Great Nebraska

Naturalists and Scientists

Frank H. Shoemaker

Thomas County, July 3-11, July 27-30, 1911

cover

cover

titlepage

135 N 14th St.

Lincoln, Nebraska

Frank H. Shoemaker

P.O Box 3

Lincoln, Nebraska

II. — Thomas County, Nebraska Forest Reserve Station, near Halsey) July 3-13–27-30, 1911

map

map

1

Our party in Thomas County was reduced to Profs. Pool and Williams, Dr. Wolcott, and myself. Mr. Dawson stopped over for two days to look into the status of the pine-tip moth, when he returned

to Lincoln. Mr. Leussler had left Sioux County two days ahead of our party, to resume his duties in Omaha. We reached Halsey on the morning of July 3rd and remained there until the 13th, Dr. Wolcott, however, returning to Lincoln for several days during this period. Our first trip to Cherry County occupied the time from July 14th to 26th, when we again returned to Halsey and remained from July 27th to 30th.

for several years, General Manager)

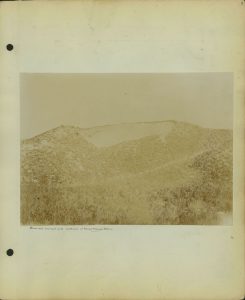

The Forest Reserve Station

is two and a half miles west of Halsey, In the valley of the Middle Loup River. The river runs through sandhills, and the valley is rather restricted, being at

no point in this region more than a mile or two miles in width. The valley is fertile

and contains some good “ranches” — a perverted term, applied indiscriminately to anything

from a half-acre truck garden to a ten-section cattle range.

The Station is provided with very good buildings, and at present time about fifteen men conduct the experimentation, which is an effort to “reclaim“ a portion of the sandhills by the planting of pine trees of various kinds. If these

can be induced to grow, the shifting sand will be held in place, minor vegetation will have a chance to gain

a foothold, the decay of this vegetation will form humus, and ultimately a soil of

sufficient depth will cover the surface to resist the action of the wind. The experiments

have been (1911)carried on now (1911) for nine years, and in many ways have proven successful; but the progress is necessarily

slow, and it has not yet been determined whether the effort, as a whole, will be a

success.

One factor of great importance, however — a condition which has been brought about

by settlement of the country — is the limiting of prairie fires to comparatively small

areas. Before the country was settled these fires were of very common occurrence

and of great extent, resulting in the undoing almost yearly of all that Mother Nature

had done to reclaim these wastes at her own instance. The vegetation was swept away

by the fires, the winds carried every vestige of ashes and unconsumed materials to

the ends of the earth, and the sand, having nothing to hold it in place, was drifted

about by the millions of tons. Now, with fires now greatly reduced in frequency and confined to much smaller areas by cultivation, by

the grazing of large tracts and the consequent reduction of dry, dead grass, and by

persistent fighting when they do start, the region is being given a much better opportunity

to mend itself, and the pine-planting experiment as an additional aid is quite reasonable

and commendable. It is easy to criticize efforts which do not yield immediate results,

and the Halsey venture is one of these.

There are many things which favor the effort, chief among these being the fact that

moisture is held by the sand in wonderful amount; even in the “blow-outs,” to be described

later, where the sun beats down fiercely and the radiated heat is terrific, there

is generally abundant moisture a few inches below the surface. If, then, a means is found of holding the sand in place — even a shallow surface soil — the

productiveness

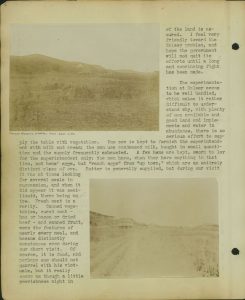

Forest Reserve Station, from east side

2

of the land is assured. I feel very friendly towards the Halsey problem, and hope the government will not quit its efforts until a long and convincing

fight has been made.

The experimentation at Halsey seems to be well handled, which makes it rather difficult to understand why, with

plenty of men available and good land and implements and water in abundance, there

is no serious effort to supply the table with vegetables. One cow is kept to furnish

the superintendent with milk and cream; the men use condensed milk, bought in small

quantities and the supply frequently exhausted. A few hens are kept, sworn to lay

for the superintendent only; the men have, when they have anything in that line, not

hens’ eggs, but “ranch eggs” from “up town,” which are an entirely distinct class

of ova. Butter is generally supplied, but during our visit it was at several times

lacking for several meals in succession, and when it did appear it was semi-liquid,

there being no ice. Fresh meat is a rarity. Canned vegetables, cured meat – ham

or bacon or dried beef – and canned fruit, were the features of nearly every meal,

and became distinctly monotonous even during our short visit. Of course, it is food,

and perhaps one should not quarrel with his victuals, but it really seems as though

a little peevishness might in

… east side

….

3

this case accomplish something, when cows and chickens and a garden and ice could

be cared for and profited by without adding to the force of the men, and furthermore

would almost certainly effect a considerable saving in the year’s table expenses.

When we went to get cots from the second floor of the bunk house we found dozens of

Cimex lectularia [cimex lectularius, common bedbug] executing maneuvers in the folds thereof. Fortunately,

it is their nature to react negatively to light, and a thorough sunning of the cots,

aided by microscopically

careful manual extraction, resulted in the possession of usable beds, which we moved

far away. A tent was furnished us and we set it up midway between the main building

and the bunk house. I slept there for a night or two, but it did not appeal to me

very strongly, as I prefer to take my fresh air straight; so I hied me to the hills,

having acquired a penchant for sky bed-rooms

View….

View….

4

while Sioux County. A fine hill back of the station suited my fancy, and there I wasted many hours

in sleep.

One of the real joys of our Forest Reserve experience was the bathing in the river.

The volume of water is considerable, and the fact that we could rarely find places

over three feet deep did not detract from the cool delight of fighting the swift current.

I indulged in a swim at all kinds of hours, even at midnight, the invitation of the

water being especially tempting after a hot trip in the sandhills.

As will be noted from the accompanying photographs, the region hereabouts is divided

sharply into just two kinds of country — the sandhills and the valley. The sandhills

are high and rugged, covered in the main with “bunch-grass,” with here and there areas,

generally on slopes or in depressions, thickly covered with shrubs. There are enough

suitable grasses that it is a good grazing country.

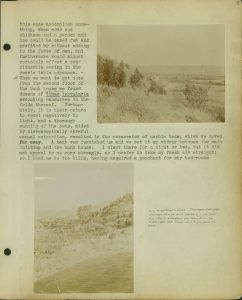

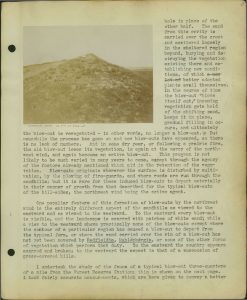

The most striking and characteristic things about the sandhill country are the “blow-outs.”

Great hills of sand are attacked by the northwest winds, which in the course of years

excavate large cavities, beginning at the vulnerable point near the crest and working

down and backward, so that finally the one-time hill becomes but half a hill with

a deep

…

5

hole in place of the other half. The sand from the cavity is carried over the crest

and scattered loosely in the sheltered region beyond, burying and destroying the vegetation

existing there and establishing new conditions, of which better adapted plants avail

themselves. In the course of time the blow-out “blows itself out,” incoming vegetation

gets hold of the shifting, keeps it in place, gradual filling in occurs, and ultimately

the blow-out is revegetated – In other words, no longer a blow-out.

But meanwhile the process has gone on and new blow-outs have appeared, so there is

no lack of numbers. And in some dry year, or following a prairie fire, the old blow-out

loses its vegetation, is again at the mercy of the northwest wind, and again becomes

an active blow-out. This program is not likely to be much varied in the many years

to come, except through the agency of the factors already mentioned which aid in the

retention of the vegetation. Blow-outs originate wherever the surface is disturbed

by cultivation, by the plowing of fire-guards, and where roads are run through the

sandhills; but it is rare for these induced blow-outs to depart materially in their

manner of growth from that described for the typical blow-outs of the hill-sides,

the northwest wind being the active agent.

One peculiar feature of this formation of blow-outs by the northwest wind is entirely

different aspect of the sandhills as viewed to the eastward and as viewed to the westward.

To the eastward every blow-out is visible, and the landscape is scarred with patches

of white sand; while a view to the westward shows practically none of the blow-outs

except where the contour of a particular region has caused a blow-out to depart from

the typical form, or where the sand carried over the rim of the blow-out has not yet

been covered by Redfieldia [grass genus], Muhlenburgia [muhlenbergia, grass genus] or some other forms of vegetation which perform that

duty. To the eastward the country appears scarred and broken; to the westward the

aspect is that of a succession of grass-covered hills.

I undertook the study of the fauna of a typical blow-out three-quarters of a mile

from the Forest Reserve Station

; this is shown on the next page. I took fairly accurate measurements, which are

here given to convey a better

…

6

…

7

idea of blow-outs of which this one is a fair example, slightly larger than usual,

but exceeded in size by many. From A to B the distance is 156 feet; from C to D 131

feet. The approximate depth from the highpoint A to the bottom, not visible in the

photograph, is 70 or 80 feet. The circumference around the rim is 403 feet. The

photograph on page 8 shows the northwest “corner” of the blow-out with the characteristic

caving in of that part.

I have not yet studied the insects taken in this blow-out, but was surprised during

the period of collecting at the great variety found, for it was not a salubrious place.

Observations made by Prof. Pool (not in this blow-out, but in one very similar, shown on page 9), during the hot

part of the day, when most of my collecting was done, showed just above the sand temperatures

of 145, 147, and 148 degrees, though the general temperature outside was quite comfortable

– say somewhere down in the nineties.

Over the rim of the blow-outs, sometimes running up to the crest, but ordinarily beneath

a zone claimed by grasses, there is almost invariably found a slope well covered with

poison ivy. It is one of the most persistent and pernicious plants of this region,

and total acreage of these handsome, thriving, rascally, three-leaved outlaws must

be tremendous.

The grasses of this region are naturally of particular interest, since they constitute

the economic foundation of a grazing country, and I should like to give here some

definite information concerning the species found and their distribution. But though

I collected specimens of grasses throughout the summer, and have a fair representation

of the species found in the western parts of the state, I have not yet classified

the collection. This field of investigation, of course, belonged to the botanists,

and was fully covered by them, my collecting in this line being undertaken simply

for my personal information and satisfaction.

…

8

…

9

…

10

…

11

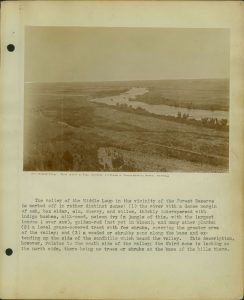

The valley of the Middle Loup in the vicinity of the Forest Reserve is marked off in rather distinct zones: (1)

the river with a dense margin of ash, box elder, elm, cherry, and willow, thickly

interspersed with indigo bushes, milk-weed, poison ivy (a jungle of this, with the

largest leaves I ever saw), golden-rod (not yet in bloom), and many other plants;

(2) a level grass-covered tract with few shrubs, covering the greater area of the

valley; and (3) a wooded or shrubby zone along the base and extending up the side

of the sandhills which bound the valley. This description, however, relates to the

south side of the valley; the third zone is lacking on the north side, there being

no trees or shrubs at the base of the hills there.

The accompanying list of birds seen during our visit here is in no way remarkable.

Two species are put down questionably – the desert horned lark and the goldfinch; these may be instead the prairie horned lark and the western goldfinch.

…

12

…

13

…

14

…

…

15

16

List of Birds seen in Thomas Co., Nebr., July 3-11, 27-30

- Great blue heron

- Baird sandpiper

- Spotted sandpiper

- Killdeer

- Bobwhite

- Prairie hen

- Mourning dove

- Marsh hawk

- Sparrow hawk

- Short-eared owl

- Burrowing owl

- Yellow-billed cuckoo

- Black-billed cuckoo

- Belted kingfisher

- Sennett nighthawk

- Kingbird

- Northern flicker

- Desert (?) horned lark

- Blue jay

- Cowbird

- Red-winged blackbird

- Western meadowlark

- Orchard oriole

- Goldfinch

- Western vesper sparrow

- Western lark sparrow

- Western field sparrow

- Chipping sparrow

- Arctic towhee

- Western blue grosbeak

- Dickcissel

- Lark bunting

- Barn swallow

- Bank swallow

- Yellow warbler

- Western yellowthroat

- Long-tailed chat

- Catbird

- Brown thrasher

- Bell vireo

In the late afternoon of July 7th, I was enjoying my usual evening walk along the

outer edge of the border of trees skirting the river, and had reached a point half

a mile from the Forest Reserve Station

, when my attention was attracted by persistent alarm notes of the Bell vireo, one of the very common birds in the bushes along the river. I made my way through

the plum thicket, and, guided by the calls, had no difficulty in finding the nest,

containing young birds, with both parents fluttering about in great excitement.

The nest was well out on a branch, suspended in the usual way between diverging twigs,

not over two feet from the ground. I expected to find a blue jay responsible for the disturbance, but instead it proved to be a bull snake, which

I did not at first see, as it was in the branches above and several feet away from

the nest. The snake had evidently observed my approach, and was absolutely motionless,

except for the playing of its tongue. I settled very slowly, so as not to alarm the

snake, to an easy position with one knee on the ground, and awaited developments.

The birds were so overwrought by the menace of the snake that the lesser calamity

of my insignificant self by their nest did not bother them, and they perched several

times on twigs within two feet of my face, devoting all their vocabulary to the bull-snake.

Other birds joined in. A long-tailed chat perched only four feet from me, wrinkled his brow, made several irrelevant remarks

after the manner of chats, and retired in good order. An orchard oriole appeared, viewed the situation from twenty-seven positions in as many seconds, said

not a word, and passed by on the other side.

Meanwhile, for at least five minutes, the snake did not move a fraction of an inch;

tense and watchful, with the head and several inches of its body held well away from

the branch about which it was twined, it

17

devoted all of its attention, until the “memory” wore away, to the large object which

had suddenly moved into the region, but which, after all, was probably harmless; then

it slowly doubled back on itself, darting its tongue — a most delicate organ of touch

– here and there to pilot its way safely, and started down the branch.

Reaching the body of the tree, which was in fact only a shrub, not over six or seven

feet high, it descended with great deliberation, finally reaching the branch on which

the nest was placed. Here it paused for a moment, then started out along the branch.

Several inches from the trunk it encountered the top leaves of weeds which extended

up into the lower branches of the tree, and thrusting it’s head on these it tried

their strength; but they were weak and flexible and would not support it’s weight,

so that course was abandoned for the more rigid branch. Slowly the snake crept along,

until finally the nest was reached and the sensitive tongue touched its rim.

Up to this time the entire behavior of the snake had been deliberate; no rapid movements,

no hurried exploration of branches. But now a stimulus was encountered which very

plainly was not unknown to the snake; with a rapid movement, almost a jerk, it raised

its head several inches above the nest, opened wide its jaws, and struck! . . . Really,

that is all there is to the story, for the snake’s conduct, not mine, is the subject

of these notes; but in my capacity as referee I may add a few words. Being, if you

please, quite as highly organized and functioned as an ordinary bull-snake, it came

to pass that even as the snake struck down upon the defenseless heads of the baby

vireos, I grasped the reptile amidships and hauled in enough slack that the blow fell short

of the nest. That is all. The subsequent court-martial and execution have no place

in this narrative.

The power of vision in snakes is so poor that probably its sole function, aside from

the appreciation of light itself, is the perception of motion. From the standpoint

of the snake, if a moving object be large, it is a good thing to get away from, just

for luck; whereas if it be small it may be good to eat, and at any rate is worth following

up, since there is no danger. There is evidently not the slightest appreciation of

form. Snakes in captivity, hungry after long fasting, if a toad is introduced into

their midst, will go after it with much ardor, when, if the toad is active, and by

its movements continually discovers its whereabouts to the pursuers, it will be promptly

overtaken and will pass into the “sad pluperfect”. But if the toad is inactive or

distrait, [absent-minded, distraught] and sits moodily awaiting the fell summons,

the snake will pass it time and again within a few inches, though hunting as hard

as they know how. But the slightest movement is fatal; and it is also fatal if, even

though motionless, the toad is touched by a blundering snake with the wonderful tongue

— a tactile organ muscled and nerved with marvelous delicacy and beauty. — These

observations are so common among those who have taken the trouble to note them that

it is hardly worthwhile to put them down, except for their bearing on the incident

of the vireo’s nest. There is hardly a shadow of probability that the snake saw the nest from the

ground and went up after it, or that any snake ever saw a nest in the tree, or a foot

from its eyes. Snakes of many species ascend trees habitually in search of food,

and cover great distances along the branches, finding, as we all know, many nests,

…

…

18

and devouring the young or eggs, doubtless in many cases capturing even mature birds.

The behavior of this particular snake, when going out upon the branch where the nest

was located, was not at all indicative of purposive action; it even tried to take

another route, which proved impracticable. Not until it actually touched the nest

did it know of its proximity, and there is every reason to believe that its discovery

was entirely by chance, and that every nest found by snakes is so.

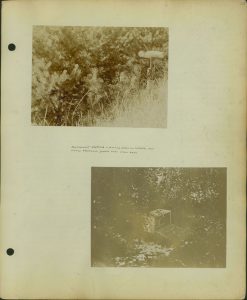

I tried on July 9th to take several photographs of the vireos feeding the young, but in my anxiety to guard against a blurred image on account of

movement, I went to the other extreme, and all my plates were underexposed. One barely

passable photograph is shown. I had supposed the nestlings to be younger than they

proved. I settled down by the nest, about six feet away, and was accorded scant attention

by the parent birds, though they had indignantly drummed me out of camp after the

snake incident. I remained there for more than an hour. Both birds were feeding

the young. The food brought consisted of numbers of larvae, green and brown and of

assorted sizes; katydids, small beetles, and a large horse-fly. If the young bird

had trouble in swallowing the food the parent bird assisted, poking away vigorously

until the mouthful was well on the way down. On one occasion a large insect was given

to one of the young, which did not lay hold with relish, so the insect was taken away

and given to another youngster. While I was watching, one of the young birds laboriously

extricated itself from the nest, perched on the edge,

…

19

took the next consignment of provisions, and then struck out into the big world, up

the same branch the bull-snake had used. It perched very readily, maintaining its

equilibrium perfectly; it cleared spaces of six to eight inches in its jumps from

twig to twig, but on one of these daring leaps saved itself only by hanging on with

its “chin” while it fluttered its wings and clawed desperately for a foothold. The

others were not impressed by the actions of the venturesome one, and remained quietly

in the nest. They were well feathered, and surprisingly alert, often indicating by

their actions that they sensed the approach of one of the parent birds before I myself

had seen or heard it.

The next morning the nest was empty, and the little ones were widely scattered among

the trees and bushes. Guided by their baby notes, I had little difficulty finding

all four, and kidnapped two of them for a final picture. It would have been very

nice to have photographed all four, strung along a branch; but the handling unaided

of even two was a large order, and the accompanying photograph was obtained only after

a half dozen trips into the bushes in pursuit of the runaways, who objected seriously

to even 1/100-second inactivity.

Western grasshopper sparrows were abundant, and numerous nests were found containing eggs or young, while several

young birds were seen flying about. One nest containing four young, admirably situated

for photography, was marked for that purpose when the young should have become slightly

more developed and interesting. When I visited the nest two days later, the nest

was empty.

Dickcissels were nesting in the scattered bushes of the valley, and several nests were found.

My attention was drawn to one nest by the flight of a cowbird from it. The nest was in a very small bush, only eight inches from the ground, and

had been pulled out of shape, so that one edge was very low. One young dickcissel, about four days hatched, was in the nest, and another on the ground, apparently

having been kicked out by the cowbird. There was also one egg of the dickcissel, apparently

…

19

infertile, and an egg of the cowbird, doubtless laid by the bird I had seen leaving the nest, as it proved to be perfectly

fresh. My means of ascertaining its freshness, I do not scruple to confess, or rather

boast, was the simple expedient of busting it open. Whatever may be said of the unwisdom

of molesting the processes of Nature’s ordained plan, I draw the line just short of

the cowbird, considering her definitely without the pale, and one of Nature’s worst blunders.

When I find cowbirds’ eggs in a nest they come out, and I flatter myself that I have saved hundreds of

young birds, of dozens of species, by removing these false gems. I did a little job

of carpentering, shoring up the nest to a proper level, adding a scantling or two

and repairing the wainscoting, replaced the fallen infant and went on my way. — It

is unusual for the cowbird to deposit an egg with young birds so far developed. —

Four days later the nest was found again pulled far down at the side, and the young

birds were gone.

Young orchard orioles were flying about in the bushes near where the vireo’s nest was found. I stalked

one little fellow and caught him in my butterfly net, for the sake of a visit.

I copy a very unscientific note from my field book, under date of July 10th, just

as it stands: “Caught a mouse this morning in the upstairs

room where we keep our things, and chucked it from a small box into a pail of water.

Suddenly remembered that I had nothing against the mouse, and dropped it a tissue-paper

rope, up which it promptly shinned and sat shivering on the rim of the pail, while

I stood there ashamed of myself. I essayed to stroke its head with a finger-tip and

it sat still; so I took it in my hands and warmed it up. Then I held it near the floor

and tried to push it out of my palm with my thumb, but it ran around the thumb and

signified its preference to remain in the warm quarters. So I babied it while and

finally pushed it off, whereupon it faded promptly into the ample hole through which

the water pipes pass.” — And while I am on the notes for July 10th, here is another

…

…

21

…

22

…

23

extract: “Started out this afternoon for the sandhills — my pet blow-out — but had

gone only about 200 yards from the front gate when I found a large lycosid [member of lycosidae, wolf spider, family] tunnel” — the Lycosids are in the main tunnel-inhabiting spiders — “and stopped to take photographs. Various

methods of coaxing the spider out were tried, but she would not come, though she struck

viciously at a straw thrust a few inches below the entrance. At this juncture a wandering

Pasimachus [genus of ground beetle] ” —

this is a large black beetle — “came by, and I put him down the hole. There was something

doing at once, and when Pasimachus returned to the surface he evinced a liking for tall and distant timber; but I waived

his preference and put him down again. Several efforts of this kind got the lycosid

so excited that she came rushing out at last, and I took her photograph.” This tunnel

on excavation proved to be only four inches in extent, which is unusually short.

I do not say much about spiders in these notes, but throughout the summer they came

in for much attention, and I collected hundreds of specimens from every imaginable

location — from tunnels, holes in the ground, webs between twigs or grasses or flowers,

from the summit of bare buttes, from blow-outs, from the surface of ponds, from concealment

under logs or stones; many of them were swept from vegetation by means of a net or

beaten from pines and cedars or from deciduous trees in the various regions which

we visited. The spiders of Nebraska have not been studied,

and it was my aim to get together a collection for classification during the winter.

So between remarks about other things there might appear much about spiders, were

it not for the fact that I have concluded to eliminate such notes for the sake of

brevity, though in the midst of all these pages the statement is unconvincing.

Teddy is venerable Maltese cat who has for many years held an honored position on

the Forest Reserve staff. One night Teddy had a battle, which disturbed the men who

were sleeping outside the quarters, as several of them prefer to do, and on investigation

they found that Teddy’s opponent was a weasel. Teddy was the victor after a hard fight,

and later in the day donated the skin

…

24

25

…

25

to me and viscera [entrails] to the University for the class in parasitology. Weasels

are said to fairly common here. This specimen was in the usual summer pelage — the

body soft brown above and white beneath.

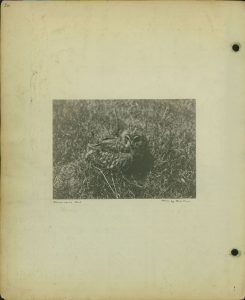

On July 12th there was a violent hail — and rain-storm at 4:30 p.m. Over an inch and

a half of rain fell within a few minutes. The hail did very great damage to crops,

the leaves being entirely stripped from corn and the bare stalks bent over flat upon

the ground by the violent northwest wind. There had been other rains during the month

and the result was such an unusual amount of moisture that Prof. Pool’s investigations regarding soil moisture were seriously interfered with, the month

being abnormal in this regard. Many birds were killed by the hail. Italians working

on the railroad at Halsey were said to have found large numbers of dead prairie chickens, but I was unable to learn the facts. On the 13th Profs. Pool and Williams brought in a short-eared owl with a broken wing, doubtless a victim of this storm. I was busy with facsondence

and had no time to photograph the bird, but Prof. Pool got a good picture, which is shown herewith. The bird was released among the pins,

with a prayer that he and Teddy might not meet. There was abundant food, and

…

26

…

…

27

the wing might heal; at least, this was the reasoning we indulged in to avoid the

painful alternative of killing the bird.

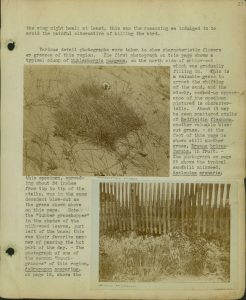

Various detail photographs were taken to show characteristic flowers or grasses of

this region. The first photograph on this page shows a typical clump of Muhlenbergia pungens, [sandhill muhly, grass] on the north side of a blow-out

which was gradually filling in. This is a valuable grass to arrest the shifting of

the sand, and the stocky, combed-up appearance of the specimen pictured is characteristic.

About it may be seen scattered stalks of Redfieldia flexuosa, [vasey, blowout grass] another valuable blowout grass. — At the foot of this page

is shown still another grass, Bromus brizae formis, in fruit. — The photograph on page 25 shows the typical sandhill milkweed, Asclepias

arenaria; [whitestem milkweed] this specimen, spreading about 24 inches from tip to

tip of the stalks, was in the same decadent blow-out as the grass shown above on the

this page. Note the “lumber grasshopper” in the shadow of the milk-weed leaves, just

left of the base; this was their favorite manner of passing the hot part of the day.

— The photograph of one of the common “bunch grasses” of this region, Andropogon scoparius, [little bluestem] on page 19, shows the

…

28

character of this grass, and also the nesting site of a western grasshopper sparrow; the nest, not visible in the photograph, was deeply set in the central clump. –

On page 20 is a picture of a pretty little spreading plant (Euphorbia sp.) with minute

white flowers, which is very common throughout the sandhills. — The photographs on

pages 21 and 22 show the common cone-flower, Ratibida columnaris, [yellow prairie coneflower] with a common plantain, Plantago purshii, [woolly plantain] in the foreground. Note the longicorn beetle (Typocerus sp.) [insect species] on the central flower in the photograph on page 22; these were

abundant, and showed remarkable variety in the elytral [fore wing on insect] markings.