the bad lands being our objective point; but I had the good fortune to chance upon a colony of tiger beetles — Cicindela cinctipennis [grass-runner tiger beetle] —

showing remarkable range of variation, and forthwith we settled down and spent our entire remaining time collecting these specimens, each

getting fifty or more. They were found over an area 50 yards wide and 200 yards long,

bordering a dense growth of Symphoricarpos [common snowberry], the soil of this region having been worked over pretty thoroughly by pocket gophers the previous year. On the bare patches where the gopher hills had been washed down, and among the scattered growth of grasses and milkweeds, we found

the beetles. They indulged in rather short flights, but were hard to see and sufficiently

active to make their capture difficult. The same species we had found sparingly in the bad lands on other trips, but this proved to be our best opportunity for collecting them, and we secured quite satisfactory series. — In the late afternoon of the same day Dr. Wolcott and I took a walk out Monroe Creek, following it for five miles, on a trout fishing expedition, but it was exasperating work, for the creek was densely overgrown at almost every point, and it was only at

intervals that we could find space to drop a line — casting being entirely out of the question. We did not succeed brilliantly, but finally got a “mess” — a delightfully flexible word. — During the evening of June 24th we made a similar trip, with a like degree of moderate success.

On June 25th we went to Kiel’s ranch, a mile and a half out in the valley, to collect a wonderfully varied lot of coccinellid beetles (“lady-birds”) [ladybird beetles] which Dr. Wolcott had located on a previous trip. They were found on the leaves of the box elders, and the variety was amazing — at least a dozen species, and generally each species showing a great range of variation. A peculiar feature of their distribution was its sharp definition; though there were box elders in all directions, and the conditions apparently the same throughout, the beetles were confined to a given area. Many of the box elders in this region

were disfigured by the large scars, and example of which is shown at the foot of the preceding page.

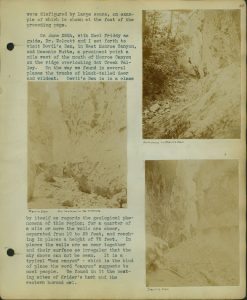

On June 28th, with Noel Priddy as guide, Dr. Wolcott and I set forth to visit Devil’s Den, in West Monroe Canyon, and Masonic Butte, a prominent point a mile west of the mouth of Monroe Canyon on the ridge overlooking Hat Creek Valley. On the way we found in several places the tracks of black-tailed deer and wildcat. Devil’s Den is in a class

by itself as regards the geological phenomena of this region; for a quarter of a mile or more the walls are sheer, separated from 10 to 25 feet, and reaching in places a height of 75 feet. In places the walls are so near together and their surface so irregular that the sky above can not be seen. It is a typical “box canyon” — which is the kind of place the word “canyon” suggests to most people. We found in it the nesting sites of Krider’s hawk and the western horned owl.

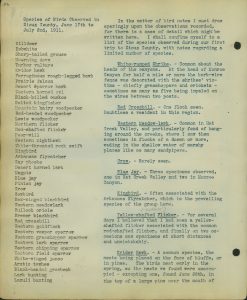

Species of Birds Observed in Sioux County, June 17th to July 2nd, 1911.

- Killdeer

- Bobwhite

- Sharp-tailed grouse

- Mourning dove

- Turkey vulture

- Krider hawk

- Ferruginous rough-legged hawk

- Prairie falcon

- Desert sparrow hawk

- Western horned owl

- Black-billed cuckoo

- Belted kingfisher

- Mountain hairy woodpecker

- Red-headed woodpecker

- Lewis woodpecker

- Northern flicker

- Red-shafted flicker

- Poor-will

- Western nighthawk

- White-throated rock swift

- Kingbird

- Arkansas flycatcher

- Say phoebe

- Desert horned lark

- Magpie

- Blue jay

- Pinion jay

- Crow

- Cowbird

- Red-winged blackbird

- Western meadowlark

- Bullock oriole

- Brewer blackbird

- Red crossbill

- Western goldfinch

- Western vesper sparrow

- Western grasshopper sparrow

- Western lark sparrow

- Western chipping sparrow

- Western field sparrow

- White-ringed junco

- Arctic towhee

- Black-headed grosbeak

- Lark bunting

- Laruli bunting

In the matter of bird notes I must draw sparingly upon the observations recorded,

for there is a mass of detail, which might be written here. I shall confine myself

to a list of species observed during our first trip to Sioux County, with notes regarding a limited number of species.

- White-rumped Shrike. —

Common about the heads of the canyons. At the head of Monroe Canyon for half a mile or more the barb—wire fence was decorated with the shrikes victims—

chiefly grasshoppers and crickets — sometimes as many as five being impaled on the

wires between two posts. - Red Crossbill. —

One flock seen. Doubtless a resident in this region. - Western Meadow-lark. —

Common in Hat Creek Valley, and particularly fond of hanging around the creeks, where I saw them sometimes in

flocks of a dozen or more, wading in the shallow water of marshy places like so many

sandpipers. - Crow. —

Rarely seen. - Blue Jay. —

Three specimens observed, one in Hat Creek Valley and two in Monroe Canyon. - Kingbird. —

Often associated with the Arkansas flycatcher, which is the prevailing species of the group here. - Yellow-shafted Flicker. —

For several days I believed that I had been a yellow-shafted flicker associated with the common red-shafted flicker, and finally on two occasions saw specimens at short distances and unmistakably. - Krider Hawk. — A common species, the nests being placed on the face of bluffs, or in pines. The

birds nest early in the spring, so the nests we found were unoccupied- excepting one,

found June 28th, in the top of a large pine near the mouth of

- Louisiana tanager

- Violet-green swallow

- Cliff swallow

- Barn swallow

- Bank swallow

- White-rumped shrike

- Red-eyed vireo

- Western warbling viree

- Plumbeous viero

- Audubon warbler

- Yellow warbler

- Ovenbird

- Western yellowthroat

- Long-tailed chat

- Redstart

- Catbird

- Brown thrasher

- Rook wren

- Western house wren

- Rocky Mountain nuthatch

- Townsend solitaire

- Long-tailed chickadee

- Robin

- Western robin

- Mountain bluebird

Monroe Canyon.

With the aid of a glass we could see from a neighboring height that it contained one

or possibly two eggs. Our time was short and we did not climb the tree, and unfortunately

did not visit it again. The more characteristic location, however, for nests of this

species is on ledges. The photographs on page 19 show a bluff with a nest, and the

photographs on this page show the same nest, taken from the top of a pine growing

near the base of the bluff.

- Bob-white. — Occasional in the canyons.

- Killdeer. —

Two or three observed along creeks leading into the bad lands.

Western Robin, and Eastern Robin. – Both found, the latter not common. - Townsend Solitaire. — Resident here; not often seen.

- Rock Wren. —

Common along ledges at tops of ridges. - Audubon Warbler. —

Fairly common in canyons

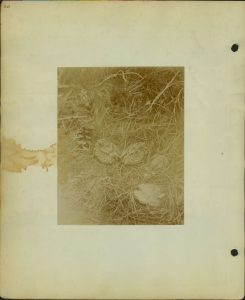

- Plumbeous Vireo. —

A nest with four eggs found June 20th, in box elder above road in Monroe Canyon. The mother bird sat very closely, peering over the edge of the nest as we pulled

down the branch to investigate. Hatched in due course. - Violet-green Swallow. —

Occasionally seen. - Lazuli Bunting. —

One seen at Crawford in city park. - Black-headed Grosbeak. —

Fairly common. - White- winged Junco. —

Often seen; doubtless nests in these canyons. - Bullock Oriole. —

Occasionally seen. - Pinion Jay. —

The characteristic bird of the region, and a great favorite with us all. They possess

the habits and vocal abilities of the jay tribe, and were so common that mental picture

of Monroe Canyon always contains at least one. Their notes are more softly modulated than those of

the blue jay, their favorite remark being “queevy—quavey, queevy—quavey,” or under

stress of great excitement — which is a common state of all jays — this may be rendered

“queevy queevy queevy queevy queevy” — perhaps a dozen times in succession if the

attendant circumstances are extremely hazardous, remarkable, or scandalous. When I

awoke mornings in my sky bed—room it was common to find a committee of half a dozen

of the birds camped about the neighboring branches, and by pretending to be still

very much asleep I frequently got fine views of the jays, which is ordinarily difficult

of accomplishment, as they are very shy. At the first movement they would queevy—queevy

into the distance with great alacrity. — Leussler added his mite to ornithological lore by saying that the species was very common

about Omaha, where, however, they are called “opinionated jays” — which will do for him. - Magpie,. — Fairly common, but moreso on the other side of the ridge in the Glen region.

- Say Phoebe. — Chiefly in Hat Creek Valley.

- White-throated Rock Swift. — Fairly common about high points of buttes on ridges.

Poor—will. — Common. We had a poor-will concert every evening, and all night long. The note is plaintive and beautiful —

an odd combination of words, but willfully put down —

and it was not uncommon to have a dozen of the birds at once within hearing. Late

one night — one of the nights when Dr. Wolcott tore himself away from the cottage —

we were making our way up the side of the canyon when we flushed a poor—will, which flew or fluttered near us for some distance, so we marked the place as worthy

of

investigation. On the way down in the morning I visited the region, and the bird flew

from the ground as I approached the place from which we had startled it the night

before. The dead top of a storm-beaten pine, twisted and misshapen, lay on the canyon

side, and under this I found two baby poor—wills, the quaintest little creatures in the whole world. They cuddled close to the ground

and lay with closed eyes, motionless and shapeless, until touched, when their eyes

suddenly opened and with wide—spread wings they weaved from side to side in the oddest

way, uttering an almost inaudible note somewhat suggesting the note of alarm which

the mother bird had sounded when scared from the “nest.” Of course there was no nest;

the little ones rested on the pine needles, with half an egg—shell still by them.

It did not take my long to get my cameras and engage myself with this delightful photographic

subject. But in spite of repeated efforts to photograph the mother bird, I did not

succeed. I set the camera focused on the young birds and ready for exposure of the

plate, and on cautiously returning found that the mother bird had moved the family

several feet away, not liking the strange object in her dooryard. A repetition of

the effort produced identical results, and several trials to get a kodak shot at the

mother bird were thwarted by her watchfulness; on each occasion she flew before I

reached the desired point. But the young were good subjects, and I secured several

photographs.

After the first day’s many visits — for I devoted much of it to this little family

— the mother bird moved the household several yards along the side of the canyon,

and on several successive days I had a delightful pastime each morning hunting out

the new quarters. This trackless trailing was great sport, and not the easiest hunting

imaginable, for the canyon side was littered with rocks, fallen trees, and branches,

and well provided with sheltering grasses and other vegetation. On the third morning

the young had reached a point about forty yards from the nesting place; and on the

fourth morning they were not to be found.

Western Horned Owl. — Very much in evidence in the evenings and during the nights. One evening while

it was still quite light I heard the hooting of an owl on the east side of Monroe Canyon, which was promptly answered by one on the west side, half a mile away. After exchanging

ideas for a few minutes the owl on the west side crossed to the east. I could see

it plainly against the sky, and twice while on the wing I hear it utter its call.

Without any special reason for the belief, I had always supposed that this call was

given from a perch of some kind; it is such a big, deep—toned note that it would seem

reasonable to suppose that the bird must hang on hard the while, and this easy flight

with the call uttered en route came as a distinct surprise.

A great number of notes regarding insects observed might be given here, but our collections

have not yet been worked up and the data would be unsatisfactory and incomplete. Even

our butterfly list is full of question—marks, and we have hundreds of specimens to

relax, spread, and study before the list will mean much, so it is omitted.

As for the mammals of the region, wildcat and deer (white—tailed) tracks have already

been mentioned; we did not see these animals. Prairie dog towns are found in Hat Creek Valley at various places. Coyotes were heard occasionally in the evenings, but their numbers

have been greatly diminished by the ranchers. One early afternoon in the bad lands

a coyote trotted across the sage plain near us, not seeing us until within a hundred

feet; he very slightly increased his pace and altered his course, giving us suspicious

sidelong glances until safely past. Chipmunks were very common in the canyons and

occasional in the bad lands. Bison bones and horns were found at various places, in

the canyons and in Hat Creek Valley. Edouard Priddy informed us that several antelope had been seen recently in the western part of the

county, near the Wyoming line. Mountain lions were formerly found in the canyons,

and a horse owned by Mr. Priddy bears heavy scars caused by the attack of one of these animals within two or three

years; but if they are still here they must be very rare. Beaver work was found in

nearly every creek in the region, and my notes for August will cover this subject

at length.

Garter—snakes of a western variety which we have not yet determined were fairly common.

Bull—snakes were seen occasionally, both in Monroe Canyon and in Hat Creek Valley. One blue-racer was seen in Monroe Canyon, but it got into a deep hole before I could get within reach of it. In spite of careful

search and constant watchfulness, no rattle—snakes were seen.

64

65

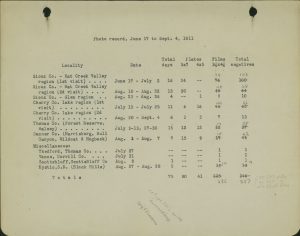

Photo record, June 17 to Sept. 4, 1911

| Locality | Date | Total days |

Plates ?5×7 4×5 |

Films 3 1/4x 4 1/2 |

Total negatives |

|

| Sioux Co. — Hat Creek Valley region (1st visit)…. |

June 17 — July 2 | 16 | 24 | — | ||

| Sioux Co. — Hat Creek Valley region (2nd visit)…. |

Aug. 10 — Aug. 22 | 13 | 20 | — | ||

| Sioux Co. — Glen Region. | Aug. 23 — Aug. 26 | 4 | — | 1 | 9 | 10 |

| Cherry Co. — lake region (2nd visit)……… |

July 15 — July 25 | 11 | 6 | 16 | ||

| Thomas Co. (Forest Reserve, Halsey)……… |

July 3 – July 13, 27-30 | 15 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Banner Co. (Harrisburg, Bull Canyon, Wildcat (amper) Hogback) |

Aug. 1 – Aug. 7 | 7 | 15 | 9 | ||

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| Thedford, Thomas Co…. | July 27 | — | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Vance, Morrill Co…. | July 27 | — | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Scottsbluff, Scottsbluff Co | Aug. 8 | 1 | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Mystic, S.D. (Black Hills) | Aug. 27 – Aug. 28 | 2 | — | — | ||

| Totals | 75 | 80 | 41 |

41 4×5 ”

236 3 1/4 x 4 1/2 films

corrections

????