Great Nebraska

Naturalists and ScientistsFrank H. Shoemaker

“Cut Off Lake”

left to right

F.H.S.

Dr. R.H. Wolcott

I.S. Trostler

Cut-off Lake, July 4, 1902

| 1901 | Transcript | Omaha area | |

| July 21 |

Trostler and I delayed starting on our planned Cut-off Lake expedition until 2 p m, with the idea of escaping what we considered as presumably

the hottest part of the day. Among the willows, which arrest all air movement, the

heat is excessive. It was entertaining to find later, by the Omaha weather report, that at 4:30 p m, after we had already sweltered for about two hours,

the temperature had reached its maximum for the day: 105 degrees. In places not shaded,

where the water was eight inches or less in depth, it was unpleasantly hot to our

ankles and shins, by reason of continuous action of the sun upon still water; there

being in these “cut-offs” from the Missouri River no appreciable current, except of

couse in periods of river rise.

Our first visit was to the least bittern’s nest in the reeds which we had photographed with eggs during the last days of June.

The nest was empty, and in a moment we might have gone on, but one of us chanced to

see a young bittern squatting in sparse sedge, pretty well concealed, his neck rigid

and his bill straight up. As we went nearer his effort to be inconspicuous was abandoned,

and he understook instead to terrify us by sweeping strokes of his long neck in our

direction. A moment of this, and his nerve failed; away he scrambled through the reeds,

with surprising for speed for so young a bird.

I went in pursuit and caught the bird; and shortly afterward we located and caught

another. There had been four eggs in the nest, so we looked carefully for two more

young birds, without success, so with

July 21 — continued

the two grotesque little creatures we prepared to take some photographs. I found a

straight dead willow about feive feet long and thrust its butt into the mud, with

a slope of about 45 degrees. Trostler placed his tripod firmly and focused on the

sloping stick; then I ventured to perch the young birds upon it.

I had regretted our finding only two of the four young birds; but long before we had

finished exposure of the nine plates devoted to this most attractive subject, I realized

fully that two birds were enough; indeed, at the time I thought two birds were a pair

too many. Time after time I had to pursue them through the reeds, with hot water to

my knees; it must have been ten minutes before they were sufficiently quiescent to

perch. I fear that their seeming quiet was the beginning of fatigue, but even as they

finally perched, their attitude and their actions were warlike.

When Trostler and I go together, as happens frequently and none too often, we divide the labor,

when our bird subjects are restless. He adjusts the tripod, does the focusing, and

makes all exposures. We both use 5×7 cameras with 5×7 plates. He takes his personal

pictures with his camera; then places my camera on his tripod and takes my pictures.

On occasion he uses his camera for both sets of picutes, using my plate-holders for

mine, as they fit both cameras. — He is kind enough to proclaim a fancy that I get

along with the restless birds better than he can; and it is a definite fact that he

is fare more skilful [sic] and expeditious than I in handling the camera; so our team

work is good.

July 21 — continued

So our picture-taking began. It was slow work, for one or both birds would occasionally

jump into the reeds and scamper away, with plenty of speed, and had to be recaptured.

I arranged a makeshift shade by tying willow tops together, in wich we gave the birds

frequent respite. — Most of the nine plates exposed were spoiled by sudden thrusts

of their necks; but we got some good photographs. It was well worth the hot, muddy

effort, merely to see these odd young things and to study their behavior; and to bring

away satisfactory pictures, to convey to others a part of the story, made the rather

hectic endeavor not only a success, but in retrospect, a definite pleasure.

Despite the fact that it may have been done in earlier notes, I shall define here

the two types of nests which are built by the least bittern.

The first type is built always above still water, among reeds, tules, or sedges. It

is more definitely cupped, though still flat, then nests of the second type. It is

constructed entirely of short and some long pieces of dead tules, sometimes with flat

dry reeds included. It is placed just above water level, as is also the habit of the

coots, gallinubes, and rails. Its situation lowin masses of the plants named above

affords excellent concealment.

The second type, almost always above water, is a tree nest, in more open placement,

with no pretense of concealment. Here it is invariably in willows, at height varying

from three to a maximum of

July 21 — continued

eight feet. It is a flat structure like that of the herons, sometimes slightly cupped, and is built entirely of small dead twigs, occasionally

but not often with reeds as a sparse lining.

The two types are about equal in number in this area. It is interesting to speculate

with reference to the variant habits of nesting in a clearly defined species; but

my experience after having examined approximately a hundred nests of each type have

resulted in no conclusions.

The species of tule found here is Scirpus fluviatilis (Torr.) A. Gray. It grows in shallow water, gaining in its mature state a height

of three to six feet; a simple, cylindrical, leafless, blue-green, pithy stem, the

flowering not conspicuous. Strange to say, its accepted common name is bulrush; through

by hunters and others with intimate though not scientific knowledge of plants, a growth

of these is always called a tule swamp; they sensing, as do I, a rush as a flat-leaved, coarse, grass-like plant.

Photographs of the least bitterns, its nests, eggs, and young. All taken in Cut-off Lake, bordering the Missouri River northeast of Omaha, Nebraska.

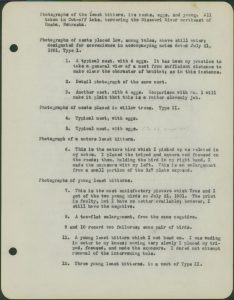

Photographs of nests placed low, among tules, above still water, designated for convenience

in accompanying notes dated July 21, 1901, Type I

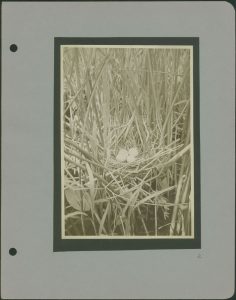

- 1. A typical nest, with 4 eggs. It has been my practice to take a general view of

a nest from sufficient distance to make clear the character of the habitat; as in

this instance. - 2. Detail photograph of same nest.

- 3. Another nest, with 4 eggs. Comparison with No. 1 will make it plain that this is

a rather slovenly job.

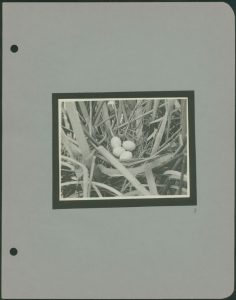

Photographs of nests placed in willow trees. Type II.

- 4. Typical nest, with eggs.

- 5. Typical nest, with eggs.

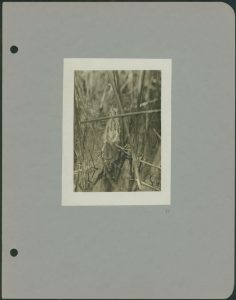

Photograph of a mature least bittern.

- 6. This is the mature bird which I picked up as related in my notes. I placed the

tripod and camera and focused on the reeds; then, holding the bird in my right hand,

I made the exposrue with my left. This is an enlargement from a small portion of the

5×7 plate exposed.

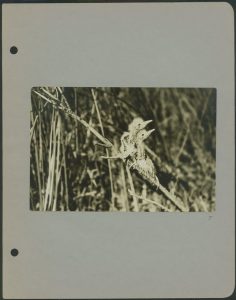

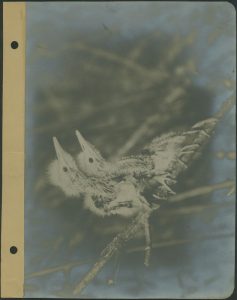

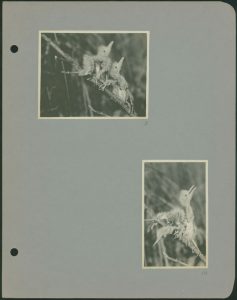

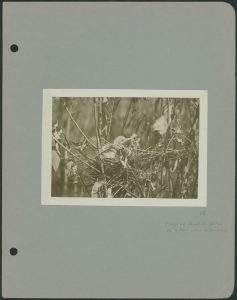

Photograph of the young least bitterns.

- 7. This is the most satisfactory picture which Tros and I got of the two young birds on July 21, 1901. The print is faulty, but I have

no better available; however, I still have the negative. - 8. A too-flat enlargement, from the same negative.

- 9 and 10 record two failures; same pair of birds.

- 11. A young least bittern which I met head on. I was wading in the water to my knees;

moving very slowly I placed my tripod, focused, and made the exposure. I dared not

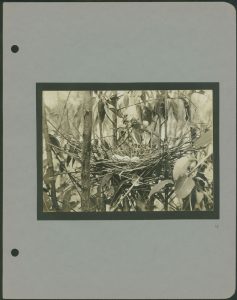

attempt removal of the intervening tule. - 12. Three young least bitterns, in a nest of Type II.

(will be about 25 photos re bittern when assembled)