Great Nebraska

Naturalists and Scientists

Frank H. Shoemaker

Sidney, Banner County, Scotts Bluff, July 30-Aug. 9, 1911

cover

cover

Iv. – Sidney, Banner County, Scotts Bluff

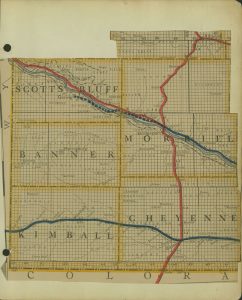

map

map

Near….

1

Our party of four left Thomas County on the evening of July 30th for a short visit to Banner County. The best we could

do in planning our trip west from Halsey was to leave there in the evening, spend

the night at Seneca, and take a morning train to Sidney.

The western boundary of the sandhills is sharply marked in the region traversed by

the railroad. About three miles east of Alliance the sandhills end abruptly, and the

transition to clearly defined plains conditions is immediate, this definition being

visible from the car windows for several miles north and south. To the southward,

however, the line of sandhills swerves sharply to the westward, roughly paralleling

the valley of the North Platte River, so that the true sandhill area is again entered

about five miles south of Alliance. New flowers appeared in numbers, notably Mentzelia,

prickly poppy, and mallows.

Crossing the North Platte River at Bridgeport, the sandhill area is soon passed and plains conditions again prevail. I tried a

photograph from the moving train near Vance, with fair success, the object being to show the character of the strata on high

points in the region.

2

Arriving at Sidney in the early afternoon, and having the time at our disposal until midnight, we undertook

short trips into the neighboring county. The botanists went northwest, while Dr. Wolcott and I went northeast and devoted our attention to insect collecting. Several species

of Eleodes were found, and the first Solpugids of the trip. These anomalous creatures were very interesting to me, as I had never

before seen them, and the Doctor’s advice not to pick them up with my fingers was

entirely unneccessary; their plainly visible jaws and their pugnacious attitude when

disturbed were sufficient deterrents in themselves, and my captures were made with

circumspection and tweezers. The bite of these animals is said to be extremely irritating,

and is doubtless worse than that of any spider found in Nebraska, though probably

not in any sense dangerous.

From the region north of Sidney we cut across town to the region south, where Lodge Pole Creek was visible, and this we followed for a mile or two.

Birds observed at Sidney

- Dove

- Western nighthawk

- Desert horned lark

- Kingbird

- Arkansas flycatcher

- Western meadowlark

- Brewer blackbird

- Western chipping sparrow

- Western lark sparrow

- Western goldfinch

- Lark bunting

- Cliff swallow

- Yellow warbler

- Brown thrasher

Butterflies

- Danias archippus

- Colias philodice

- Lycaena melissa

Aside from these notes, there is little to record for Sidney, but the short trips we made there furnished an interesting check on other collecting

in the plains region. The similarity of its forms wherever we studied conditions was

most striking.

3

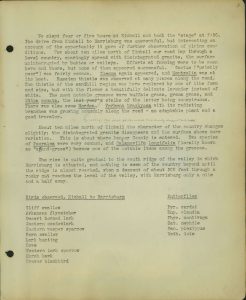

We slept four or five hours at Kimball and took the “stage” at 7:30. The drive from Kimball to Harrisburg was uneventful, but interesting on account of the opportunity it gave of further

observation of plains conditions. For about ten miles north of Kimball our road lay through a level county, sparingly spread with disintegrated granite,

the surface uninterrupted by buttes or valleys. Efforts at farming were to be seen

here and there, but none of them appeared successful. Cactus (“prickly pear”) was

fairly common. Cleome again appeared, and Mentzelia was at its best. Russian thistle

was observed at many places along the road. The thistle of the sandhill region was

here replaced by one of like form and size, but with the flower a beautifully delicate

lavender instead of white. The most notable grasses were buffalo grass, grama grass,

and Stipa comata, the last year’s stalks of the latter being conspicuous. There was also some Horden.

Verbena brachyosa with its radiating branches was growing commonly along the road – an adaptable plant

and a good traveler.

About ten miles north of Kimball the character of the country changes slightly; the disintegrated granite disappears

and the surface shows more variation. This is about where Banner County is entered. Two species of Psoralea were very common, and Calamovilfa longifolia (locally known as “stand-grass”) became one of the notable items among the grasses.

The rise is quite gradual to the south ridge of the valley in which Harrisburg is situated, and nothing is seen of the country beyond until the ridge is almost

reached, when a descent of about 300 feet through a rocky cut reaches the level of

the valley, with Harrisburg only a mile and a half away.

| Birds observed, Harrisburg to | Butterflies |

| Cliff swallow | Pyr. Cardui |

| Arkansas flycatcher | Eup. Claudia |

| Desert horned lark | Phyc. Montivaga |

| Western meadowlark | Sat. nephile |

| Western vesper sparrow | Dan. Plexippus |

| Barn swallow | Nath. Iole |

| Lark bunting | |

| Dove | |

| Western lark sparrow | |

| Marsh hawk | |

| Brewer blackbird |

Butterflies

- Pyr. cardui

- Eup. claudia

- Phyc. montivaga

- Cat. nephile

- Dan. pleippus

- Nath. iole

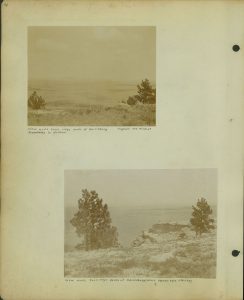

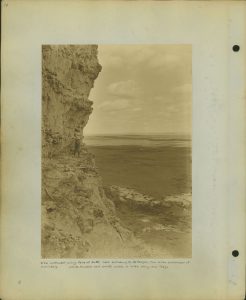

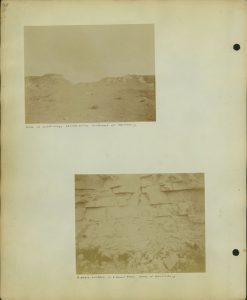

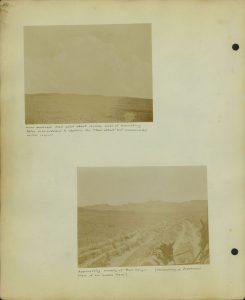

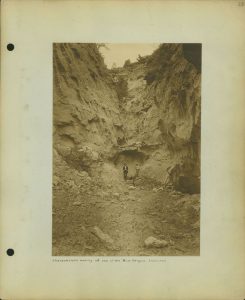

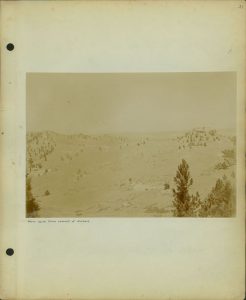

View north from ridge…….

View north from…..

4

View north from ridge southeast of Harrisburg

5

View eastward along faceof ridge south of Harrisburg

6

7

Harrisburg is situated in a valley which runs east and west, and which averages about ten miles

in width. The southern side of the valley is marked by bluffs from 100 to 300 feet

high, with rocky buttes standing out sharply and separating the draws which lead up

into the bluffs, and which in the language of western Nebraska are called “canyons” – a much abused word, signifying anything from a bare fifty-foot

gully to an entire valley and its numerous branches. The ridge to the north of the

valley is higher and less broken, and the prominent points are called the Hogback Mountains and Wildcat Mountains, each consisting of one peak, so the plural form of the names is honorary. Their

altitude is about 5300 feet, perhaps 500 feet above the low points of the valley.

The town of Harrisburg consists of half a dozen stores, a courthouse, a hotel, and a few accidental houses.

It looks very lonely from the heights. We entered it with fear and trembling, for

it was beyond reason to expect proper accommodations in the little one-story hotel;

but a gratifying surprise awaited us, for the place was well kept, the food was good,

and the people were very accommodating.

The collecting in the valley was strictly of plains forms, to a great extent identical

with those found at Sidney and in similar localities in Sioux County. The most striking thing was the abundance and variety of Eleodes; we found nine species during our stay there and several closely allied forms. It

is doubtful whether there is another locality in the country which would yield as

many. The numbers ranged from hundreds or thousands of the common species to two individuals

of the biggest, rarest one – not before taken in Nebraska. As the valley proper is entirely destitute of wood, and without the yucca plants

common throughout most of the region, the only shelter for these insects was found

in burrows or under dry cow-dung; upon kicking over one of these insects, sometimes

three or four species together. Toward evening and on cloudy days they moved about

freely, and these occasions furnished our best collecting. The first examples found

of any species were cherished as great discoveries, when perhaps within twenty-four

hours we would encounter a “run” of the kind and they would soon be classed as too

common for further collecting. I was the fortunate finder of the first “big fellow,”

which is about the size, shape, and color of the south half of a five-cent cigar.

For three days thereafter the Doctor stalked about green-eyed and morose until he

found one, and then the atmosphere cleared. He squared matters by finding the only

Solpugid found in Banner County.

In the canyons the collecting was more varied, but extremely limited none the less,

on account of the very dry season. Most of these are

Nest of

8

9

“dry canyons,” and the fauna is correspondingly limited; but in the vincinity of Gabe Spring and Long Spring we found a few species of Bembidium and other beetles. We collected three centipedes under rocks and logs in the canyons,

the largest being about five inches long and of uncanny mien, though probably not

large enough to be dangerously or even troublesomely poisonous. The only tiger beetles

seen in Banner County were Cicindela punctulata, which was abundant, and one example of the variety micans, the blue form. Of this

latter, however, the botanists reported having seen numbers near Wildcat Mountains on one of their trips.

Among the birds we found several things to interest us. The full list of species observed

will be given later.

Naturally, raptorial birds abound in this country of buttes and cliffs. We found several

old nests of the ferruginous rough-legs nest on the summit of a butte by preference,

generally in a commanding position with an outlook in all directions. The nest photographed

(page 8), evidently used the preceding spring, shows a typical site. The Krider Hawk, on the other hand, nests on a ledge against a wall, and the birds show remarkable

ability in selecting places which are inaccessible to mere human beings. Frequently

the nesting site is used for many years, and the result in some instances is an accumlation

of surprising dimensions – one such nest found on the ridge south of Harrisburg being fully eight feet in length, though limited in the other dimension by the narrow

ledge on which it was placed. The western horned owl, nesting very early in the year, often uses the Krider premises before the hawks get ready. One such partnershup affiar was found on one

of the buttes south of the valley; we could not reach the nest, but the evidence at

the base of the cliff was sufficient, for there were great numbers of the regurgitated

pellets which signified the presence of the owls, and there were also remains of animals

which would not be found during the time the owls were nesting – notably the skeleton

of a fine large rattlesnake.

The big butte near the mouth of what we have termed in our notes 3d Canyon, in the

absence of a name, was the favorite haunt of the white-throated rock swift, which I had seen at a distance in Sioux County, but with which I really became first acquainted here. The flight of these birds

is wonderful; apparently they fly for the love of it, describing great circles out

over the valley and returning to the bluff with a whiz of wings which may be plainly

heard for a distance of several rods – though any such long-distance listening is

needless, for they delight in dashing by within a yard of one’s head. On the occasion

of our first climb up this butte we saw the birds entering a hole near the top, at

a point which

Nest of

10

11

we could not reach; but as we were descending I chanced to see one of the birds entering

a hole on the ledge where we had been standing a moment before, and we went back to

investigate. We had examined the holes along this ledge, and far back in this same

hole had seen what we supposed to be some small mammal, too far in to reach. More

careful observation now showed it to be a swift, and we undertook to get it out, using

sticks which had been generously shed by a Krider’s nest above. A little careful poking started something, and before we realized it

a swift had shot by like a streak of light., There was another inside, however, and

this we managed to reach and get in our hands, where it was many, many removes from

the handsome creature it is on the wing; the white parts of the body were dingy and

soiled, and the creature was alive with “vermin.” So after a casual examination, and

after borrowing a few samples of its lice, the bird was released, taking with it the

wraith of another illusion. We then examined the nesting cavity, which had evidently

been used this season; some of the birds flying about appeared to be of this year’s

brood. We found pseudoscorpions, mites, mallophagids; and best of all, Dr. Wolcott found a minute, wingless beetle. When this was noted we set about a careful examination,

and on this and a succeeding visit secured 22 specimens. It is a tiny, brown, degenerated,

parasitic thing, about one-twentieth of an inch long, and it took us over three hours

to collect them – three hours of unpleasant work, for we had to reach in with our

bare arms to get the refuse material about the nesting cavity, and the while mass

was full of minute dry spines from the prickly pear, which we remembered frequently

for many days. How did they get there? Carried by bird or mammal, and why? The wind

was blowing sharply, and down on our knees on the narrow and delightful time of it

going over this stuff, which was as dry as powder and as corrupt as time could make

it, and which the frisky breeze tossed into our faces a hodful at a time. But it is

almost certainly an undescribed species, and we were anxious to collect as large a

series as possible.

In addition to the insects taken in the nest, there were numerous slate-colored ticks,

some of them as much as one-eight of an inch in length, crawling about the surface

of the rocks, and of these we collected a number. They probably infest some of the

inhabitants of the cliffs, as they were found also in the masses of guano with which

many of the holes were filled.

White-throated rock swifts were noted also later in Bull Canyon, 14 miles west, and about buttes below the Hogback Mountains, 8 miles north of Harrisburg.

In 3d Canyon we found a nest of the rock wren with young birds. The nesting site was

a hole in a pile of rocks, only a few feet above the bottom

Cavity occupied by …. swifts

12

… Harrisburg

13

Bluff…

14

Another view…

Western…

15

Nesting….

16

Another view…

Western…

17

Another view…

Western…

18

19

of the ravine, and the young were easily reaches. There was a recess in the back of

the cavity, however, and I could see two of the little fellows crowded into this;

probably there were others. I managed to get two of them out and coaxed them to “sit,”

though they were most unwilling subjects, and the resulting photographs do neither

them nor myself credit. The parent birds were busy feeding young in the neighboring

trees, and on investigation we found that a well-grown young cowbird was the subject of their solicitude. This rather surprised us, for it would not seem

possible for a cowbird to enter the nesting cavity; but the evidence points the other

way.

Numerous old nests of the desert horned lark were discovered about the valley; we ran across probably as many as fifteen or twenty

of these.

Dr. Wolcott found a nest of the mourning dove on the side of a steep slope on the ground among

the vegetation, and I obtained a photograph — one young bird, and an egg which was

probably infertile.

Cedars are the prevailing conifers on these buttes and ridges, which is in rather

interesting contrast to Sioux County, where the cedars are not common. Bull pines are present here also. Aside from the

larger size of the Sioux County ridges and canyons, and the presence of streams in most of the canyons, the general

appearance of these regions here is much as it is there.

We met a Dr. Page in Harrisburg, a Yale graduate who practiced medicine among the Sioux Indians for some years and

then in the absence of anything worse to do drifted into this country. He is now county

clerk, and showed us in his office maps indicating Bull Canyon, situated in the western part of the county and very near the Wyoming line. It is in this region that the highest altitude in Nebraska is recorded – 5360 feet – not on a peak, but on a rolling plateau above the canyon.

He pointed out this region as a desirable place to visit this interesting region,

of which we first learned after their departure. It was impossible to get a livery

rig, and the account of how we got our team would be quite a story in itself – and

a photograph of the team would bear out the story. We finally got the component parts

together – one horse about 17 hands high and the other apparently about 7, and with

no more ambition than a peddler. We did not get started until noon, and then bade

fair to ride into a heavy storm, which, however, passed along the north side of the

valley, Hogback and Wildcat

Another view…

Western…

20

21

being veiled in rain for some time. A peculiar feature of the storm was the presence

of a strong wind from the northwest in its wake, while the storm itself moved northeast.

This wind was remarkably cold, from which we inferred that it had been accompanied

by hail, though it had the appearance of a rain-storm. We passed Gabe Rock, a massive detached butte set out from the south ridge, and followed the valley westward,

past Long Canyon, which looked rather uninteresting, and at about two o’clock reached the entrance

to Bull Canyon. The entrance was quite commonplace, and gave no indication of the things beyond

– which suggests the possibility that I may have misjudged the quality of Long Canyon as well.

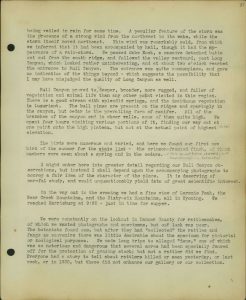

Bull Canyon proved to be deeper, broader, more rugged, and fuller of vegetation and animal life

than any other point visited in this region. There is a good stream with splendid

springs, and the deciduous vegetation is luxuriant. The bull pines are present on

the ridges and sparingly in the canyon, but cedar is the prevailing form of conifer.

All of the branches of the canyon end in sheer walls, some of them quite high. We

spent four hours visiting various portions of it, finding our way out at one point

onto the high plateau, but not at the actual point of highest elevation.

The birds were numerous and varied, and here we found our first new bird of the summer

for the state list – the crimson- fronted finch, of which numbers were seen about a spring and in the cedars.

I might enter here into grater detail regarding our Bull Canyon observations, but instead I shall depend upon the accompanying photographs to convey

a fair idea of the character of the place. It is deserving of careful study, and would

unquestionably yield data of great scientific interest.

On the way out in the evening we had a fine view of Laramie Peak, the Bear Creek Mountains, and the Sixty- six Mountains, all in Wyoming. We reached Harrisburg at 9:30 – just in time for supper.

We were constantly on the lookout in Banner County for rattlesnakes, of which we wanted photographs and specimens, but out luck was

poor. The botanists found one, but after they had “collected” the rattles and fangs

as souvenirs there was little desirable about the specimen for pictorial or zoological

purposes. We made long trips to alleged “dens,” one of which was so notorious and

dangerous that several acres had been specially fenced off for the protection of grazing

stock; but not a rattler did we find. Everyone had a story to tell about rattlers

killed or seen yesterday, or last week, or in 1880, but these did not enhance our

gallery or our collection.

In…. canyon

22

Characteristic ending of one of the …. Canyon….

23

View…..

24

In…. canyon

25

View…..

26

27

View…..

28

Nest of….

28

29

On August 7th we started at 8 o’clock in the morning for Hogback and Wildcat Mountains, having arranged to meet the stage with our baggage at a ranch near the north ridge,

four miles east of Wildcat.

We stopped at a ranch two miles south of Hogback, and found it the best kept place we had seen, with carefully irrigated garden and

better – looking crops than usual in this region. The lady of the house was alone,

and she laughingly admitted while she geared up the windmill to give us a drink that

when she had seen us coming she had locked the door, but that a nearer view had convinced

her that we must be the “unversity people” of whom she had read in the paper. All

summer long we were well advertised wherever we went, but the news always came to

us second-hand; I do not think a member of the party saw a line of print about our

crowd. Doubtless this was a distinct loss to us, for the country write-ups of such

freaks very likely would be good reading. And in this connection, for want of a better

place, I shall mention the fact that throughout our travels it was gratifying to note

the spirit of friendliness which prevails toward the university. The people of the

state evidently believe in it and are proud of it, and the courtesy and good will

which we met everywhere on account of our connection with the institution are a matter

of pleasant memory. – Our kind lady proved to be a sister- in- law of Prof. Seth Meek, the noted ichthyologist, whom Dr. Wolcott and I both know. Also she took us into the springhouse for a drink of cold milk,

and brought us each a big piece of angel-food! Although I think there was little about

our appearance to suggest either as entirely appropriate, we accepted both without

argument.

It was necessary to carry my large camera on this trip, to get some pictures in the

“mountains,” also my tripod, also a number of alcoholic specimens which could not

be trusted without a guardian on the stage, also a canteen and my small camera, my

spider- collecting case, and my creel with various implements and instruments and

boxes and bottles. The outfit weighed about twenty-five pounds on starting, and the

weight increased in geometrical ratio all day. By the time we reached the summit of

Hogback I was about as nearly “all in” as on any occasion of conveniently recent memory,

and the hot water from my canteen was as sweet as nectar. It is surprising how good

any kind of water is when one is really thirsty; in our various trips in bad lands

and sandhills and among parboiled buttes this summer I found opportunity to prove

this. Dr. Wolcott offered time and again to hlpy me out with my load, as he was traveling light; but

it is one of my fool theories that if a fellow can not carry his own stuff he ought

to stay at home, or hire a dray, and I tried all summer to live up to this idea.

Near Hogback, in the valley, we found a sand dune three or four acres in extent and about 30 feet

high. To the west appeared a depression from which

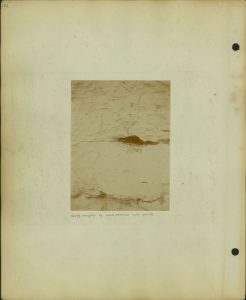

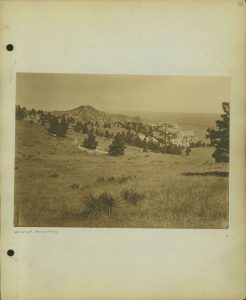

Hogback Mountains….

30

View north from….

31

View from….

32

View north from….

33

Nesting site…

34

35

the sand had come – a most interesting example of the formation of a blow-out, and

much more striking on account of being isolated. I took a photograph of this sand-dune

and the depression from a point half way up Hogback. Other blow-outs were visible to the west.

Climbing up the west side of Hogback, we found rock swifts in possession of favorable buttes, turkey vultures circling about the summit, and old nests of Krider hawk in characteristic places. Our only zoological “take” was a battered specimen of Papilio zolicaon.

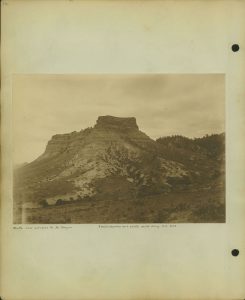

The Wildcat Mountains were near by, but Hogback is higher, we had obtained the photographs we desired, and we concluded not to visit

that point; but I got a good photograph of that diminutive “mountain system.”

After coming down from Hogback we walked a mile out of our way to visit a pond, formed by the damming of Pumpkin Seed Creek. There was an irrigating outlet with plenty of cold, clear water, and my merry plunge

into this, head first, just to feel the soothing touch of cold water, will linger

in my memory as one of the summer’s most delightful incidents.

Few mammals were observed in Banner County. I did not hear a coyote. The thirteen-striped gopher was fairly common on the plains,

but not in the valley, though one or two specimens were seen there. One was observed

during our drive from Kimball, standing up to a head of Oreochara and eating the seeds. Chipmunks were seen occasionally

in the canyons. The only prairie dog settlement observed was within a quarter of a

mile of Harrisburg, and was not extensive. While visiting visiting 3d Canyon one day Dr. Wolcott and I spent some time quietly collecting a species of leaf-eating beetle, feeding

on low bushes growing in a ravine. We had reached a point where the bushes were quite

thick, when we heard something moving near by and saw the bushes shake slightly. While

we were watching to see what had caused it we heard a meow! not at all unlike that

of an ordinary back-yard cat, and at our first step forward at full-grown and fluffy

wildcat burst into the open and headed up the canyon at a terrific rate. I followed

as hard as I could go, but with my own full consent to stop forthwith if the wildcat

should do so. However, It was too badly scared to tarry, and my only reward was a

fleeting glimpse or two of the animal as it rounded the turns of the canyon far ahead.

We tried to find its den, or lair, or whatever it is that wildcats affect for domestic

purposes, but a careful search along the canyon for some distance was without result.

But we had seen a sure-enough bobcat, in perfect working order, and we were much gratified.

Nest of….

36

37

Agriculturally, this seems to be a region of great disappointments. Twenty years ago

there were many efforts to cultivate crops, and wherever we went in the valley the

sites of old-time fields were encountered. Such corn as we saw growing presented a

poor, half-starved appearance, and everyone we interviewed conceded that it was a

hazardous venture to plant crops – simply “a gamble to get back one’s seed,” as one

farmer stated. I had occasion at various points in the valley to dig out tunnels of

Lycosid spiders, and uniformly the soil was dry and dusty as far as I dug – sometimes

fifteen inches at least. Hail is destructive to crops every season. There is not a

railroad in the county – not even a projected road, one native advised me, rather

boastingly, I thought. There are practically no gardens in the region, and such as

there are must be coaxed along with water from wells. Nor does it appear to be much

of a stock country; from the heights we could observe with our binoculars the minutest

detail in the valley for many miles, and very few cattle or horses were visible. Doubtless,

however, we visisted the region at its very worst, for the season was exceptionally

dry, and it is not unlikely that observations during a normal summer would lead to

a more favorable impression of the country.

The general health of the people is good. Dr. Page said that there were very few infections diseases, and that his practices was confined

in the main to “heart” cases – for even this trifling altitude affects many – and

to trouble with the eyes, etc. There are practically no pulmonary affections.

As may be imagined, events and people move very slowly there, and it was not entirely

clear how even so limited a population makes a “living” – as it must be called. But

they have their excitements. A live horse-thief was captured while we were there.

The botanists were absent at the time, and I wondered which they had got; but both

showed up at meal-time.

Nesting colony of….

38

39

The stage picked us up – what was left of us – at a point about ten miles northeast

of Harrisburg, at three o’clock in the afternoon (August 7th). The road through the ridge defining

the north boundary of the valley lay through rough country with buttes and pines.

From the ridge the country north was visible for a great distance, and the green aspect

of the valley of the North Platte River, due to the beneficent effect of extensive irrigation projects, was a restful sight

after our sojourn in a dusty gray valley. The road down the north side of the ridge

was steep and rough, but after reaching comparatively level country it led through

a region with good crops – corn and alfalfa and various grains. The excellence of

an irrigated country is always accentuated to an absurd degree by its sharp contrast

with the surrounding wastes.

Scotts Bluff is a house divided. The radicals write it Scottsbluff; the conservative adhere to

Scotts Bluff. The name appears on signs everywhere, generally in the radical style;

for the Government has much influence locally, and in its wisdom it prescribes the

telescoped form of the name. Being an outsider, and choosing my own point of view,

I lined up with the conservatives, waiting until Newyork and Grandrapids and Sanfrancisco

and Saltlakecity shall have writ their titles so and established a precedent worth

while. But even “Scotts Bluff” is bad form. Scott lived an moved and has his being

in this region many years ago, but in the fullness of time and under stress of circumstances

he laid him down and died on top of the bluff, which was later named in honor of his

bones. He has every right to the dignity of an apostrophe in the name of his graveyard;

but I have never seen it so written on any map or in any list.

Scotts Bluff is noted chiefly on account of its irrigation projects, of course; it

is not so noted, but equally notable, on account of its mosquitoes, which follow irrigation

ditches as the night the day. Citizens who write it Scotts Bluff Admit guardedly that

there are some mosquitoes; citizens who write it Scottsbluff deny that there is a

mosquito in the county; and both classes have their porches and windows screened to

the limit. I have never visited any town, except along the Gulf Coast, where such

unanimity prevailed in the use of mosquito-bar wire netting.

We found the botanists well fed and happy, but loaded down with social obligations

and haircuts and such encumbrances. It was sad to note how civilization had once more

got them hooked and subjugated.

The Doctor and I had only a day and a half in this place, and did not investigate

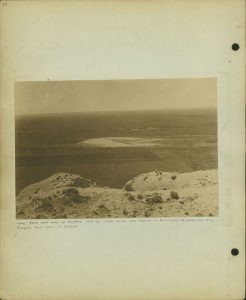

the region very enthusiastically. I took a walk in a southwesterly direction, out

to the edge of things, and photographed Mr. Scott’s bluff – which is across the river

and several miles away from the town.

A view of Scottsbluff, near Scottsbluff, Scotts Bluff Co…..

40

Limited areas in this region are given over to “bad lands” similar in character to

those we had studied in Sioux County.

Dr. Wolcott had gone in the other direction, down the river, and when he returned he “had one”

to tell on himself. He was collecting insects in a field of alfalfa, using his net,

when a farmer came up to see what it was all about. The Doctor replied to his questions,

to the effect that he was collecting insects to see what kinds there were on the alfalfa.

The farmer offered no comment until he had watched proceedings for some time; but

he remarked, as he turned away at last, “Well, that’s the damnedest thing I ever see

a man do!”

We got away from Scotts Bluff on the morning of August 9th. Reaching Bridgeport the Doctor and I parted company with Pool and Williams, who went to Colorado for a vacation – fancy that, now! – while we went north for

further investigations in Sioux County.

41

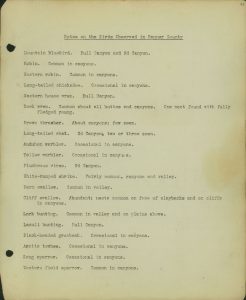

Notes on the Birds Observed in Banner County

- Mountain bluebird. Bull Canyon and 3d Canyon.

- Robin. Common in canyons

- Western robin. Common in canyons

- Long-tailed chickadee. Occasional in canyons.

- Western house wren. Bull Canyon.

- Rock wren. Common about all buttes and canyons. One nest found with fully fledged young.

- Brown thrasher. About canyons; few seen.

- Long-tailed chat. 3d Canyon; two or three seen.

- Audubon warbler. Occasional in canyons.

- Yellow warbler. Occasional in canyons.

- Plumbeous vireo. 3d Canyon.

- White-rumped shrike. Fairly common, canyons and valley.

- Barn swallow. Common in valley.

- Cliff swallow. Abundant; nest common on face of claybanks and on cliffs in canyons

- Lark bunting. Common in valley and on plains above.

- Lazuli bunting. Bull Canyon.

- Black-headed grosbeak. Occasional in canyons.

- Arctic towhee. Occasional in canyons.

- Song sparrow. Occasional in canyons.

- Western field sparrow. Common in canyons.

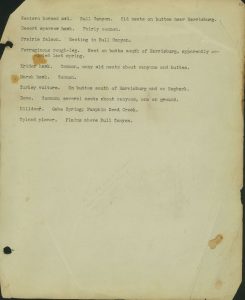

42

- Western chipping sparrow. Common in canyons.

- Western lark sparrow. Common in valley and canyons.

- Western vesper sparrow. Common in valley.

- Western goldfinch. Occasional in canyons.

- Crimson-fronted finch. Bull Canyon; old and young; fully a dozen specimens. New species for Nebraska bird-list.

- Brewer blackbird. Pumpkin Seed Creek; Long Spring.

- Western meadowlark. Common in valley.

- Redwing. Pumpkin Seed Creek.

- Cowbird. Young being fed by rock wrens, 3d Canyon; mature female seen in vicinity.

- Magpie. Common in canyons; several old nests.

- Desert horned lark. Abundant. Old nests common in valley.

- Trail flycatcher. Common in canyons. Full-grown young.

- Western wood pewee. Bull Canyon.

- Say phoebe. Common, making life miserable for Krider hawks. Nests found about ledges in canyons and in outbuildings of the valley.

- Arkansas flycatcher. Common. Full-grown young.

- Kingbird. Fairly common, associating with Arkansas flycatcher.

- Broad-tailed hummer. One seen, 3d Canyon.

- Red-shafted flicker. Common in canyons.

- White-throated rock swift. Common about cliffs, 3d Canyon, Bull Canyon, Hogback Mountains. Full-grown young. Old nesting sites examined.

- Western nighthawk. Common in valley.

- Kingfisher. One seen at irrigating pond on Pumpkin Seed Creek.

- Burrowing owl. Several about prairie-dog town near Harrisburg.

43

- Western horned owl. Bull Canyon. Old nests on buttes near Harrisburg.

- Desert sparrow hawk. Fairly common.

- Prairie falcon. Nesting in Bull Canyon.

- Ferruginous rough-leg. Nest on butte south of Harrisburg, apparently occupied last spring.

- Krider hawk. Common, many old nests about canyons and buttes.

- Marsh hawk. Common.

- Turkey vulture. On buttes south of Harrisburg and on Hogback.

- Dove. Common; several nests about canyons, one on ground.

- Killdeer. Gabe spring; Pumpkin Seed Creek.

- Upland plover. Plains above Bull Canyon.