Great Nebraska

Naturalists and Scientists

Frank H. Shoemaker

Dundy, Hitchcock, Redwillow, Furnas Counties, 1912

cover

1

As a means of getting about indoors, walking is still viewed favorably. But as a means

of covering a number of geographical miles with even a remote idea of getting anywhere

or of deriving pleasure from the process, the ambulatory art is almost forgotten,

and he who fares forth with such a notion is glanced askance by his fellow-men.

The very best way, however, to see and know a region, is to walk through it, as deliberately

as the character of the country traversed and the interest it affords may make desitrable.

It is respectfully urged that he who affects any known method of transportation aside

from his very own two hind feet, misses all but the superficial aspects of the region.

If the journey be by train, the whole visible world resolves itself into two smoky

maelstroms, whirling about the middle distance on either side, and points of interest

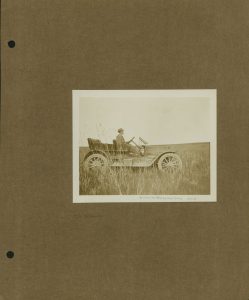

show only for an exasperating second, to disappear forever. If the journey be by automobile

one gets gresh air indeed – – a gale of it; but the transit is rapid (if the Man is

proud of his Car, and he always is), and the field of corn and beans rush by so confusingly

that they “Look like succotash,”during the stray moments when one has no bug in his

eye.If in a moment of insanity a motorcycle be chosen for the trip, it developes that

one’s whole attention is taken by the chugging demon between his knees; he arrives

at his destination, perhaps, but with no clear knowledge as to whether his road has

lead through regions of celestial beauty of sandburs. If a bicycle be considered —

one had better “walk a foot” and use his vision on a broader field than the sordid

ten feet in front of his wheel. Comes now for sentence the obsolescent horse: a good

servant and faithful companion, according to one point of view; according to another,

a creature that cannot adapt himself to circumstances, and an inveterate comsumer

of food and drink, necessitating stoppages at farmes and livery stables and pumps

until he is definitely and mayhap profanely wished at his hoss-telry. And with all

of these unhappy means of transit, one must stick close to rail or road; no rough

country, no tempting creek-banks, no visits to neighboring high points to view the

region in these offensive days of fences; just a melancholy right of way with a pulsing

succession of telegraph poles, or a worn strip of dusty weeds or weedy dust, bound

and bounded by barbed wire.

Take you to your blanket, brother, and learn to love its honest caress o’ nights after

you have legged your leagues and bedded down in the starlight.

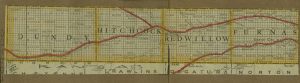

Maps

Maps

2

The soulless corporation positively refused to stop its Denver train at Haigler, the point of my desire. Hence it came to pass that I alighted at Benkelman, at about two o’clock in the afternoon of August 17th. I went into a restautant in

search of information about the region, and the half dozen men who gave me of their

knowledge seemed to have a pretty fair idea of the country. They discouraged my plan

to go northeast of town, as the alleged “canyons” are 12 miles out “and not much

when you git to ’em.” So I inquired about nearer areas of interest, and was told that

I would find, three miles west, a “blow-out” about 40 acres in extent. After my observations

in the great sand area to the northward, where a “blow-out” of two acres is large,

I concluded that this would be worth visiting, and I set out at once.

The most striking difference between this and the other sandhill areas of the state

which I have visited is the continuity here of the vegetation, due to the character

of the soil. In the great sandhill area north, in Cherry County and the tier of smaller counties south of it, the sand is almost pure, and the wind

moves it about so readily that areas fully bound down by vegetation are rare except

in the valleys between the hills. In this Dundee County area the soil is not a pure sand, but in reality a sandy loam, with little tendency

to move under the action of the wind, and as a result the surface is much more

3

closely covered with vegetation. Cultivation here even on the uplands rarely bares

a surface sufficiently sandy to blow appreciably, whereas in the northern area most

breaking of the surface is likely to result in the formation of a “blow-out,” the

sand being so pure and shifting so readily that it will not stay on the job long enough

for crops to get started, though if once established the moisture content is genrally

enough to maintain them through the season after a fashion. In the northern area a

“blow-out” is a deep pit, generally on the northern or western slope of a sandhill,

which the winds “mill” out to a depth of 50 or 60 feet, the diameter being perhaps

100 by 200 feet. And now I was to learn what is called a “blow-out” in this southern

area.

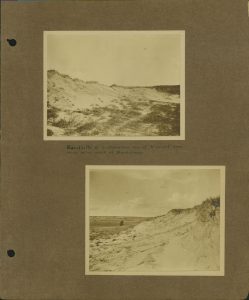

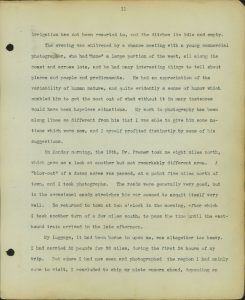

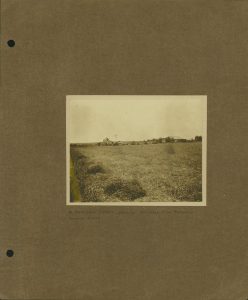

I came upon it from the southern end. It covered perhaps 30 or 40 acres, depressed

from 20 to 40 feet below the general level of the surrounding country. Its general

direction was north and south, it being twice or thrice as long as wide. Its origin

seemed distinctly due to water erosion, with the wind playing a negligible part. A

pond several acres in extent occupied the space near the southern end, and in this

several cottonwood trees, 12 inches or more in diameter, were growing, indicating

that if the pond is present continuously it is doubless generally of much smaller

area; in fact, in southwestern Nebraska this has been the wettest summer in many years.

The surface of the entire depression was generously vegetated, except for a dry creekbed

and lesser drainage areas. At the southeatern end of the

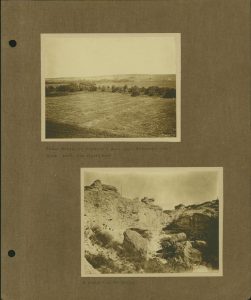

Sandhills at southeastern end of “blowout” and three miles west of Beneklman

3a

3b

3c

3d

4

depression were hills of nearly pure sand, and here the vegetation characteristic

of the sanhil area north was found; “bunch-grass,” yucca, the bush morning-glory,

and species of Psoralea and Euphorbia above the crest, with Redfieldia flexuosa and Phaca longifolia in the active sand. I was interested to note the abscence of Muhlengergia pungens, a grasss which certainly would be present in a smilar area north; I did not find

it anywere in the southern area. Sand lizards, a pugnacious Bembex in numbers, and several specimens of Cicindela formosa-generosa gave to this particular point the faunal aspect of the northern area; but none other

like it was found in this “blow-out,” and in fact few pure sand areas were found in

the portions of Dundy County which I visited. Cicindela cuprascens was common near the water’s edge, and C. punctulata was abundant on a belt lying betwen the moist border of the pond and the sand slopes

above. Several butterflies attracted my attention–Lycaena comyntas, Euptoieta claudia, Nathalis iole, Anosia plexippus, and Aenea andria–the latter being quite numerous, but so wary that I did not take a specimen.

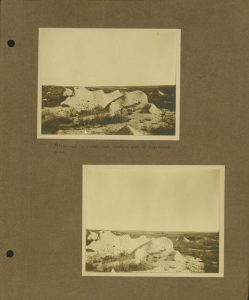

At the northern end of the “blow-out” was visible a confused mass of erosion pillars

and cones–“cores,” they are called locally–and I visited that area. These cones

stand about 20 feet high, and remind one of the band lands formation of Sioux County.

Leaving the “blow-out” after covering it thoroughly, I took to the

5

wagon road leading westward. Patches of alkali-stricken soil appeared here and there,

and I noted one specimen of Cicindela fulgida, true to his habitat. It was now getting dark, and I noted to the southward another

“blow-out,” apparently more extensive and more rugged than the one I had visited.

It was too dark for photography; I had to content myself with a mere sky-line impression.

If the weather had been better I would have camped here, changed my plates, and explored

and photographed the region the next day; but a storm threatened, and the distant

lightning was so continous and brilliant that I could not trust my blanket as a safe

dark-room. So I reluctantly continued my trip.

I stopped at a farmhouse to ease my hunger–one of the most insistent, bothersome,

desirable featurse of these trips afield. It was too late for the evening meal, so

I asked for bread with milk. When I arose refreshed and happy and tried to pay my

bill, the farmer refused payment, and when I persisted he delivered his ultimatum:

“Now look here, stranger, I won’t take your money; so that’s all there is to that. Just you do as much of somebody

else sometime and it’ll all come out even.” A homely and comfortable philosophy which

I encountered more than once in this region.

The road was not good into Parks, but I managed to get over it in the dark and went to the funny little hotel. I was

shown to a room, changed my photographic plates, and descended to view the “squar’

dance”

6

which was in progress; for it was a Saturday Night of Merriment. It was amusing to

see the real pleasure which the dancers were having; it was even amusing to see and

hear the fiddler, who surely will have ultimate pumishment if there be justice in

the universe–though I can not conceive how it may be made adequate. But my amusement

ended here. Hied I to my room after midnight, turned down the top sheet of the bed

* * * * *

I paid my bill at one o’clock, during an interim in the dance, and took to the open–

the glorious, clean open, regardless of whether it would rain or no. The sky was still

overcast, and there was some lightning. It is not easy to find a good sleeping site

in a weedy valley at 1 a.m. And it is not good to get too far away from shelter on

a frowning night. The solution of the problem was found in a prosaic instrument of

commerce known as a cattle chute. It has a gratifying era of desuetude, and I rolled

up in my blanket on this bovine Bridge of Sighs, quite content with the change of

abode, and wondering with some amusement just what the landlord would think when he

viewed the entomological collection which I had left neatly pinned to the table in

my room. I had perhaps fallen short of correct scientific usage by not labeling them;

but almost everyone knows some species on sight.

I got away at daybreak, following the railroad track for a few

7

miles. Crossing the Republican River, I stopped to take a photograph to the north from the bridge, showing some high sandhills

in the distance cut into by the river. My map showed COLFER, in plain, honest print,

as lying a few miles west, and I figured on getting breakfast there. Colfer proved

to be eight feet long, bar-ways, sable on a field argent, supported by pillars gules

dexter and sinister, the whole rampant on a field vert– alfalfa in this instance.

Just a label, without any town to go with it. My trivial mind formulated some absurdity

about the “first Colfer breakfast,” but aside from a passing and lonesome smile at

the conceit I got no comfort out of it. So I visited a farmhouse, where I got a good

breakgast–muskmelons and sass and other frille in addition to the substantials. The

farm was well kept and the people intelligent and courteous. I enjoyed talking over

conditions in the region, and received definite information regarding Trail Canyon, which lies a few miles west. I was told how to cut across to enter its upper reaches

newar the Kansas line, whence I might follow it down to the railroad crossing, and these directions

proved useful.

While on my way across country to the head of the canyon, I found a western meadowlark which was surprisingly tame, and on following it up I discovered that it had been

injured in the breast. It was able to fly short distances and to run freely, and as

it appeared quite normal except on close examination I took a photograph of it as

it ran along the grass ahead of me.

7a

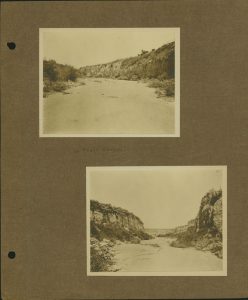

Republican River north from bridge west of …. Sandhills in distance…. feet high.

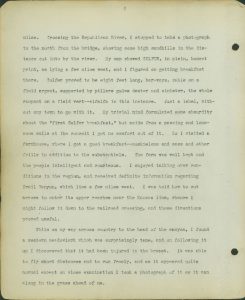

Western Meadowlark

An ant “clearing”

7b

8

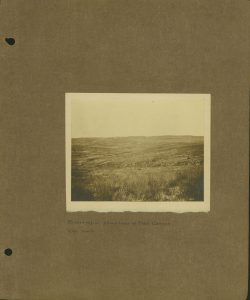

A shiny black grasshopper attracted my attention here. The first one I saw out of

the corner of my eye, and took to be a cricket; but when it got under way it flew

a rod instead of hopping a foot. So I investigated, and collected a number. It proved

to be very common, but I had never before encountered the species.

I also photographed one of the peculiar and clearing common to the plains area. Vegetatin

about the “hill” in the center is entirely absent for a distance of several feet.

Some of these openings are ten feet in diameter; the one photographed was about six

feet.

A photograph was taken of the broken country above the head of the canyon, which gives

a fair idea of the region. The faunal and floral conditions are distinctly of the

plains type. A number of “draws” converge, draining a considerable area into Trail Canyon, which has no running stream, but which is evidently subject to the action of a considerable

flow of water at certain seasons. The characteristic plant of these upper draws–in

their centers, where moisture stays longest–is Euphorbia marginata, the common “snow-on-the-mountains,” and the thousands of these plants with white-margined

leaves were quite attractive.

Trail Canyon, or Corral Canyon, is about four miles long. A dry creekbed of mixed sand and gravel lies between sheer

walls from 20 to 40 feet in height. It is generally not over 60 or 75 feet

9

in width, but in places spreads out to as many yards. There is no rock in its walls

in the lower portion of its extent, but the soil is a consistency which leaves the

walls perpendicular under the erosive influences to which they are subjected. The

accompanying photographs will give a fair idea of the canyon. The Russian thistle

grows everywhere here, in places almost covering the steep walls. During the days

of the “Texas Trail,” when cattle were driven north and south with the seasons, this

natural corral was much used, and its present-day names have come down from that period.

I spent a good deal of time in the canyon, though it was oppressively hot. To lighten

my load, I had eliminated articles which I really needed, notably a canteen and a

poncho. The canteen was missed especially during this portion of the trip; from 8

a.m. to 3 p.m. I had no opportunity to drink, and when I finally emerged from the

canyon I was very thirsty. I went to a farm half a mile distant, where I was given

all the cold water I wanted; and it was a lot. There is an art in drinking water when

one is desperately thirsty. If one dashes into it, buries his nose like a horse, and

drinks like a horse, he is very like a horse, and knows not the joy of dallying with

his thirst. The proper system is to first cool and rinse one’s parched mouth and throat,

to let them know there is something doing at last. Then two or three swallows, not

more; gad, how good it is, and how it permeates! Then a moment of contemplation, gazing

the while

Broken region above (?) head of Trail Canyon View South

9a

“Snow on the Mountain” (Euphorbia maginata)

9b

In Trail Canyon

9c

In Trail Canyon

9d

In Trail Canyon

9e

10

intently into the wealth of the big tin dipper–you miss the essence of the joy if

you don’t look at the water–followed by another pair of swallows. Keep this up for

ten minutes; two blissful gulps of ambrosia to each two minutes. After which, having

trifled sufficiently with your parched system, you will settle down to business and

behave just like the horse; but think how much more pleasure you have had in arriving

at your ultimate satisfaction.

My host was a colored man. He has been in this section of country for over twenty

years, and owns 760 acres. His son owns 240 adjoining, so they have an even thousand

acres between them. His house is small but comfortable, and the living rooms showed

a very fair degree of appreciation of the aesthetics. And he was hospitable indeed;

I did not care to eat, as I had a hot walk ahead, and it annoyed him greatly that

I would not consent to his “firing up” and cooking everything in sight. He named a

number of tempting things, trying to break down my resolve, and incidentally surprising

me at the menu available. I had noticed large baskets of freshly gathered cucumbers

in the kitchen, and finally I compromised by telling him that if he was willing I

would eat some cucumbers. This struck him as the height of the ridiculous, and his

hearty laughter as he made preparations was the only distinctively African thing I

had noted about him, barring his shady complexion. He could not get over the hunor

of my whimsical notion, though his

11

amusement alternated deliciously with periods of depressing solicitude over what those

cucumbers might do to me. But I laughed at his fears and ate my three fine cucumbers,

after which we loafed and visited for an hour, when I arose to take my departure–first,

however, devouring three more cucumers just to show that I was a good fellow. They

were excellent, and if they disagreed with me I humbly beg my pardon, for I was never

conscious of it.

A short distance out of Haigler I was picked up by a Dr. Premer, and hustled over the remaining miles in fine style in his “Reo.” He is a graduate

of the Omaha Medical College, practicing in Haigler, and we had much of interest to discuss. He directed me to a good hotel, and suggested

that if I cared to accompany him he would take me out north in the morning, where

he had calls to make.

I took a walk southward that evening, being rather short of exercise, covering about

six miles in Kansas. Conditions were about the same as those noted about Henkelman; a sandy soil, well covered with vegetation, and few areas inclined to shift. Corn

looks well, promising from 30 to 40 bushels per acre in many fields, the chances being

about equal in fields of early planting badly thinned out by cold wet weather and

cutworms, and replanted fields rapidly maturing but in danger of destruction if heavy

frosts come early. There has been so much moisture in the Republican Valley this season that

12

irrigation has not been resorted to, and the ditches lie idle and empty.

The evening was enliveded by a chance meeting with a young commercial photographer,

who had “done” a large portion of the west, all along the coast and across lots, and

he had many interesting things to tell about places and people and predicaments. He

had an appreciation of the variability of human nature, and quite evidently a sense

of humor which enabled him to get the most out of what without it in many instances

would have been hopeless situations. My work in photography has been along lines so

different from his that I was able to give him some notions which were new, and I

myself profited distinctly by some of his suggestions.

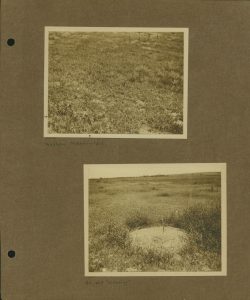

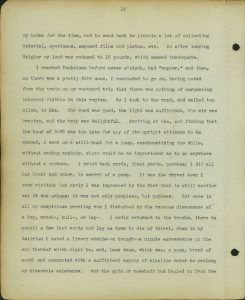

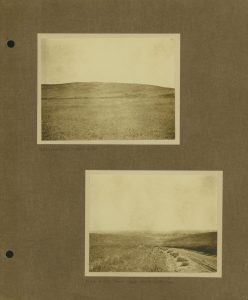

On Monday morning, the 19th, Dr. Premer took me eight miles north, which gave me a look at another but not remarkably different

area. A “blow-out” of a dozen acres was passed, at a point five miles north of town,

and I took photographs. The roads were generally very good, but in the occasional

sandy stretches his car seemed to acquit itself very well. We returned to town at

ten o’clock in the morning, after which I took another turn of a few miles south,

to pass the time until the east bound train arrived in the late afternoon.

My luggage, it had been borne in upon me, was altogether too heavy. I had carried

32 pounds for 36 miles, during the first 24 hours of my trip. But since I had now

seen and photographed the region I had mainly come to visit, I concluded to ship my

plate camera ahead, depending on

13

my kodak (sic) for the time, and to send back to Lincoln a lot of collecting material,

specimens, exposed films and plates, etc. So after leaving Haigler my load was reduced to 15 pounds, which seemed inadequate.

I reached Benkelman before seven o’clock, had “supper,” and then, as there was a pretty fair moon, I

concluded to go on, having noted from the train on my westward trip that there was

nothing of surpassing interest visible in this region. So I took to the road, and

walked ten miles, to Max. The road was good, the light was sufficient, the air was bracing, and the trip was

delightful. Arriving at Max, and finding that the hour of 9:30 was too late for any of its upright citizens to

be abroad, I went on a still-hunt for a pump, anathematizing the while, without naming

anybody, whoso would be so improvident as to go anywhere without a canteen. I tried

back yards, front yards, porches; I did all but break and enter, in search of a pump.

It was the dryest town I ever visited; but early I was impressed by the fact that

in still another way it was unique; it was not only pumpless, but pupless. Not once

in all my suspicious prowling was I disturbed by the raucous dissonance of a dog,

watch-, bull-, or lap-. I sadly returned to the tracks, there to pencil a few last

words and lay me down to die of thirst, when in my delirium I noted a livery stable–a

trough–a minute excrescence on the end there of which might be, and laus deus, which

was, a pump, broad of mouth and connected with a sufficient supply of alkaline water

to prolong my miserable existence. And the gods or somebody had hauled in from the

“Blowout” five miles north of Hangler (?)

13a

Dr. (?)

13b

Dr. (?)

13c

14

fields a load of fresh alfalfa hay, and left it by the stable! I took off my shoes

and leggins, unfurled my blanket, got into my mosquito hood, snuggled down in the

fragrant softness of the hay with a loving last look at Lyra and some other overhead

friends, and lost track of things. A wandering nag ate part of my bed during the night,

but I managed to keep most of it.

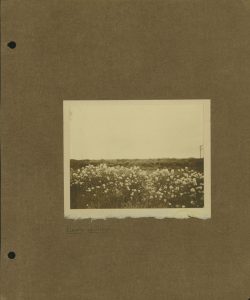

At 5:30 I started east, after another alkaline draught, and walked ten miles to Stratton. The country was become depressingly agricultural; corn and alfalfa everywhere, and

nothing to interest me. I had hoped for a wilder region, with things to investigate

and photograph; and here was the country-side disfigured with crops, ruining the scenery

and leaving me morose and dangerous. Here and there, however, there was a stretch

of hopeful uselessness–areas give over to Russian thistle and Cleome, the latter growing abundantly along the roadside. It is a handsome flower, and I

photographed in the early morning light a characteristic section of the miles-long

patches. One often gets much better perspective and very much superior tones by attending

to his photography when the sun is not shining; this subject would look like wall-paper

if attempted at noon.

I reached Stratton shortly ahead of a storm which has closed in rapidly from the southwest. The rain

started at nine o’clock and lasted until nearly noon–a steady rain which ruined the

roads and my disposition, for I had hope to reach McCook, 42 miles, before night. But the region

15

did not promise much of interest, so I loafed around town until a freight train came

along in the afternoon, when I rode to McCook. This is, I believe, the first ride I have had in a caboose within a dozen years,

and I rather enjoyed the experience. It was entertaining to look out through the stingy

port-holes, and to wonder just what curse holds cabooses beyond the reach of evolutionary

processes which get in their work on everything else. I very much doubt if one nail

or plank of variation from the original perfect caboose has occurred in all these

decades. But the caboose was made glorious by the presence of a returned Ulysses;

one who had parted with his holdings hearabouts these three years agone and wandered

into the remote northwest to till its soil, and was now returned with tidings. Truly

the long-bow is a wondrous weapon when its clothyard shafts are drawn to the head

by a master-bowyer: and here was one indeed. The particular region of which he spoke

I know sufficiently to appreciate most of the points where it was evident that “the

narrow partition between his memory and his imagination had broken down,” and I had

really a most pleasant ride, listening to this Marco Polo. His auditors were two neighbors

of former days, and he was trying to sell them some lands out yonder because he had

too much. The price had descended from $50 to $15 before they passed out of my life

at McCook. All of this information came perforce, since the trio had the farmer’s habit of

yelling instead of talking, and every word carried triumphantly over the creaks and

groans of the red caboose.

15a

Dr. (?)

15a

16

At McCook I went to a hotel, and spent the evening variously–a hot and several cold baths,

a little writing, some reading of magazines. In the morning I tried to find my friend

Prof. Pool, of the botany department at the university, whom I knew to be at large in this region;

but it appeared that he would not reach town until the 9 o’clock train arrived that

night. I took a long walk, and returning in the afternoon had two hours with Senator Cordeal, who is a painstaking student of the early history of the state, and who had much

of interest to tell me about the regions I had visted–thrilling tales of Indian battles,

the massacre of surveying parties, and attacks on wagon trains. He has in mind an

attempt to identify Fremont’s route through this region, and suggested the possibility

of our taking the trip together next season.

At nine o’clock I went to the depot to meet Pool. He and his wife alighted in due course, and I applied for the job of carrying his

suitcase, for a consideration, but as luck would have it, he recognized me, and I

had to carry it along for nothing. So I went “home” with him, and after a visit I

turned in, a tent pitched in the yard proving to be a lot more fun than any hotel

I wot of–even a good one. I stated the probability of my decamping before they were

up in the morning, and was immediately voted down and placed under heavy bonds to

appear at breakfast.

We had a pleasant chat in the morning, and afer a breakfast which I like to remember

I struck out southward, at 9 o’clock. My destinat-

17

tion now was Cedar Bluffs, Kansas, about 19 miles south and slightly east. I was leaving the valley of the Republican

to enter that of the Beaver. These valleys are separated by a high ridge, and I took

two or three photographs before reaching the summit. One of these shows a ruined soddy,

with the high weeds growing about; another shows “cat-stairs”–loess slips–on a distant

hillside; and another a view from the heights back towards McCook. I did not follow the direct road, but put in several extra miles going east and

west, collecting specimens and amusing myself. It is part of the fun not to be in

a hurry, and to arrive only when and not until you get there–wherever that is.

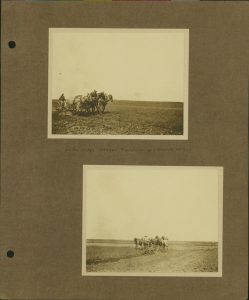

Near the crest of the ridge, where the hypothetical drop wavers as between the Republican

and the Beaver, I came across a farmer preparing to hitch five horses to a plow. I

got to thinking what if I had to do it myself and nothing to eat until I did it; and

the thought was so disturbing that I concluded to learn. So I dropped everything and

looked on. The farmer was a jolly big young fellow, tanned like a Turk, and quite

inclined to sociability; so I hung around and watched. While he was assorting his

beasts and giving them places and hades, he found time to take a lively interest in

my affairs; want to know where from, where to, why, and how; and I told him fully.

He had tagged me as a professional walker, and supposed I was

“Blowout” five miles north of Hangler?????

17a

17b

17c

18

doing it on a wager, only I was too white; had I been sick, or just inside? I could

not resist it: I told him “Inside, sick; sick inside” –just for the beautiful sound

of it; and when he roared his appreciation I admitted that it was an untruth; that

I had been inside, but not sick. He was still rankling over the affront given him

by a “professional” during a previous seasons; upon being offered a ride to town the

man had declined, stating that he was in a hurry. — I believe I could anchor five

horses to a plow, but I never expect to.

Over the ridge, with the beforementioned hypothetical drop seeping merrily toward

the Beaver, I photographed a farm, to show the penchant of the agriculturalist to

drain his barnyard through his dooryard. What’s the use of picking an easy one like

“the way of a serpent upon a rock” when a hard nut like this is hanging from the shagbark

bough? If you want entertainment, just take to noticing farm layouts, and see how

often this happens. And notice how many farmhouses are entirely unscreened; and how

few farmers know what “ventilation” means; and observe the chumminess of the hogs

and chickens with the back (or front) door; and contemplate the milk-cans unwashed

and with the lids off, and the garbage scattered about the dooryard or standing in

buckets or boxes. If farmhouse were huddled together as town and city houses are,

with the utter disregard or ignorance of sanitation which is almost invariable, there

would not be

19

a farmer extent in a few weeks, which would be annoying.

I went to a farmhouse for a drink, and as the place looked reasonably clean I asked

if I could get something to eat. Little Brother went in to inquire, and came back

to say naively that Sister said that Father was away, and that she was afraid I couldn’t.

So I tried another farm a mile farther along. Baching; had two spuds cooked but ate

’em himself; nothin’ goin’ forward in a food way until dark. He was mowing Bouteloua oligostachya, which he informed me was buffalo grass. Being hungry and a little peevish about

the spuds, I let him go hang with his mildewed botany. Taking up two notches in my

belt, I went to another farm–two miles–and walked up to the door. A bewhiskered

farmer was tilted back in a chair against the wall. A boy of 14 was tilted back in

another chair against another wall. A girl of 17 was tilted back in another chair

against nothin’. I asked if I could get something to eat. The farmer said naught,

but looked quizzically at the girl, who also said naught. After contemplating the

girl for about a minute, the farmer turned his head languidly in my direction and

said, “It was only yesterday two fellers come through here and wanted something to eat.” “Well,” I remarked, as I

took up my luggage, “it seems to me they showed darned poor judgement.” And I trudged

sternly out of the yard. For about a minute I was mad, plenty, for I was hungry; but

after the scant sixty seconds had

A Nebraska farm showing …..

19a

20

elapsed I got my bearings and saw only the ludicrous aspect of my hard luck. But three

efforts were enough; the whole ridge was evidently proof against invasion, and remembering

that two fellers had ravened through the region only a short twenty-four hours previous, I

decided not to trifle with the overwrought natives. On the strength of two more notches,

I got across the inhospitable Red Willow county line, and in free Kansas, at Cedar Bluffs, made bold to purchase food at an inn.

I then proceeded to visit the rocky outcroppings on the south side of the Beaver from

which the town takes its name. I took a number of photographs of Cedar Bluff (see foot-note, and pray for me.) I show herewith my one extant photograph of Cedar Bluff–also a distant view with I took from near the Nebraska line.

Some of the cedars among the rocks are of considerable age, though most of the trees

are young. I was interested to note the Mexican falcon, the rock wren, and the turkey

vulture. I collected a specimen of the large moth Erebus odora, which works up sparingly

Upon my return to Lincoln I developed five rolls of film one morning. Everything was lovely. Returning in the

afternoon I developed the remaining two rolls (18 films). They were ruined. Investigation

disclosed the entertaining fact that between 12 noon and 2 p.m. the plumbers had put

in some pipe on the floor below the laboratory in which I was at work, and had got

enough acid or profanity or something into the water to bring about the result described.

21

from the deserts of the southwest into our sandhills each summer. The region looked

very snaky and inviting, but I did not succeed in finding a rattlesnake.

I have read that in England the penalty for walking on a railroad track is arrest,

while in American it is death. In spite of this, I took to the rail for a time after

leaving Cedar Bluff, for it is the most direct route and the track is “mud-ballasted” and consequently

upholstered with a fine crop of grass. The path in the middle afforded fine walking,

and aside from a turn of a few miles north to view the country, I stayed by the track

through Marion and Danbury.

At the latter place , in the absence of anything to eat, I bought some cookies, and

in the absence of any civilized drink, a bottle of pop; for I had had enough of going

to sleep without a drink. Laden with this cargo, I lay my course due eastward until

two bells of the first night watch (9 p.m.; landlubbers please note), when I spoke

a square-rigged alfalfa stack anchored two cable lengths to larboard, and hove to

under its bows in about two fathoms of dew, having run my 36 knots( 42 jog-graphic

miles). I wound my watch, but didn’t set any, and this came near being my undoing.

I had impartially divided my cookies as between “supper” and breakfast. Having eat

my supper cookies and my grop, I turned in, becoming aware after an interval that

I was being boarded by a pirate, and to make it more confusing, that he expected me

to board him. A mouse had got into the hold and

Cedar Bluffs in distance…..

A…..

21a

22

22

was making away with my breakfast. I repelled the boarder; then I got out a cookie,

broke off a piece, and put it down in the moonlight where I could watch it. Presently

the marauder came hitching along, and carried it away. So I gave him another piece,

and he carried it away; and so on until I finally went to sleep— —if I remember rightly,

with about half of the cookie in my fingers, in which event he must have taken liberties

with me, for it was not there in the morning.

That was a fine night, there on the south side of the stack. I had pulled down enough

alfafa to make a soft bed, and rolled up in my blanket on this. The night was perfect;

the moon almost full and very brilliant; the constellations Scorpio and Sagittarius,

which I like more than all the rest, showed clearly in spite of the bright moon. It

was great; the beautiful night, the comfortable bed, the wholesome fatigue, the profound

sense of physical well-being, the companionable mousie, all.

I have previously mentioned my mosquito hood, but only incidentally, and it certainly

deserves a few words, since it is indispensable to one’s comfort on a trip of this

character. It is a contrivance of three flexible steel hoops, sewed parallel to each

other four inches apart, on the inside of a cylindrical bobbinet hood with a closed

top, sixteen inches in diameter and two feet “high.” The steel is so flexible that

the whole may be folded in small compass and put in a pocket. Getting into this affair

and tucking the skirts into the top

Beaver Creek (?) — near Beaver City

22a

23

23

of one’s blanket, the wires hold the bobbinet several inches from one’s face and ears,

and forthwith the murderous soprano of my lady Anopheles becomes sweet music. Every night I spent out the mosquitoes were abundant and bloodthirsty,

and without the hood my rest would have been badly broken. And it keeps off larger

prowlers also, when I awakened in the morning there were generally a number of grasshoppers

walking around on it, looming large against the sky.

I awakened entirely refreshed at 6 o’clock, and after partaking of my jealously protected

breakfast I started anew down the upholstered track. The disgustingly fertile condition

of the country continued, and increased, and I found little to interest me; for I

can find nearer home all the cornfields I need. I followed the track most of the day,

making a detour of a few miles north of Wilsonville, but finding nothing to pary for the extra miles. I took several photographs showing

agricultural and other conditions, but these do not appear, for reasons touched upon

in carefully guarded language on page 19.

At 4:30 I reached Beaver City, to which point I had shipped my camera and some clothing a trifle more conventional

that that I was wearing; for I had anticipated that the interest of the walking tour

would pale at about this point. The 78 miles I had walked in the past two days had

not exhausted me physically, but the cornfields had, and I was ready to quit walking.

24

I had not anticipated spending more than a few hours in Beaver City, but I found four reasons

why I should stay longer; and it took me three days to find the depot. My visit there

was filled to the limit — —long drives and walks, a party, a picnic; one of the most

enjoyable “times” I ever had. But this narrative has to do with my walking tour, and

since that ended with the 170 miles covered afoot west of Beaver City, I shall not fill that additional pages which suggest themselves almost ready writ.

I had another pleasant visit at Superior, an account of which is omitted for the same reason, and reached Lincoln after an absense of twelve days, beautifully tanned and freckled, and taking deep

breaths after a manner I had almost forgotten.