Great Nebraska

Naturalists and ScientistsFrank H. Shoemaker

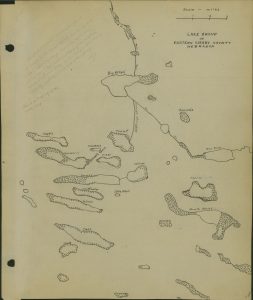

Cherry County, July 13-July 26, 1911

cover

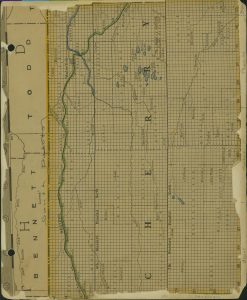

map

photograph

photograph

III group, of VII areas visible and recorded in 1911. FHS

On the evening of July 13th 1911, Dr. Wolcott, Prof. Williams and I left Cover and title

page missing. This is the No. III group, of VII areas visited and recorded in 1911.

FHS Halsey for the Cherry County lakes, Prof. Pool having decided to remain at the Forest Reserve.

We spent the night at Thedford, and early on the morning of the 14th took the Brownlee “stage”

— another loose word, applied throughout this region to any vehicle making theoretically regular trips over a given route with mail or freight. In this instance it was a three-seated light wagon, with enough passengers and baggage to fill it uncomfortably. We started in a light rain, and showers continued most of the day.

The country for a few miles north of Thedford is practically free from blow-outs and shifting areas, the sand being held in place by the vegetation, which is more varied and better established than in most of the sandhill area which we visited. Many flowers were in bloom, the

most striking being the big “bush morning—glory,” large patches of Amorpha canescens, and everywhere the pretty heads of Kuhnisteracandida and purpurea.

We reached Brownlee after a thirty-mile drive at about 12:30, had “dinner” there, and went on with Rivers Stilwel, who had driven the thirty miles from his ranch to meet us. He had a large wagon and four horses, so the going was much easier than the first half of the trip.

Along our route were many evidences of great destruction by the hailstorm of the 12th. Corn

was almost ruined, and the grass on every slope was laid flat and all combed one way by the

rush of water, for a heavy rain had followed the hail.

We passed by Dad’s, Little Alkali, Dewey, and Clear Lakes, which looked very interesting to

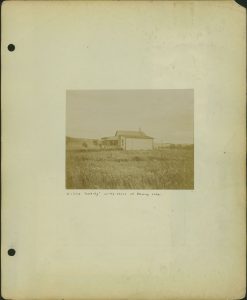

me after the eight years’ interval since my last visit, but of course we could not stop — though the presence of a nesting colony of grebes at the east end of Dad’s Lake afforded a great temptation. We finished our sixty-mile drive at Stilwel’s ranch at 6 p.m. central time. When I last visited this region, in 1903, Mr. Stilwel occupied a soddy on the bank of Hackberry Lake, and our quarters were in another soddy near by arranged for accommodation of hunters. In 1907, however, the water in the lake rose several feet, and the old place was abandoned for the present location, near the lake shore a quarter of a mile farther north, where a comfortable two-story frame house was erected.

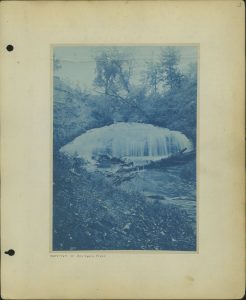

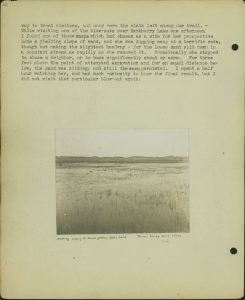

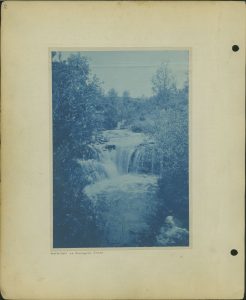

Cherry County contains 5668 square miles — half the area of Maryland, or Belgium. The Niobrara River — on the old maps as “L’Eau qui Court, Rapid, or Niobrara River” — runs from west to east across the northern portion of the county. Along this river and north thereof are plains conditions, with pine trees and rocky outcroppings; south of it the sandhills begin and continue to and far beyond the southern boundary. There are several tributaries; the Snake River, and Gordon’s and Schlegel’s [sic] Creeks. We did not visit these streams during the present visit, but there are shown herewith two photographs taken in 1903 of small waterfalls on Schlegel’s [sic] Creek.

2

Watefall on Schlegel’s [sic] Creek

Watefall on Schlegel’s [sic] Creek

Everything here is on a bigger scale than in the Thomas County sand-hills — more room, more numerous and larger blow-outs, more yucca and cactus. Near the eastern edge of the county lies the group of lakes which we visited. In the southwestern portion of the county is a lake system reputed to be even larger and less harried by civilization.

This entire region is underlaid by a hard stratum, rising gradually to the westward. In most of the area the sandhills cover this stratum uniformly, but where a valley cuts low enough through the hills to reach sufficient moisture, a luxuriant growth of grasses has laid hold upon the sand and a fine “hay valley” is the result. Where the cut is still deeper a lake is formed. These lakes are uniformly fed by seepage, occasionally by springs, at the western end — or rather the northwestern end, for with interesting frequency they are elongate in form and their general directions in from northwest to southeast. Ordinarily the northwest end is characterized by a boggy tract, filled with ferns, until a point near the water is reached, where there is an area of treacherous black mud. The lakes vary remarkably in the character of the water, and correspondingly in the animal and plant life which they maintain. Chemical analyses have shown that the degree of alkalinity varies greatly, the water of some

of the lakes containing twenty times as much alkali as that of other lakes; and strangely enough, a

comparatively fresh and a markedly alkaline lake may be found near neighbors, and to all appearances drawing upon the same subterranean sources for their water supply.

Aside from the pines of the plains and ridges north, and the deciduous growth, which marks the course of each stream, Cherry County is almost bare of trees. In the lake region there is an occasional wreck of a “tree claim,” with shattered ranks of cottonwoods, and in

some places these trees have grown quite well; but aside from these planted trees; and away from

the streams, trees are very rare, an occasional hackberry being found on a sheltered hillside,

or a clump of plum-trees on the hill slopes south of the lakes.

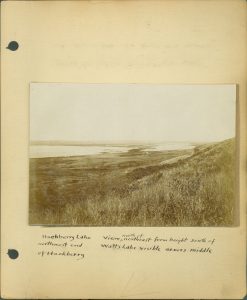

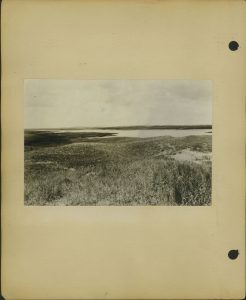

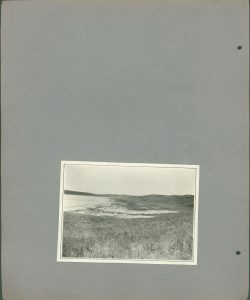

Hackberry Lake, being the most convenient as well as one of the most interesting lakes, received more of our attention than any other lake. It is one of the freshest of this lake group, of which there are twenty-one altogether. Three of four of these lakes bearing names are mere marshes, while there are numerous clear-water ponds which on account of their small size are not dignified by names. Hackberry Lake is two and a half miles long and about a mile wide. The greatest depth found by Dr. Wolcott during extensive investigations was seven feet. The general direction of the lake is from northwest to southeast, but I have elided this in my notes to north and south, and will keep up the bad habit. The north side is bordered throughout its extent with a growth of tules, [reeds] varying in breadth from a mere fringe to several hundred yards, while the south side is almost barren of this growth. This might seem to be again the work of the northwest wind, but not all of the lakes bear out this

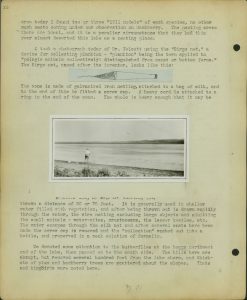

Hackberry Lake northwest end of Hackberry View north of northeast from height south of Watt’s Lake visible across middle

[No caption}

Hackberry Lake View northwest from southeast and Stillwell’s ranch house visible on right

theory, and as that malicious wind has enough crimes definitely charged to it, this one opportunity of giving it the benefit of the doubt is cheerfully welcomed. The lake bottom is covered, throughout most of its extent, with Myriophyllum and Chara, and in places Lemna and Potamo-geton; and this submarine garden, though simple enough in its tones of green and yellow, is of surprising beauty when viewed under the right conditions of light. This vegetation furnishes a hiding-place for multitudes of black bass, only they don’t hide; they are the most con—spicuous black bass I ever met, spending a large part of their time jumping out of the water. But I must not start on the bass subject now; it deserves and will receive special attention later.

Near its center the lake is almost cut in two by a band of tules, which mark shallow water, and it is quite probable that before many years have passed the division will be complete, for there certainly has been a marked tendency in that direction within the past eight years.

Hackberry is one of the favorite lakes of the duck hunters, the thick growth of tules affording both an attraction to the ducks and concealment for the hunters. During the early spring and late fall, Stilwel’s establishment is filled to its limit with hunters, sometimes

twenty or twenty-five at once.

On July 15th our party started out at 7:15 a.m. along the north shore of Hackberry Lake. The day was clear and cool, with a slight wind from the southwest. Our first find of note was a

collection of Histeridae and Silphidae — beetles which perform the useful but inglorious duty of making away with dead animal matter. This particular lot was reveling in the shattered dry body of a turtle. Next we rounded up several specimens of a species *

of Elaphrus — beetles which inhabit wet sand or mud; a commonplace little brownish fellow until viewed under a lens, when a first observer is amazed to find the seeming brown a wonderful harmony of green and violet and bronze. The whole beetle tribe is full of these surprises, and it should be writ down a crime for any lover of the beautiful to be caught off the sidewalk without a pocket-lens.

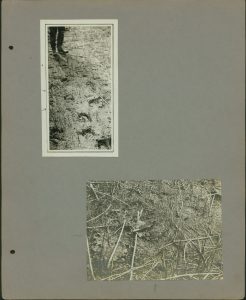

Hackberry Lake View northeast from height south of northwest end

Next we came upon a highly excited group of killdeers. They are always worrying over people, but when they are as crazy and garrulous as on this occasion it means the they have eggs or young — not necessarily in the same township, however, for they go longer distances to borrow trouble than any bird of my acquaintance. We spent some time looking for a nest, and while thus engaged Dr. Wolcott caught sight of a young bird a hundred yards away, on a little cape which ran down among the tules. So we walked in that direction, whereupon the young bird disappeared. Approaching the place where it had been seen, we walked very slowly and examined every inch of the ground, and I had the good fortune to find the youngster, tucked away in a hoof-print in the damp soil near the water. Its back was even with the level of the ground, and its bill was extended flat on the surface, the colors of the bird blending wonderfully with its surroundings. I had started out with only my Kodak [camera], but this was a subject which I wished to photograph with the best lens available, so I hurried back to the ranch, nearly half a mile away, for my camera, while Dr. Wolcott looked about for other young killdeers. Returning on the run, I found my haste entirely unnecessary, for the young bird was precisely as I had left it. The photographing was soon out of the way, and then we experimented with the bird to see how fully it depended upon concealment, or rather protective coloration, for safety. Walking briskly about the bird had no effect. It remained motionless even when touched lightly with straws and with our fingers. Finally I went a few yards away, then turned and walked rapidly back, the last step bringing my foot directly over the bird. Still it remained perfectly quiet; if I had finished that last step I would have finished the killdeer. Then we

picked it up to see if it was really alive, and it was, very much so, and forthwith found its voice, inherited from a long line of vociferous ancestors. When released it ran with surprising speed to the water’s edge, and when we followed took promptly to the water, wading as far as possible and then paddling along almost as expertly as a young duck, until it was finally lost to view among the tules a dozen yards or more from the shore.

During my absence Dr. Wolcott had found three

No caption

11

Young killdeer hiding in hoofprint — same as shown on top of page 9.

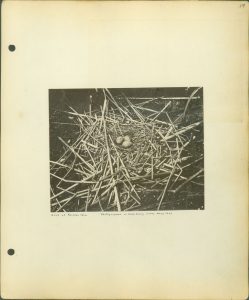

Nest of mallard

more of the young birds, hiding in the scant shelter of dead tules drifted up to high water line — almost the only available concealment on this bare point – and with these we repeated our experiments after taking a couple more photographs. Two of these young birds had closed their wings against their bodies with blades of grass between, so that is appeared to be growing on or through them; this is shown rather unsatisfactorily in one of the photographs on page 9 giving little idea of the perfection of the illusion as we saw it. — Not until actually picked up did they find their voices or their legs. Two of them ran along the shore to a point of safety, while the third, upon being cornered, took to the water and hid among the tules.

It was altogether a very pleasant and interesting experience for us, and fully compensated for the annoyance of being tagged and berated by a committee of grown-up killdeers for the next two hours.

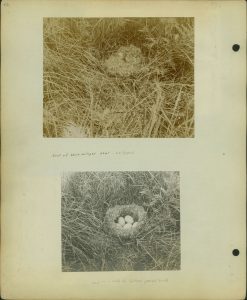

Dr. Wolcott next found a nest of the mallard, with eight eggs, which I photographed. The nest was composed entirely of dead tules, and the eggs rested in a fairly well-cupped structure of this material, about four inches above the surface of the water.

Next a black tern colony was located, far out among the tules in water two feet deep. The nests were on floating masses of vegetation, and contained both young birds and eggs.

Site of mallard’s nest

Nest with young and egg of black tern

The young were beautiful, fluffy little things, and showed little fear of us; but when informed by their frantic relatives overhead that we were a bad lot, they dutifully took to the water and paddled away. We rounded up two of them and placed them in a nest, and with Dr. Wolcott’s assistance I got their photograph. The old birds were very much disturbed, and

swooped down toward us in an endless procession, there being forty and fifty of them, and each

having as many swoops as he wished. They frequently touched us with their wings. Several Forster terns joined in the demonstration, and with their superior mastery of invective almost disheartened us; for in the whole realm of nature I know of no term of scornful, sarcastic vilification which approaches that applied to his disfavorites by the Forster tern.

I regret having no photograph to show the “hiding” of the baby terns, and must resort to the unhappy expedient of a pen sketch. They paddle away from the nest until they find two or three tules in a group; between these they thrust their foolish little heads, with the bill flat on the surface of the water, and behold, they are hidden — ostrich fashion!

Not far from this point, in a very muddy tract near shore, was found a nest of the Virginia rail with seven eggs, and the camera was again brought into action.

Nest of Virginia rail

Two old nests of the same species were found within a few feet of the occupied nest.

On the shore we found an unusually large garter-snake, with very red stripes. The snake was fully 48 inches in length, and had a desperate wound on its side, the probable manner of its infliction affording us a fine field for conjecture — the net result of which, however, was like that of Huckleberry Finn’s prayer: nothing come of it.

While wading about among the tules farther along the lake shore we came upon a family of young mallards, half grown, sufficiently developed to be rapid swimmers but not yet able to fly. They scattered in every direction with much splashing and quacking. I started after one as fast as I could go, and it headed for the reeds near shore, which it reaches many yards ahead of me. A careful search among the grass finally discovered it, and its terror when I took it up was so pitiful that I did not detain it long. Dr. Wolcott came up at this point and I handed him the duckling while I prepared my kodak (sic); then we waded out to clear water — the idea being to get a photograph of the bird as it swam away. Diligent search of these pages, however, will disclose the fact that no photograph corresponding to these data appears. Instead of swimming quietly and gracefully away, as a thankful young duck should have done under these circumstances, it struck out with such vigor and so vast a splashing of water and beating of pinfeathered wings that my 1/100-second snap-shot looks like a time exposure; everything shows motion, even the atmosphere being a little shaky.

It is interesting to observe that here within two hours we had found a young shore-bird taking to the water for safety, and a young water-bird making for the shore with all its might with the same idea.

Killdeer

The white thistle of the Sandhills

On the 16th I hunted up the young killdeers again, finding three of them with little difficulty. On this occasion no amount of crowding would induce the birds to take to the water. I also got two rather inferior photographs of the parent killdeers, which came within ten feet of me while I was holding a young bird in my hands.

Near the lake shore I found a hob-nosed snake, a harmless and useful species which has an indiscreet habit of flattening its body and hissing. This behavior earns for it a bad reputation; it is known in the sandhills as the “spreading adder,” and is greatly feared, and of course killed on sight. There are only four poisonous snakes in the United States: the rattlesnake, generally distributed over the county and embracing many species, all provided with the characteristic rattles; the copperhead and the water moccasin, found in the southeastern part of the country; and the coral snake, confined to the Gulf coast. But all snakes must suffer on account of the bad reputation of the few poisonous species. These little hognosed snakes are really amiable enough on acquaintance, and it is unfortunate that they cannot eliminate their propensity for bluffing. I took a photograph of the one encountered this morning, trail and all. Throughout the sandhills one finds many “snake-tracks,” but few snakes.

I visited Clear Lake, a mile and a half east of Hackberry, at 10 a.m. This lake is more nearly round than most of the others, and conditions along its shores are the reverse of those on Hackberry, the north side being clear of vegetation and the south side grown up with tules. The

Hog-nosed snake

Clear Lake

Clear Lake

On north shore of Hackberry Lake

On north shore of Hackberry Lake

water is strongly alkaline. Generally these lakes are in depressions formed by long, sweeping

slopes from the sandhills, but Clear Lake departs from the ordinary in having a line of steep

sandhills along its north shore. I took a photograph near the northwest “corner” of the lake

showing plant zones, and another farther east where the sand was playing the unusual prank of

moving from south to north in a long tongue. Doubtless this is due to some air current which owes its direction to the shelter of the high north bank.

Dr. Wolcott had gone to Clear Lake earlier than I, and together we dug out of the moist sand large numbers of beetles, chiefly Omophron and Bembidium. The presence of Omophron colonies was indicated by a peculiar roughness of the sand surface which we soon learned to recognize, and we got a fine collection of these beetles. Along the shore we found large numbers of tiger beetles of two species, Cicindela hirticollis and C.

repanda, the latter departing from normal in its unusually large size.

On the morning of the 17th the young killdeer were not to be found, so I sought solace among the beetles and spiders of the lake shore. The photographs on this page show the site of morning’s operations. On the lily-pads I collected numbers of a species of Donacia — — an active, handsome little beetle who behaves like a fly, and who says that in the whole world there is not to be

found so homelike a home as a cool,

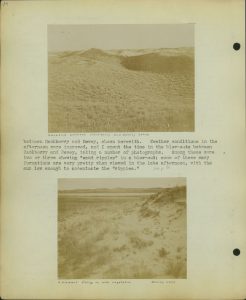

A view in the Sandhills Large blow-out

green lily-pad, suitably placed among the tules and rocked by the gentle motion of the water; in which, other things being equal, I concur. — I photographed again this morning a clump of Muhlenbergia pungens, though I had previously taken two photographs of it at Halsey.

I spent the afternoon in a boat, exploring the tules on the north side of Hackberry Lake, in search of birds’ nests. Coots and mallards had nested freely here, but all the nests were empty. I had a fine visit with the long-billed marsh wrens, which were numerous. I examined fourteen nests — three empty, one with one egg, two with three eggs, five with four eggs, and three with five eggs. I did not want the eggs, of course, but I did want to enjoy the pleasure of looking at them, and the birds were apparently quite willing, singing their hardest while I invaded their homes. These dainty little baskets are works of art, and as I did not photograph taken in the marshes adjoining Cut-off Lake, near Omaha, several years ago.

Nests of the black tern were very common; I noted two with one egg each, eleven with two eggs, and five with three eggs. In view of the presence of young birds in other colonies it seemed probable that these were second nestings, and I had the curiosity to ascertain whether the eggs were fresh, which proved to be the case with the half dozen or more which I tested in water. The abusive Forster terns were again much in evidence, but I found no signs of their nesting, and as the flight of the birds bearing food was invariably to the northeast, I presume their colony is domiciled among the rushes of Trout Lake. Once more I include a photograph of earlier taking, showing a nest of Forester tern photographed on Hackberry Lake in May, 1903.

Most of my discoveries were made, not from the boat, but by wading about among the tules, rowing to desirable points and then taking to the water. One must have amphibious inclinations to accomplish much along these lake shores. I got into some uncanny place during the course of the afternoon. One of these was the nesting site chosen by a small

Nest of forster tern Photographed on Hackberry Lake, May 1903

Nest of Long-billed marsh wren

Nest of Long-billed Marsh Wren

colony of black terns — not over clear water as usual, but in a protected slough among the tules and reeds, where a circular tract twenty yards across appeared to be floating mud, and suggested unhappily a bottomless pit. Stepping into this mass, the surface offered a soggy resistance, which under added weight suddenly broke through, reasonably firm footing being found eighteen inches or two feet below. The origin of this peculiar tract was doubtless dude to the decay of vegetation and its ascent to the surface with a mass of the bottom mud, which on account of the protection of the reeds was not affected by the waves. In this ridiculous place the aesthetic terns had seen fit to establish their home, and several nests were scattered about the surface — a few wisps of vegetation thrown together, and

an alleged depression shaped by the birds in the center. The range of nesting artistry among birds

is almost as “varied as human conduct,” and as hard to reduce to a coherent system.

One peculiar freak of the lesser yellowlegs, observed during this afternoon and on other occasions, deserves mention. These birds ordinarily confine their operations to shallows along the water’s edge, as befits “shore-birds”; but here they are very fond of running

about on the lake vegetation, which forms mats on the surface in many places, outside of the fringe

of tules. It is not uncommon to see dozens of them feeding on these areas. On one occasion today,

while laboriously forcing one of these tracts, I came upon a party of these birds, and they

manifested a great interest in the disturbed area over which the boat had passed, as each tug at the oars had left a mass of vegetation projecting above the water. This meant to the birds a more available food supply than usual, and it was interesting to see them hurry in to take advantage of it. Doubtless the nearer ones actually saw struggling insects or crustaceans in the masses and went after them, and the more distant birds moved on account of the action of their fellows rather than on account of any deep reasoning. But whether this be true or no, it is certain that birds a hundred yards away came with almost undignified haste to the scene of activity. I could not get near enough group, as the boat in these surroundings was unwieldy as a battleship; but I photographed a single bird wading about on this vegetation.

The morning of the 18th was cool and breezy, the wind being in the southwest and weather alternating between sunshine and showers in surprisingly rapid succession. It had rained rather sharply

Black tern’s nests

during the night. I spent the greater part of the morning collecting beetles and spiders along the lake shore, and as the afternoon was more settled, Dr. Wolcott and I took a trip around Hackberry.

I photographed a ruined sod-house near north shore of the lake, its lines suggested such utter lonesomeness and desolation. Sod—houses are much used here, for obvious reasons, and some of the wealthiest ranchers live in them; but I can not help feeling that, wealthy though they be in cattle and collateral, they must be poverty-stricken in imagination and sensibility. If I were condemned for my crimes to live in this region I would build me a mansion of boards, even if I had to go without corn-meal; for I like not these sod sepulchers.*

But a frame house is not necessarily a home. While still ruminating over the sadness of soddies, I came upon a frame shack—one of the two “buildings” on this side of the lake — and as the door was boarded up I looked in at the in at the window, having mislaid my manners. It is difficult to describe that interior, for everything impinged violently upon the senses at once. A bed was in the corner, with tattered, moth-eaten bedding, upon which were piled ragged clothing, yellow breakfast-food boxes, a jug, some lumber, minor implements and tools, and stacks of papers and magazines (bespeaking a litterary character?). Long pine boards were thrust diagonally here and there from floor to ceiling according to their dimensions, presenting the aspect of a game of jackstraws on heroic lines. The floor was covered with everything but carpet; the corners were pyramids of possessions. Such systematic chaos never before met my eyes. Nothing about the place

suggested that woman had ever entered it, which is certainly a piece of unbelievably good fortune

for some woman. — All of which would not have been mentioned except for the yellow-headed blackbird. He was in the middle of all this rubbish, hopping about quite optimistically. I could not imagine how he had entered the place, but as it seemed unlikely that he could find his way out I walked around the corner of the house with an idea of breaking and entering. I reached the other side just in time to see him come out of a small opening near the floor and fly away. From the fact that the blackbird had sought this means of exit and made his escape during the few seconds which passed while I walked a distance of less than ten yards, it was very plain that the bird knew the premises well; this accuracy and effectiveness of conduct was not first performance. It would be interesting to know how often he visited the place, and his opinion of humanity.

Considerable numbers of yellow-headed and red-winged blackbirds were found about Hackberry, and observations in previous years indicated that they nested there in large colonies. It was

therefore interesting to us to note that in all our present investigations about this lake we

had not until today come upon any nests of either species. In a limited

Black tern’s nests

[handdrawn image of birge net]

area today I found two or three “1911 models” of each species, no other such nests coming under our observation on Hackberry. The nesting areas there are ideal, and it is a peculiar circumstance that they had this year almost deserted this lake as a nesting place.

I took a photograph today of Dr. Wolcott using the “Birge net,” a device for collecting plankton — “plankton” being the term applied to “pelagic animals collectively: distinguished from coast or bottom forms.” The Birge net, named after its inventor, looks like this:

The cone is made of galvanized iron netting, attached to a bag of silk, and to the end of this fitted a screw cap. A heavy cord is attached to a ring in the end of the cone. The whole is heavy enough that it may be

thrown a distance of 50 or 75 feet. It is generally used in shallow water filled with vegetation, and after being thrown out is drawn rapidly through the water, the wire netting excluding large objects and admitting the small animals — water-mites, crustaceans, the lesser beetles, etc. The water escapes through the silk net and after several casts have been made the screw cap is removed and the “collection” washed out into a bottle, and preserved in a weak solution of formalin.

We devoted some attention to the butterflies at the boggy northwest end of the lake, then passed on to the south side. The hills here are abrupt, but removed several hundred feet from the lake shore, and thickets of plum and hackberry trees are scattered about the slopes. Chats and kingbirds were noted here.

Dr. Wolcott using his Birge net, Hackberry Lake

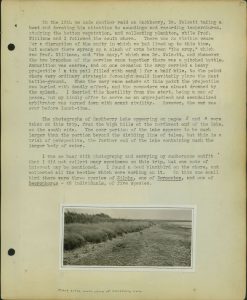

On the 19th we made another raid on Hackberry, Dr. Wolcott taking a boat and devoting his attention to soundings and recording temperatures, studying the bottom vegetation,

and collecting plankton, while Prof. Williams and I followed the south shore. There was no visible cause for a disruption of the amity in which we had lived up to this time, but somehow there sprang up a clash of arms between “the army,” which was Prof. Williams, and “the navy,” which was Dr. Wolcott, and whenever the two branches of the service came together there was pitched battle. Ammunition was scarce, and on one occasion the army carried a heavy projectile (a tin pail filled with sand) for a half mile, to the point where very ordinary strategic foresight would inevitably place the next battle-ground. When the navy came ashore at this point the projectile was hurled with deadly effect, and the commodore was almost drowned by the splash. I decried this hostility from the start, being a man of peace, but kindly offer to serve as an unprejudiced and scandalized arbitrator was turned down with scant civility. However, the war was over before lunch-time.

The photographs of Hackberry Lake appearing on pages 5 and 8 were taken on this trip, from the high hills at the northwest end of the lake, on the south side. The near portion of the lake appears to be much larger than the portion beyond the dividing line of tules, but this is a trick of perspective, the

farther end of the lake containing much the larger body of water.

I was so busy with photography and carrying my cumbersome outfit that I did not collect many

specimens on this trip, but one note of interest may be mentioned. I found a dead blackbird on

the shore, and collected all the beetles which working on it. On this one small bird there were

three species of Silpha, one of Dermestes, and one of Necrophorus, — 48

individuals, of five species.

Plant zones, north shore of Hackberry Lake

Atypical blowout east end of Clear Lake

On the 20th Dr. Wolcott and I followed the north side of Clear Lake, collecting Omophron, Bembidium, and among our favorites (the tiger beetles), Cicindela hirticollis, repanda, punctulata, and limbata. We were interested to see numbers of Omophron, usually nocturnal, moving about in the bright sunlight. There must be tens of thousands in this colony, and as our collecting in this genus heretofore has been limited to scattered individuals, we were inclined to take large numbers.

We had a fine view of the perculiar “revolving” habit of the Wilson phalarope. With the lack of visible reason which affords one of the charms of field study, these beautiful birds, in groups on the water, revolve rapidly for minutes at a time, each holding his place in the group and simply whirling about for the love of it, some from the right to left, others from left to right, until it makes a mere mortal dizzy to watch them.

Ring-billed gulls are fairly common about Clear Lake, and we enjoyed seeing many of these

handsome birds.

I found a large spider—a lycosid—in a rather peculiar position, affording another nice problem for conjecture. It had climbed up several stalks of a tall, flexible grass (Redfieldia) to a point eight inches above the sand, where it held together an “armful” of the stalks. It did not appear to be waiting for anybody, and was simply hanging on, swaying in the breeze. There was no tunnel in the vicinity.

North shore of Clear Lake

We returned at noon to the west end of the lake, and after lunch started out along the south

shore, which was comparatively uninteresting, though we did have a lot of fun with a family of

young mallards; we caught four and put them in my butterfly net, and what a squirming mess they

were! These birds were younger than those we had seen on Hackberry, but quite as vociferous and

terrified. I tried to photograph them as they were released, as I had tried before on Hackberry; but the instant they touched the water they disappeared under the surface. We also flushed several conveys of young sharp-tailed grouse, which was fine sport. When the first bird from a covey rose from the ground we usually stopped in our tracks to see if we could discover others in the grass, but they were never visible, though the next step forward might startle two or three from the very tufts

we had scanned most closely.

Rounding the east end of the lake, we followed the north shore back, finding some interesting blow-outs and taking several photographs. When we reached “home” we were about fagged, and Tobe’s — but I haven’t said a word about Tobe.

On the afternoon of the 21st I took a trip alone over the sandhills north of Hackberry and southeast of Watt’s Lake, to photography some blow-outs I had seen, and to collect Cincindela limbata. This is a very interesting

tiger beetle. It was first described by Thomas Say, who went as naturalist on Long’s expedition

in 1819. [Major Stephen H. Long, Expedition 1819-1820] According to his published description

of the species (1823), it was “found on the Nebreska (Platte) and Arkansa Rivers,”

without any

more definite information as to its distribution and nothing regarding its habits.

The

“Nebreska” is quite a stream, and for about sixty years C.

limbata was not found;

view north across east end of Clear Lake [photograph no longer pasted in narrative,

only caption remains]

An unusually bare blowout [photograph no longer pasted in narrative, only caption

remains]

30

Habitat of Cicindela limbata

a bare tract in a blow-out

31

Sand erosion — south wall of blow-out

32

then it was rediscovered in the Nebraska sandhills by a surveyor, Mr. E. P. Austin, who had

natural history tendencies. The species is closely restricted to the blow-outs —

generally to active ones, where the vegetation is scanty and the expanse of sand large

and

shifting; and I found them numerous in these places today. I collected about thirty

specimens,

but unfortunately these, and most of the others collected during our sojourn in the

sandhills,

were subject to a loss of about 80% by reason of discoloration. In species of tiger

beetles where the pigmentation of the elytra be fully “chitinized,” or hardened; but

in these

beetles and others where the wing-covers are white, unless the chitin be fully developed

and

the wing-covers hard, discoloration is almost certain to occur after the specimen

is dried

— ugly brown blotches appearing, or the oils from the body modifying the clear white

or cream color of the wing-covers until they are translucent or dead gray and the

specimen

ruined.

Out of probably 200 specimens taken during the summer, I released perhaps 75 on account

of

soft wing-covers, and of the remaining number it is not likely that more than 30 or

40 are in

good condition. — This species is remarkable also for a peculiar freak of

distribution, being found in this region and then again in Manitoba.

July 22nd was spent with Dr. Wolcott in a trip northeast over the sandhills, past Monahan’s

Lake, and to Trout Lake. Here we were disappointed in finding no boat available, and our

observations were confined to shore. The one notable event of the trip was the discovery

of a

nest of the blue-winged teal with eight eggs. It was a beautiful structure; a very slight

depression had been formed in the ground in a dry situation among the grass, 200 yards

from the

lake; this depression was lined with grasses, and on this layer the cream-colored

eggs were

placed. The entire body of the nest above the grass foundation was formed

33

of down from the parent bird, and was a fluffy mass three or four inches high. We

had come

out of a growth of low bushes immediately upon the nesting site, and the nest was

discovered to

us by a the flight of the mother bird. Subsequent notes and photographs appear under

date July

25th.

We collected an interesting lot of leaf-eating beetles on the willows near Trout Lake, but

here again the unfortunate combination of unhardened wing-covers on a light-colored

beetle

robbed us of most of our specimens. Even so negligible a person as a beetle-collector

has his

troubles.

Two families of short-billed marsh wrens were observed among the willows here, and I was glad

to get acquainted with this species.

We found four specimens of a plain-winged yellowish butterfly — a “skipper”

— which Dr. Wolcott did not recognize. It is probably new to the state list.

Returning to the shortly after noon, we spent the rest of the day on Hackberry Lake. A

violent electrical storm passed near us in the evening, from northwest to southwest,

and we got

only its extreme southern edge — which was enough.

The botanists killed a rattlesnake today, in the sandhills less than half a mile from

the

ranch. They collected the seven rattles, and I preserved the skin, which is a beautiful

thing,

with fine mottling. The snake was about 40 inches long.

July 23rd was very chilly, with a strong wind from the northwest which had persisted

all

night. It bought disaster to our hydrograph, which Dr. Wolcott had placed in a boat 300 yards

from shore to record the bottom temperature. The boat if anchored at one end only

would have

ridden through the storm, but to keep the delicate tube which leads to the bottom

from mixing

up with the anchor chain it was necessary to anchor both ends. So when the wind came

up, the

side of the boat was exposed, and the dashing waves soon filled it. In the morning

the gunwale

was barely visible above the surface with the aid of a binocular, and Dr. Wolcott had a hard

fight against the wind and waves to reach it. In spite of the soaking, the record

was legible,

and the instrument was not injured.

I took a rather uneventful trip in the afternoon to Clear Lake, along the north side of

Dewey, and back by the south shore of Hackberry, just to fill in the time, for the weather was

not fit for photography or collecting of fishing.

On July 24th the wind was still violent, and I took a trip alone over the sandhills

to the

southeast, taking two photographs — one of Hackberry Lake from the southeast (see

page 6), and another of the sandhills

View north across Trout Lake [photograph no longer pasted in narrative, only caption

remains]

Sandhills between Hackberry and Dewey Lakes

34

between Hackberry and Dewey, shown herewith. Weather conditions in the afternoon were

improved, and I spent the time in the blow-outs between Hackberry and Dewey, taking a number of

photographs. Among these were two or three showing “sand ripples” in a blow-out; some

of these

wavy formations are very pretty when viewed in the late afternoon, with the sun low

enough to

accentuate the “ripples.”

A blowout filling in with vegetation Dewey Lake

Sand slides in sheltered angle of blow-out

37

Yucca

38

Yucca

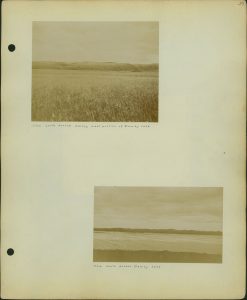

View south across marshy west portion of Dewey Lake

39

View south across Dewey Lake

40

Sennett nighthawk

Nesting site of blue-winged teal, west end of Trout Lake

41

On July 25th Dr. Wolcott and I again visited Trout Lake, to see how our blue-winged teal was

faring. We had the nesting site carefully located, and approached it from the clear

region

south, instead of through the bushes north of it as before. When we reached the vicinity

the

bird flew from a point fifty or sixty feet from the nest, and on approaching it we

found that

she had discovered our presence, having carefully concealed the eggs by drawing the

mass of

soft down over them. I photographed the nest exactly as she had left it, and again

after

pressing back the downy sides to their normal position.

We left Stilwel’s

ranch on the morning of the 26th. Passing Dad’s Lake, which I had not

found opportunity to visit during our tarry here, we stopped long enough to photograph

the

eared grebe colony, from the shore, with a cloud of black terns hovering overhead, and the

photograph, such as it is, appears herewith.* This was one of a number negatives

which fared badly in development at the Forest Reserve Station

, on account of high

temperature.

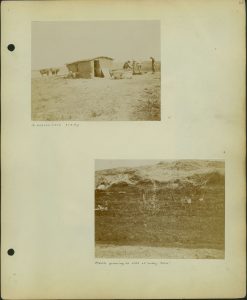

Our route to Thedford was the same as the followed when we came. During one of our stops to

change horsesese , several miles south of Brownlee, I took two photographs — one of a

“convenience” soddy with the corners worn off by cattle, and another of the north

side of a sod

“barn” with various plants growing insistently from its sides.

negative.

Nest of blue-winged teal — as found

42

and — — with the feathers pressed back

43

A convenience soddy

43

Plants growing on side of soddy “barn”

44

Grama grass

45

We reached Thedford in the early evening of the 26th, and before we left the next morning I

took one more photograph, again with a soddy as the subject, this one showing a fine

cluster of

prickly pear of growing on the roof.

Soddy at Thedford

46

47

And now, A Dissertation upon ye Gentle Arte of ye Taking of ye Blacke Basse for Foode

& Sporte. We spent an hour or so almost every evening on Hackberry Lake, as a

comfortable and profitable ending of the day. There were plenty of boats, and though

they were

chiefly wrecks we made them serve, having acquired a fine disregard (I speak for myself

alone

in this) for wet feet.

Hackberry Lake is literally crowded with black bass, of the “small mouthed” species. It has

been stocked from time to time, and conditions have been favorable to the growth of

great

numbers of the fish. Their behavior indicates, however, that the cost of living is

a desperate

problem; they come up to the very shore line in search of food, a walk of a few rods

along the

shore at almost any point disclosing dozens and sometimes hundreds as they dash for

deeper

water. During the early evening there is usually a period of an hour or two when they

jump

clear of the water by scores, chiefly among the tules or above the “moss,” but in

clear water

as well. When they are moving thus actively they strike freely, and this was our time

for

fishing. There are no minnows in the lake; a minnow in Hackberry would not last long

enough to

sink. Few of the fish are large; the best fish we caught weighed about a pound and

a half; but

on the other hand, the smaller fish are rarely caught, and one might reasonable depend

on

catching his lawful 25 fish under favorable conditions if he knew how to choose his

fishing

tools. And 25 black bass weighing from three-quarters of a pound to one pound each

are tidy

lot. A few larger fish were found dead on the south shore of the lake, some of them

having

weighed probably as much as 2-1/2/ pounds.

There is a great deal of talk about the influences of the wind, the south wind being

considered the most desirable on Hackberry, doubtless because it is the hardest to raise. I did

not find that the difference was profound. On the few occasions when they would not

strike, the

wind was as often of the prescribed tone as otherwise.

The bait generally used here is the “Dowagiac minnow,” a gaudy wooden thing bristling

with

clusters of hooks. This is preferably used with a casting-rod, being thrown a distance

of 50 or

75 feet and reeled in with moderate speed. In the absence of a casting-rod it may

be used with

a long cane pole and a tied line, though the reel is preferable. Everyone swears by

the

Dowagiac — or the “draw-jack,” as it is barbarously called, the geographical

significance of the name being entirely lost upon the average fisherman. I tried the

Dowagiaz

for a grand total of fifteen minutes, the total being the only grand feature of the

trial. It

is like fishing with a flat-iron; splash it goes on the surface, like a dead duck,

and then

follows the joy of reeling in, when some of the twenty hooks almost certainly need

clearing of

vegetation before another cast — for the best fishing is among the tules or

“moss-beds.”

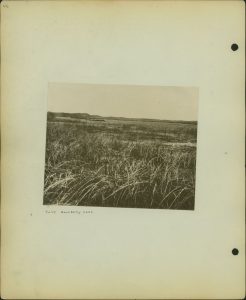

Tules, Hackberry Lake

48

Various spoons, spinners, floating baits, artificial minnows, etc., have their devotees,

and

all are probably good for something somewhere else, though their attractiveness to

the

Hackberry bass seemed limited, judging by the sorry strings brought in. Grasshoppers

were the

favorite live bait, and were readily taken

by the fish, though not so readily taken by the fisherman. The only available species

of

grasshopper is the big gray or brown fellow with yellow and black flight—wings. Their

power of vision is great, and their ability in flight is admirable or execrable, according

to

one’s point of view. They must be taken with nets, and it is not uncommon to chase

one for four

hundred yards before (or without) getting within striking distance. On lucky days

one may get a

dozen in a half-hour; onlucky days it is different. The big “lubber” grasshopper is also good bait, but was not

present in sufficient numbers to be dependable. Lizard tails are used to some extent,

but for

my part I like the lizards too well to heap this indignity upon them. Frogs serve

very well,

but are hard to find. Fat pork us used more or less, and is such good bait and so

easily

procured that its limited use is hard to understand.

Now I rise to remark, with all the arrogance possible, that I was It in the matter

of fishing

on Hackberry Lake. My outfit was unorthodox and my choice of bait childish, but I got the fish.

I used my light trout rod, eight feet long to start with but decreasing gradually

though the

season until my final base were caught with what was left of the tip, the rod proper

and the

reel being abandoned and the line manipulated with my fingers. The rod was shaky and

senile,

and I simply wore it out on is in very bad taste, but I glory in it, for so also were

in bad

taste the early pity and later criticism and abuse which I bore because of my convictions

and

my luck.

It was an heretical thing to have done, but I had smuggled in four bass-flies —

little bunches of feathers of the guinea-hen, tied to a hook of moderate size and

fitted with

gut snells. [short line of horsehair, gut, extended fishing line in fly fishing] From

a boat it

was easy to whip alternately from side to side with as much as 40 or even 50 feet

of line, so

the area “fished” was considerable, while the outfit was so light that the casting

did not tire

the arm. When the bass were striking at all they would take this fly, though as it

became dark

in the evening I generally stuck a small piece of fat pork on the hook, which the

fish could

see much better; they would strike at the fly just as ravenously in the uncertain

light, but

inaccurately, and the white bit on the hook gave them a better target. I fished sometimes

as

late as nine o’clock with this combination, and the darkness seemed to make little

difference.

49

Occasionally I found it necessary to go over my fish and release the smaller ones

so that I

might go on fishing and not exceed the lawful limit of 25; for I confess to a weak

and foolish

observance of the game laws, in which I am a lonely figure.

The boat I used was fitted with a chain attached to the anchor, instead of a rope,

and no

such thing as silence was possible in changing position. But the noise made no difference

to

these bass; after the rattlety-bang of casting anchor, it was not uncommon to get

a strike

within a minute or two. And when here on our second trip this season, after September

1st, when

the game season was open, I on one occasion took a long and unsuccessful shot at some

passing

mallards, resuming my fishing with interest to see how soon the fish would come back after

the

explosion. It was certainly well within sixty seconds when I got my next strike, and

good

fishing continued uninterrupted.

It would be interesting to know just what influence controls the actions and appetites

of

these Hackberry bass. Ordinarily in the early evenings they indulged in a great amount

of

jumping out of the water, and while they were jumping the fishing was generally good.

But on

some occasions these antics would suddenly cease; not a bass would appear above the

surface,

and it was rare to get a strike when these conditions developed.

One other available food fish of these lakes is the blue-gilled sun-fish. These sun-fish

weight from a half to three-quarters of a pound, and are not in the slightest degree

inferior

to the lordly black bass himself in the matter of edibility. When I visited this region

in 1903

they were most common in Dewey Lake, but now they are found chiefly in Watts’ lake. They have

not of late years been numerous in Hackberry Lake. It was a distinct surprise to have them on

two occasions strike at my bass-fly, and put up such a good fight that I did not question

their

being black bass until I got them into the boat.

Large bull—heads are common in Hackberry, and may be seen in the clear water almost

any day; but no amount of coaxing could induce them to take any kind of bait which

suggested

itself to us. So we decided that if they felt that way about it we would try to get

along with

black bass.

50

51

Two parties of fishermen came to the ranch during our visit. The first crowd, “business”

men

from somewhere up north, came in automobiles, which balked in the sand and had to

be pushed and

coaxed along with much swearing. We noted their approach when they were still two

miles away,

and throughout their visit they could generally be heard for about that distance.

They were

boisterous rowdies, and we did not them or their choice of expressions. So when, a

day or two

later, another party came, three in number, and we learned that they were respectively

a

saloonkeeper, his bar-tender, and an Italian pal, from a large city not far from Council

Bluffs, we concluded that our lines had fallen in unholy places, and we were much

displeased.

But that is the funny refreshing thing about people; you never can tell. While their

credentials did not appeal to us, their behavior and their geniality did, and within

twenty-four hours we were hobnobbing quite cheerfully with these people. They had

come out to

fish, and to have a good, wholesome time in the open, and their conduct was in marked

contrast

to that of the supposedly reputable people with the automobiles. Of course they had

liquid

refreshment along, in abundance; but it was beer, and they were accustomed to it,

and never was

there the slightest indication that they had taken too much. And how they did fish!

—

early and late, and between times; their one aim being to take back a creditable lot.

Unfortunately, their luck was not good; in spite of the fact that they fished almost

all the

time their “live-box” out in the lake filled very slowly. So I got in the habit of

adding my

surplus to their box, for Dr. Wolcott and I caught more than we needed for the table. When they

departed, nearly half of their 140 fish were of my taking. This conduct on my part

was very

popular with them, and what I might have done to their beer after they had given me

carte

blanche is measurable only by what it would have done to me. My needs in that direction,

however, were limited; and while I do not propose to compromise any other member of

our

extremely temperate and well-behaved party, I am frank to state that on two or three

occasions,

when I came back from the hot blow-outs, with my tongue parched and my soul burning

in advance

of the theologically appointed time, I found an iced half-pint bottle of amber tonic

the most

comforting thing in Cherry County.

One sad memory lingers. When Tobe the saloon-keeper, fighting with a bass early one

morning,

lost his two-hundred-pound balance and splashed merrily into five feet of water, why,

oh why

was I not there with my camera! I am not given to photographing people on account

of the

superior interest of animals and things; but this subject would have appealed up over

the’ bar

and show th’ fellers when they ranged up on th’ firin’ line, it would be bully, wouldn’t

it? My

suggestion of a repetition was turned down after consideration.

Tobe and Louie and the Dago; they linger pleasantly in my memory — Tobe on account

of his big heart and body, Louie on account of his loyalty to his “boss,” and the

Dago on

account of his boyish delight over the new

Phaca longifolia

52

experiences of the passing days. The latter is quite a man of affairs — a

commission merchant, a banker, an agent for an Atlantic steamship line. Never before

had he

bestridden a horse, and part of his fun was found in going after the cows, from which

expeditions he would return with enthusiasm and sore legs, generally with a story

of his

thrilling adventures. He declared himself very much pleased with the “horse-riding;”

he should

like to have horse—riding every day, and maybe perhaps he might get him a horse when

he came home; who knows?

As a matter of psychological interest only, and not with the least intent of reflecting

upon

our whilom chums from other walks of life, I may state that they never took kindly

to our

snakes. When my hog-nosed snake ran amuck one night and I had to fish him out from

under my bed

and tie him up, Tobe and Louie and the Dago were sleeping the glorious but stertorous

sleep of tired fishermen, and knew naught of it; and when I mentioned

after the great danger had passed — Tobe grew faint and pale and had to open another

bottle!

Blowouts near Hackberry Lake

53

A little “holding” on the shore of Dewey Lake

A wasp of the genus Bembex attempting to dig hole in yielding sand of blow-out.

54

55

The photographs on pages 2 and 3, of waterfalls on Schlegel’s [sic] Creek, a few miles south of

Valentine, were taken during the trip which Dr. Wolcott and I made to this region in latter May

and early June of 1903. The scale of these pictures is not clearly determinable, so

I add this

note to state that the fall of water in the picture shown was respectively about four

and six

feet.

On page 9, in the upper photograph showing the hiding of the young killdeer, it would perhaps

have been better to have eliminated Dr. Wolcott’s legs, as they are not essential to the

composition; but as they look very funny in the “waders,” and as I am almost sure

it will annoy

him to find them here of record, I can not deny myself the pleasure.

The example of sand erosion shown at the foot of page 31 is unusually well defined.

The

photograph shows the south wall of a blow-out, which is about 10 feet high.

Sand in sheltered places in blow-outs is frequently unstable, as shown in the photograph

at

the top of page 37. Any slight disturbance, such as the swaying of a grass-tip or

rootlet, or

the hasty travels of a lizard, loosens the particles of sand starts a miniature avalanche.

The Sennett Nighthawk shown on page 40 was rather a chary subject, and it was only after a

long and cautious pursuit that I succeeded in getting within the desired 15-foot distance.

Throughout this region the meadowlarks and nighthawks particularly, but many other birds as

well, are surprisingly tame, especially if they be approached with a team; it is not

unusual to

pass within six feet of the birds without disturbing them, and I have frequently heard

the

meadowlark in full song when the team was passing rapidly, and well within the distance

named.

Bouteloua hirsuta shown on page 44, is one of the

characteristic sandhills grasses.

On page 50 appears a photograph of a specimen of Phaca

longifolia, a beautiful little plant found commonly in the blow-outs. The seed-pod is

its attractive feature; it is a light green color, about an inch in length, and covered

with

purple blotches. The plant is at its best in May and early June, so we found only

scattered

specimens in July.

A detailed explanation of the photographs on page 54 is very much in order. There

is a wasp

(Bembex sp.) In the sandhills region which

is particularly fond of blow-outs or other bare sand expanses, and several of their

burrows may

be found in almost any such place. They are pugnacious to the last degree, but as

a rule their

misconduct is limited to high-voiced threats of what they have in mind to do to invaders.

This

is an ill-mannerly

56

way to treat visitors, and many were the slain left along our trail. — While

visiting one of the blow-outs near Hackberry Lake one afternoon I found one of these wasps

which had chosen as a site for her prospective home a yielding slope of sand, and

she was

digging away at a terrific rate, though not making the slightest headway — for the

loose sand slid down in a constant stream as rapidly as she removed it. Occasionally

she

stopped to abuse a neighbor, or to buzz significantly about my ears. For three feet

above the

point of attempted excavation and for an equal distance below, the sand was sliding;

and still

the wasp persisted. I spent a half hour watching her, and had much curiosity to know

the final

result, but I did not visit that particular blow-out again.

57

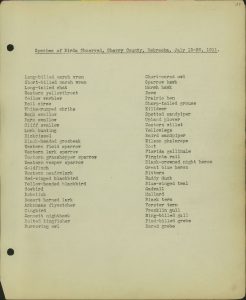

Species of Birds Observed, Cherry County, Nebraska, July 13-26,

1911.

| Long- billed marsh wren | Short-eared owl |

| Short-billed marsh wren | Sparrow hawk |

| Long-tailed chat | Marsh hawk |

| Western yellowthroat | Dove |

| Yellow warbler | Prairie hen |

| Bell vireo | Sharp-tailed gross |

| White-rumped shrike | Killdeer |

| Bank swallow | Spotted sandpiper |

| Barn swallow | Upland plover |

| Cliff swallow | Western willet |

| Lark bunting | Yellowlegs |

| Dickcissel | Baird sandpiper |

| Black-headed grosbeak | Wilson phalarope |

| Western field sparrow | Coot |

| Western lark sparrow | Florida gallinule |

| Western grasshopper sparrow | Virginia rail |

| Western vesper sparrow | Black-crowned night heron |

| Goldfinch | Great blue heron |

| Western meadowlark | Bittern |

| Red-winged blackbird | Ruddy duck |

| Yellow-headed blackbird | Blue-winged teal |

| Cowbird | Gadwall |

| Bobolink | Mallard |

| Desert horned lark | Black tern |

| Arkansas flycatcher | Forster tern |

| Kingbird | Franklin gull |

| Sennett nighthawk | Ring-billed gull |

| Belted kingfisher | Pied-billed grebe |

| Purrowing owl | Eared grebe |

58

Species of Butterflies Observed, Cherry County, Nebraska, July 13-26,

1911.

- Anosia plexippus. Very common.

- Euptoieta claudia. Common everywhere.

- Argynnis idalia. Fairly common.

- ” cybele. In swampy places about Hackberry Lake.

- ” bellona. One specimen, west end of Clear Lake.

- Phyciodes tharos. Common on low ground.

- Pyrameis cardui. Common everywhere.

- ” atalanta. Common on low ground.

- Junonia coenia. One specimen, Clear Lake; one specimen, Hackberry Lake.

- Satyrus nephele. Abundant.

- Pararge canthus. Common about wet meadows in vicinity of lakes.

- Lycaena melissa. Common everywhere, fresh specimens.

- ” comyntas. Few specimens, and those badly worn.

- Chrysophanus hypophloeas. Common about shores of lakes.

- ” thoe. Few specimens; found in same places.

- ” dione. One specimen, shore of Clear Lake.

- ” helloideas. Abundant near Trout Lake; also found elsewhere.

- Thecla titus. Not common.

- Colias eurytheme. Abundant.

- ” philodice. Abundant.

- Nathalis iole. Along shores of lakes.

- Pieris protodice. Abundant.

- Pholisora catullus. Common.

- Pyrgus montivaga. Common.

- Pamphila peckikus. Common on low ground.

- ” cernes. Common about shores of lakes.

- ” vitellius. Shores of lakes; not common.

- ” ? Found occasionally in hills. (New species?)

- ” dion. West end of Hackberry Lake.