Great Nebraska

Naturalists and ScientistsJanuary 6, 1937

1937

Jan 6 Scottsbluff, Nebraska

. . . . It seems that someone was trying to get me to consider the absurd idea of entering a car, to be taken to a hospital. “Hospital?” I repeated dully; “no, thank you; I’m not hurt.”

Night was just setting in. Somehow, I had no sense of my placement; I was on the edge of a highway somewhere, and a street light was blazing almost overhead. My head did not ache, but there was an unaccustomed ringing inside it. For some reason not clear, a man had his arms affectionately about my waist, and two or three others were standing by. – My soft hat did not seem to fit properly, so I reached up to place it comfortably; and with my hands this raised I chanced to get a look at my upper left arm.

A raw red mass it was, pulsing blood, with dripping rags suspended from it, jagged and hacked as though cut with very dull shears; the torn cloth was nicely dusted over, and pieces of dead weeds were sticking out of the flesh like skewers. Viewing this evidence, it seemed pedantic to longer insist that I had not been hurt; the sensing of the fact that I somehow had been injured, however, brought to me no shock. I clearly remember that my viewing of the bad wound was quite impersonal, and that my interest was devoted entirely to the surgical procedure indicated. – Strangely, I remember precisely what I said:

“Well, I guess I am hurt a little.”

As I was bleeding profusely from several scalp wounds, the blood oozing out under my hat-band and selecting tangents across my cheeks, all unknown to me, this admission must have afforded my listeners an impressive example of under-statement.

I was conducted to a car and we rushed to Gering, only a half mile distant: the driver, myself, and a good Samaritan whose name I never learned. Immediately after seeing the flow of blood from the arm wound I had stuck my right hand inside my clothing next to the skin and had used thumb and fingers as a tourniquet; I remember how they ached from the long-continued pressure.

I was asked which of the two Gering doctors I wished to handle the matter. I knew neither personally, but I remembered that one of them I had seldom seen on the street without a cigaret in his face or fingers; so on chance I indicated the other. Contact with this doctor fortunately was prompt, and I began to receive proper attention. The doctor explained, as he did the first things, that the cleaning and stitching would be painful, and that he would give me an anesthetic.

Twenty-eight years before, I had had my sole hospital experience; a burst appendix, peritonitis. I remembered the stultifying and retarding effect upon recovery, of my anesthetic (absolutely necessary in that case); so I told the doctor that, unless he definitely ordered anesthesia, as was his right, I would prefer to consciously stand the pain. He was kind enough to let me have it my way; reassuring me, however, that it would hurt plenty. – As a diagnostician he approached perfection; it did hurt plenty.

I had been quite unaware of a leg injury which was really the most serious of my wounds. The fender of the car which had struck me had crushed an area of the flesh on the outside of my left leg against the femur, amazingly not breaking or even injuring the bone.

After the cleaning and medicament, it took eight stitches to adjust the muscles of my arm, and eight more to patch the skin; a few on the leg injury; another lot on my scalp. Those taken in arm and leg were painful, the scalp stitches hardly so at all. I had firmly made up my mind not to yip; and though incentive to vocalization offered, I managed to take it quietly. – Chance sometimes is O. K.; my doctor had no cigaret aura about him.

Now about how it all happened. It was in the early evening of December 15th. I had been in Scottsbluff, had stopped for a visit with my Terhune friends who have their residence, greenhouse and nursery a mile from Gering business center, and had resumed my walk. When just across the Union Pacific track, on the highway only a hundred yards from the depot, I was hailed by someone in a car bound for Gering; and I recognized the two women in the car as former associates in work on Nebraska Panhandle historical data.

This was in the evening heavy traffic period between Scottsbluff and Gering, one of the busiest short roads in the whole state. The car from which I had been hailed had stopped in the line of traffic instead of pulling out, and was waiting for me. Within a very few seconds a dozen cars were stopped or slowing, and their horns were saying unpleasant but quite righteous things. – For once in my

life I did not take proper care; I rushed out to relieve this ridiculous situation; and I was struck by a car going north, in the near lane. It is interesting to me that I have not the faintest recollection of the car or of its impact; that I have no memory of even the slightest sense of pain.

The fender bumper struck the left side of my left leg, five inches above the knee, as I (going westward) was barely entering the northbound lane; had I been another two or three inches forward it would have broken my thigh bone and probably killed me. The impact must have been with the extreme tip of the fender bumper, and was light enough to rotate my body slightly, and my own impetus was sufficient to thrust me, still upright, against the side of the rapidly moving car; and there I get my arm injury. The horizontal rather acute-pointed car door handle penetrated all of my clothing, ripped the main muscle to the humerus, even parting the thin, bone-clinging triceps, and set me rolling; which accounts probably for most of the scalp injuries, and for the dust and the week skewers imbedded in the torn muscles.

I was wearing, Decemberwise, a heavy mackinaw, a medium weight suit, a shirt, and light underwear; through all of these layers the car door handle passed and ripped the muscles clear to the bone. The doctor told me later that the main nerve of the arm lay exposed for an inch or more on the humerus, untouched!

The driver of the Wyoming car which had struck me came back at once, I remember, and voluntarily gave someone his name, residence,

“Frank,” he said, “I have a whole mess of letters about you; from the Chancellor of the State University; from the Secretary of the State Historical Society, who is also on the teaching staff of the university in history and law; from the Dean of the College of Medicine in Omaha; and others. All these letters were forwarded here to ex-Congressman Mathers, who ran over to my place last night and we looked them over.

“These friends of yours are set in the belief that the place where you belong is in the University Hospital in Omaha; and a great group of papers have come, the filling in and signing of which would regularize and legalize such transfer.

“Now, my own feeling is this: We all know the slow movement of these deadly, formal papers. In my opinion it would be a full three weeks – say about February 1 – before the full legal procedure incident to your placement in the University Hospital at Omaha could be completed.

“And by that time, the way your case is moving, I expect to have you up and about, a ‘going concern’ – probably of necessity at an east pace for a time, but none the less, wholesomely mended.

“Now, how about it? What shall I say to Lincoln and Omaha?”

It did not take me long to adopt the doctor’s view. Had it been possible for the University Hospital to take me over on, say December 16 instead of February 1, doubtless it would have been to my advantage; whereas this proposed belated transfer seems rather meaningless.

However, I do love to dwell upon this splendid friendliness. Because of my past service to the College of Medicine and the University Hospital (where I was in charge of clinical photography, 1927-30), these good friends purpose my placement there for treatment; no question raised as to whether that would mean two weeks or six months. I am appreciative to a degree of this kindly offer.

January 6, 1937

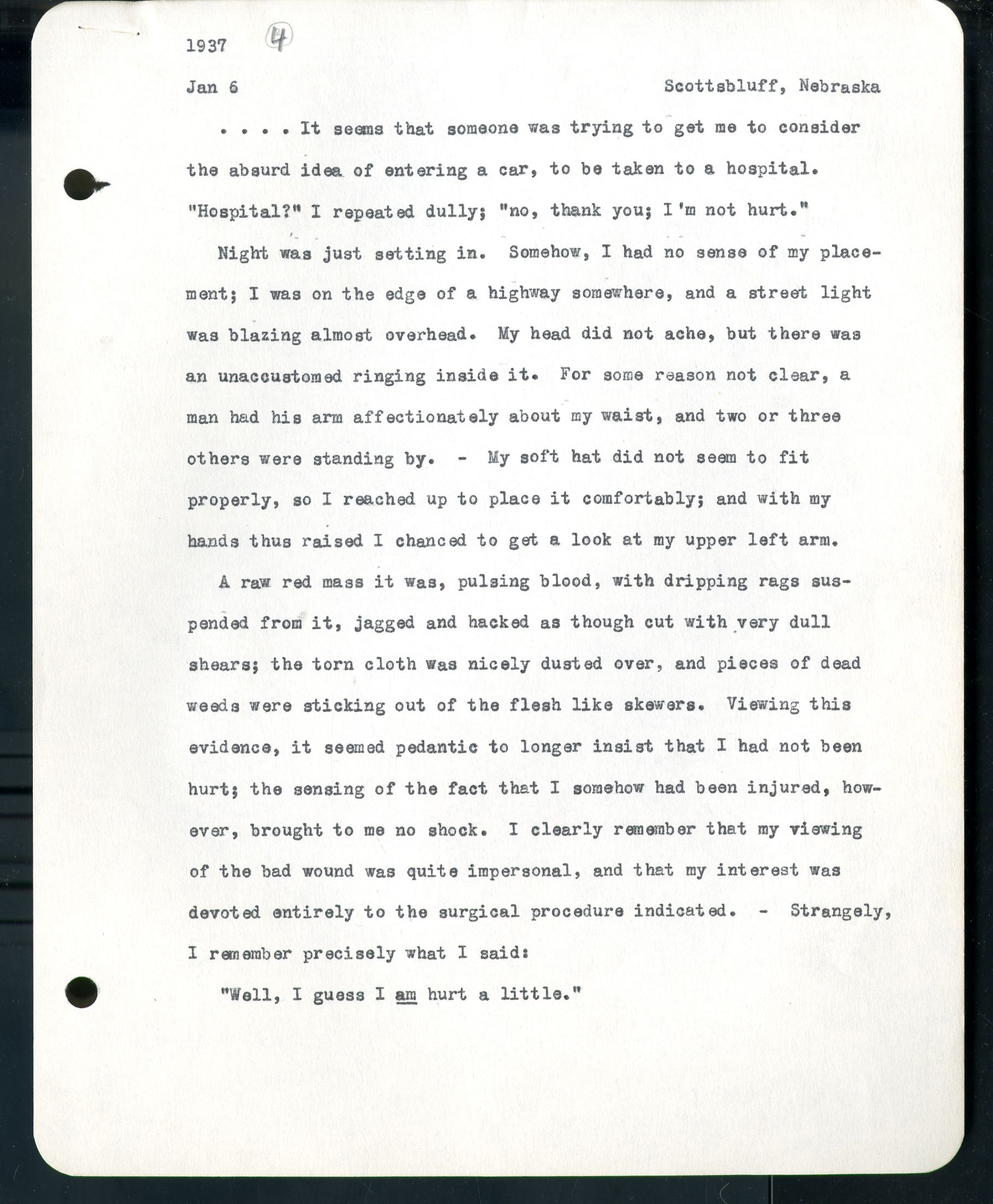

1937 4

Jan 6 Scottsbluff, Nebraska

….It seems that someone was trying to get me to consider the absurd idea of entering a car, to be taken to a hospital. “Hospital?” I repeated dully; “no, thank you; I’m no hurt.”

Night was just setting in. Somehow, I had no sense of my placement; I was on the edge of a highway somewhere, and a street light was blazing almost overhead. My head did not ache, but there was an unaccustomed ringing inside it. For some reason not clear, a man had his arm affectionately about my waist, and two or three others were standing by. – My soft hat did not seem to fit properly, so I reached up to place it comfortably; and with my hands thus raised I chanced to get a look at my upper left arm.

A raw red mass it was, pulsing blood, with dripping rags suspended form it, jagged and backed as though cut with very dull shears; the torn cloth was nicely dusted over, and pieces of dead weeds were sticking out of the flesh like skewers. Viewing this evidence, it seemed pedantic to longer insist that I had not been hurt; the sensing of the fact that I somehow had been injured, however, brought to me no shock. I clearly remember that my viewing of the bad wound was quite impersonal, and that my interest was devoted entirely to the surgical procedure indicated. – Strangely, I remember precisely what I said:

“Well, I guess I am hurt a little.”

As I was bleeding profusely from several scalp wounds, the blood oozing out under my hat-band and selecting tangents across my cheeks, all unknown to me, this admission must have afforded my listeners an impressive example of under-statement.

I was conducted to a car and we rushed to Gering, only a half mile distant: the driver, myself, and a good Samaritan whose name I never learned. Immediately after seeing the flow of blood from the arm wound I had stuck my right hand inside my clothing next to the skin and had used them and fingers as a tourniquet; I remember how they ached from the long-continued pressure.

I was asked which of the two Gering doctors I wished to handle the matter. I knew neither personally, but I remembered that one of them I had seldom seen on the street without a cigaret in his face or fingers; so on a chance I indicated the other. Contact with this doctor fortunately was prompt, and I began to receive proper attention. The doctor explained, as he did the first things, that the cleaning and stitching would be painful, and that he would give me an anesthetic.

Twenty-eight years before, I had had my sole hospital experience; a burst appendix, peritonitis. I remembered the stultifying and retarding effect upon recovery, of my anesthetic (absolutely necessary in that case); so I told the doctor that, unless he definitely ordered anesthesia, as was his right, I would prefer to consciously stand the pain. He was kind enough to let me have it my way; reassuring me, however, that it would hurt plenty. – As a diagnostician he approached perfection; it did hurt plenty.

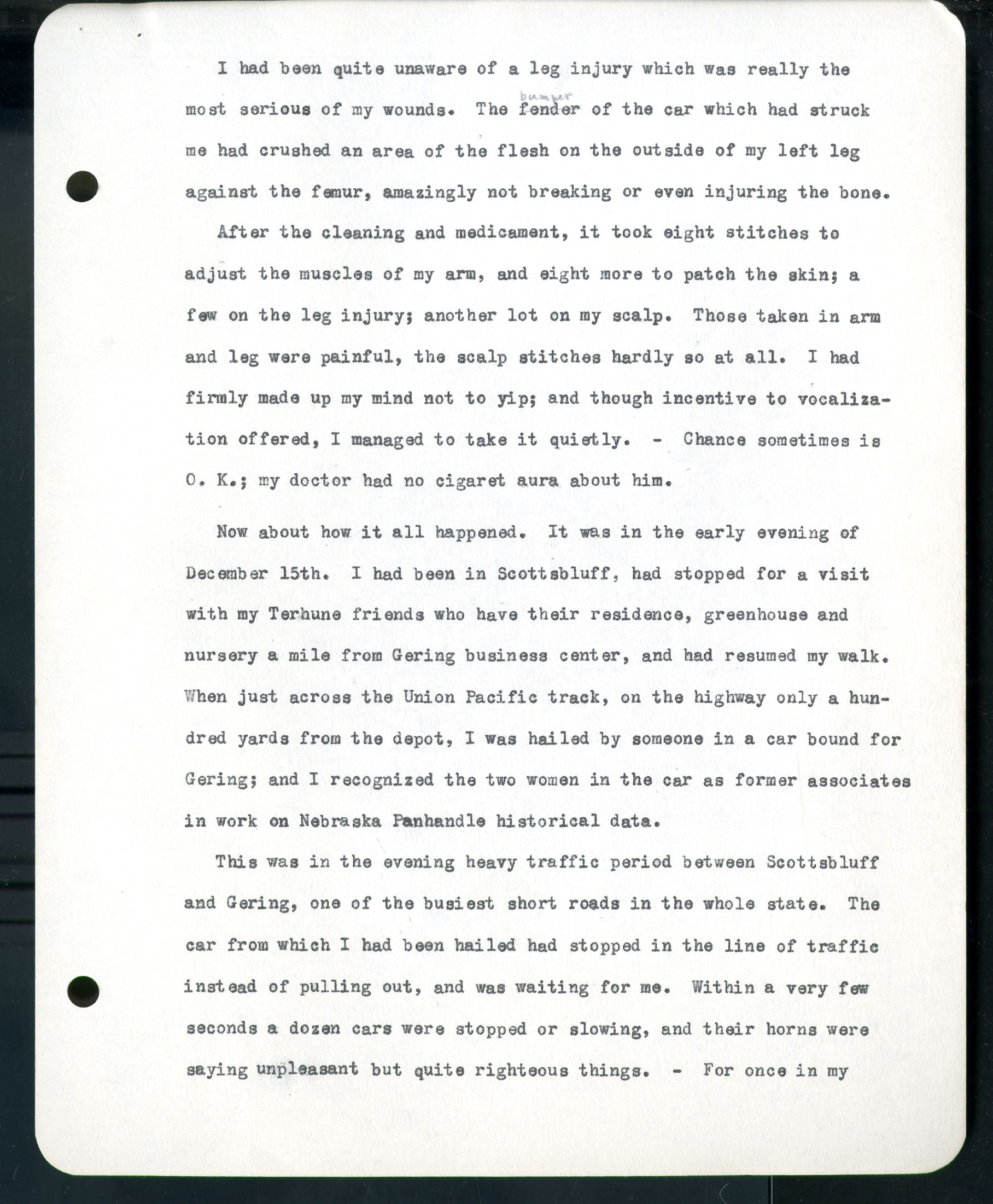

I had been unaware of a leg injury which was really the most serious of my wounds. The fender bumper of the car which had struck me and crushed an area of the flesh on the outside of my left leg against the femur, amazingly not breaking or even injuring the bone.

After the cleaning and medicament, it took eight stitches to adjust the muscles of my arm, and eight more to patch the skin; a few on the leg injury; another lot on my scalp. Those taken in arm and leg were painful, the scalp stitches hardly so at all. I had firmly made up my mind not to yip; and though incentive to vocalization offered, I managed to take it quietly. – Chance sometimes is O. K.; my doctor had no cigaret aura about him.

Now about how it all happened. It was in the early evening of December 15th. I had been in Scottsbluff, had stopped for a visit with my Terhune friends who have their residence, greenhouse and nursery a mile from Gering business center, and had resumed my walk. When just across the Union Pacific track, on the highway only a hundred yards from the depot, I was hailed by someone in a car bound for Gering; and I recognized the two women in the car as former associates in work on Nebraska Panhandle historical data.

This was in the evening heavy traffic period between Scottsbluff and Gering, one of the busiest short roads in the whole state. The car from which I had been hailed had stopped in the line of traffic instead of pulling out, and was waiting for me. Within a very few seconds a dozen cars were stopped or slowing, and their horns were saying unpleasant but quite righteous things. – For once in my

Life I did not take proper care; I rushed to relieve this ridiculous situation; and I was struck by a car going north, in the near lane. It is interesting to me that I have not the faintest recollection of the car or of its impact; that I have no memory of even the slightest sense of pain.

The bumper fender stuck the left side of my left leg, five inches above the knee, as I (going westward) was barely entering the northbound lane; had I been another two or three inches forward it would have broken my thigh bone and probably killed me. The impact must have been with the extreme tip of the bumper fender, and was light enough to rotate my body slightly, and my own impetus was sufficient to thrust me, still upright, against the side of the rapidly moving car; and there I got my arm injury. The horizontal rather acute-pointed car door handle penetrated all of my clothing, ripped the main muscles to the humerus, even parting the thin, bone-clinging triceps, l and set me rolling; which accounts probably for most of the scalp injuries, and for the dust and the weed skewers imbedded in the torn muscles.

I was wearing, Decemberwise, a heavy mackinaw, a medium weight suit, a shirt, and light underwear; through all of these layers the car door handle passed and ripped the muscles clear to the bone. The doctor told me later that the main nerve of the arm lay exposed for an inch or more on the humerus, untouched!

The driver of the Wyoming car which had struck me came back at once, I remember, and voluntarily gave someone his name, residence,

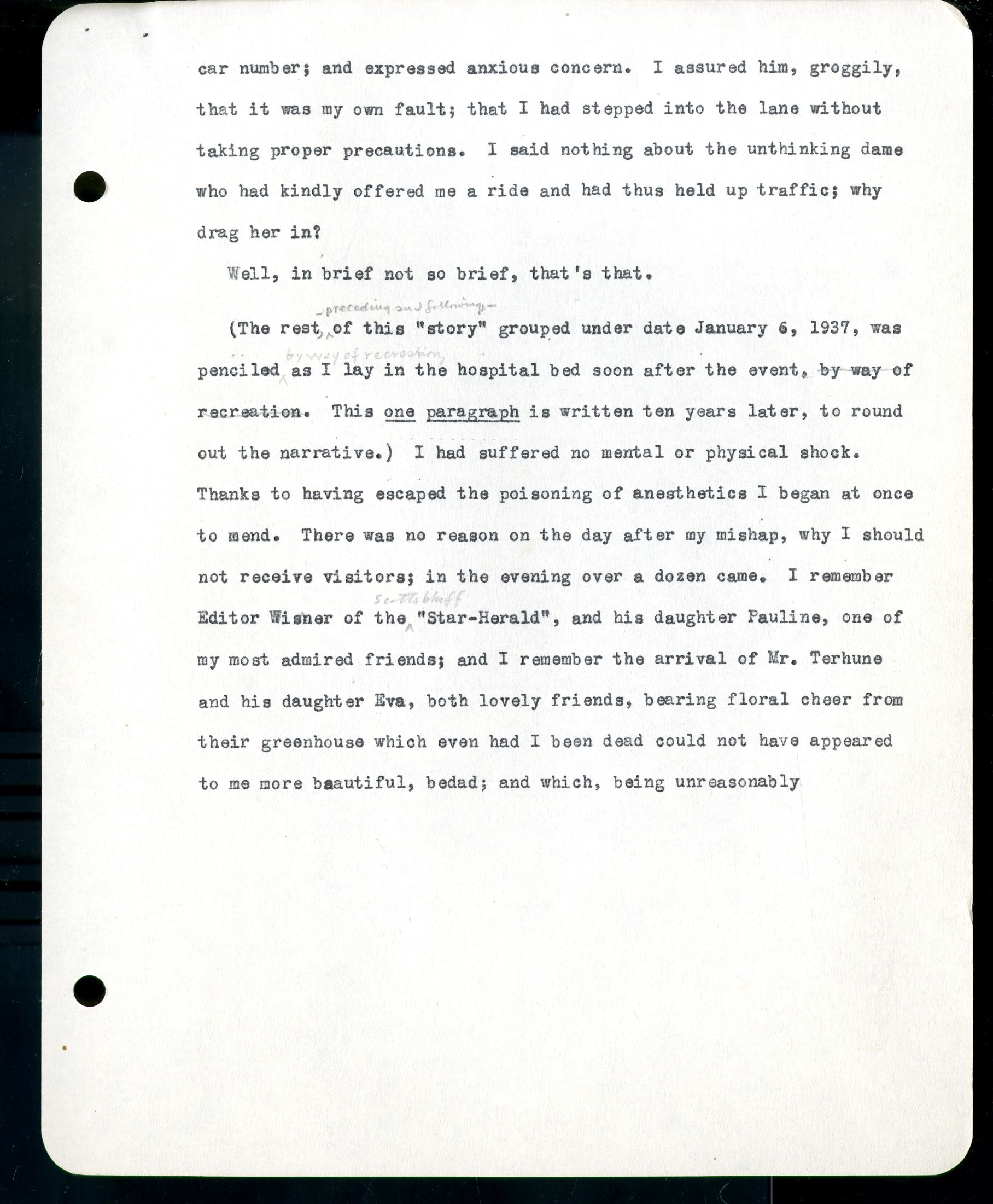

Car number; and expressed anxious concern. I assured him, groggily, that it was my own fault; that I had stepped into the lane without taking proper precautions. I said nothing about the unthinking dame who had kindly offered me a ride and had thus held up traffic; why drag her in?

Well, in brief not so brief, that’s that.

(That rest, preceding and following of this “story” grouped under date January 6, 1937, was penciled by way of recreation, as I lay in the hospital bed soon after the event, by way of recreation. This one paragraph is written ten years later, to round out the narrative.) I had suffered no mental or physical shock. Thanks to having escaped the poisoning of anesthetics I began at once to mend. There was no reason on the day after my mishap, why I should not receive visitors; in the evening over a dozen came. I remember Editor Wisner of the Scottsbluff “Star-Herald”, and his daughter Pauline, one of my most admired friends’ and I remember the arrival of Mr. Terhune and his daughter Eva, both lovely friends, bearing floral cheer from their greenhouse which even had I been dead could not have appeared to me more beautiful, bedad; and which , being unreasonably

January 6, 1937

1937 4

Jan 6 Scottsbluff, Nebraska

….It seems that someone was trying to get me to consider the absurd idea of entering a car, to be taken to a hospital. “Hospital?” I repeated dully; “no, thank you; I’m no hurt.”

Night was just setting in. Somehow, I had no sense of my placement; I was on the edge of a highway somewhere, and a street light was blazing almost overhead. My head did not ache, but there was an unaccustomed ringing inside it. For some reason not clear, a man had his arm affectionately about my waist, and two or three others were standing by. – My soft hat did not seem to fit properly, so I reached up to place it comfortably; and with my hands thus raised I chanced to get a look at my upper left arm.

A raw red mass it was, pulsing blood, with dripping rags suspended form it, jagged and backed as though cut with very dull shears; the torn cloth was nicely dusted over, and pieces of dead weeds were sticking out of the flesh like skewers. Viewing this evidence, it seemed pedantic to longer insist that I had not been hurt; the sensing of the fact that I somehow had been injured, however, brought to me no shock. I clearly remember that my viewing of the bad wound was quite impersonal, and that my interest was devoted entirely to the surgical procedure indicated. – Strangely, I remember precisely what I said:

“Well, I guess I am hurt a little.”

As I was bleeding profusely from several scalp wounds, the blood oozing out under my hat-band and selecting tangents across my cheeks, all unknown to me, this admission must have afforded my listeners an impressive example of under-statement.

I was conducted to a car and we rushed to Gering, only a half mile distant: the driver, myself, and a good Samaritan whose name I never learned. Immediately after seeing the flow of blood from the arm wound I had stuck my right hand inside my clothing next to the skin and had used them and fingers as a tourniquet; I remember how they ached from the long-continued pressure.

I was asked which of the two Gering doctors I wished to handle the matter. I knew neither personally, but I remembered that one of them I had seldom seen on the street without a cigaret in his face or fingers; so on a chance I indicated the other. Contact with this doctor fortunately was prompt, and I began to receive proper attention. The doctor explained, as he did the first things, that the cleaning and stitching would be painful, and that he would give me an anesthetic.

Twenty-eight years before, I had had my sole hospital experience; a burst appendix, peritonitis. I remembered the stultifying and retarding effect upon recovery, of my anesthetic (absolutely necessary in that case); so I told the doctor that, unless he definitely ordered anesthesia, as was his right, I would prefer to consciously stand the pain. He was kind enough to let me have it my way; reassuring me, however, that it would hurt plenty. – As a diagnostician he approached perfection; it did hurt plenty.

I had been unaware of a leg injury which was really the most serious of my wounds. The fender bumper of the car which had struck me and crushed an area of the flesh on the outside of my left leg against the femur, amazingly not breaking or even injuring the bone.

After the cleaning and medicament, it took eight stitches to adjust the muscles of my arm, and eight more to patch the skin; a few on the leg injury; another lot on my scalp. Those taken in arm and leg were painful, the scalp stitches hardly so at all. I had firmly made up my mind not to yip; and though incentive to vocalization offered, I managed to take it quietly. – Chance sometimes is O. K.; my doctor had no cigaret aura about him.

Now about how it all happened. It was in the early evening of December 15th. I had been in Scottsbluff, had stopped for a visit with my Terhune friends who have their residence, greenhouse and nursery a mile from Gering business center, and had resumed my walk. When just across the Union Pacific track, on the highway only a hundred yards from the depot, I was hailed by someone in a car bound for Gering; and I recognized the two women in the car as former associates in work on Nebraska Panhandle historical data.

This was in the evening heavy traffic period between Scottsbluff and Gering, one of the busiest short roads in the whole state. The car from which I had been hailed had stopped in the line of traffic instead of pulling out, and was waiting for me. Within a very few seconds a dozen cars were stopped or slowing, and their horns were saying unpleasant but quite righteous things. – For once in my

Life I did not take proper care; I rushed to relieve this ridiculous situation; and I was struck by a car going north, in the near lane. It is interesting to me that I have not the faintest recollection of the car or of its impact; that I have no memory of even the slightest sense of pain.

The bumper fender stuck the left side of my left leg, five inches above the knee, as I (going westward) was barely entering the northbound lane; had I been another two or three inches forward it would have broken my thigh bone and probably killed me. The impact must have been with the extreme tip of the bumper fender, and was light enough to rotate my body slightly, and my own impetus was sufficient to thrust me, still upright, against the side of the rapidly moving car; and there I got my arm injury. The horizontal rather acute-pointed car door handle penetrated all of my clothing, ripped the main muscles to the humerus, even parting the thin, bone-clinging triceps, l and set me rolling; which accounts probably for most of the scalp injuries, and for the dust and the weed skewers imbedded in the torn muscles.

I was wearing, Decemberwise, a heavy mackinaw, a medium weight suit, a shirt, and light underwear; through all of these layers the car door handle passed and ripped the muscles clear to the bone. The doctor told me later that the main nerve of the arm lay exposed for an inch or more on the humerus, untouched!

The driver of the Wyoming car which had struck me came back at once, I remember, and voluntarily gave someone his name, residence,

Car number; and expressed anxious concern. I assured him, groggily, that it was my own fault; that I had stepped into the lane without taking proper precautions. I said nothing about the unthinking dame who had kindly offered me a ride and had thus held up traffic; why drag her in?

Well, in brief not so brief, that’s that.

(That rest, preceding and following of this “story” grouped under date January 6, 1937, was penciled by way of recreation, as I lay in the hospital bed soon after the event, by way of recreation. This one paragraph is written ten years later, to round out the narrative.) I had suffered no mental or physical shock. Thanks to having escaped the poisoning of anesthetics I began at once to mend. There was no reason on the day after my mishap, why I should not receive visitors; in the evening over a dozen came. I remember Editor Wisner of the Scottsbluff “Star-Herald”, and his daughter Pauline, one of my most admired friends’ and I remember the arrival of Mr. Terhune and his daughter Eva, both lovely friends, bearing floral cheer from their greenhouse which even had I been dead could not have appeared to me more beautiful, bedad; and which , being unreasonably

June 1937 Excerpts

Excerpts.

Excerpts.

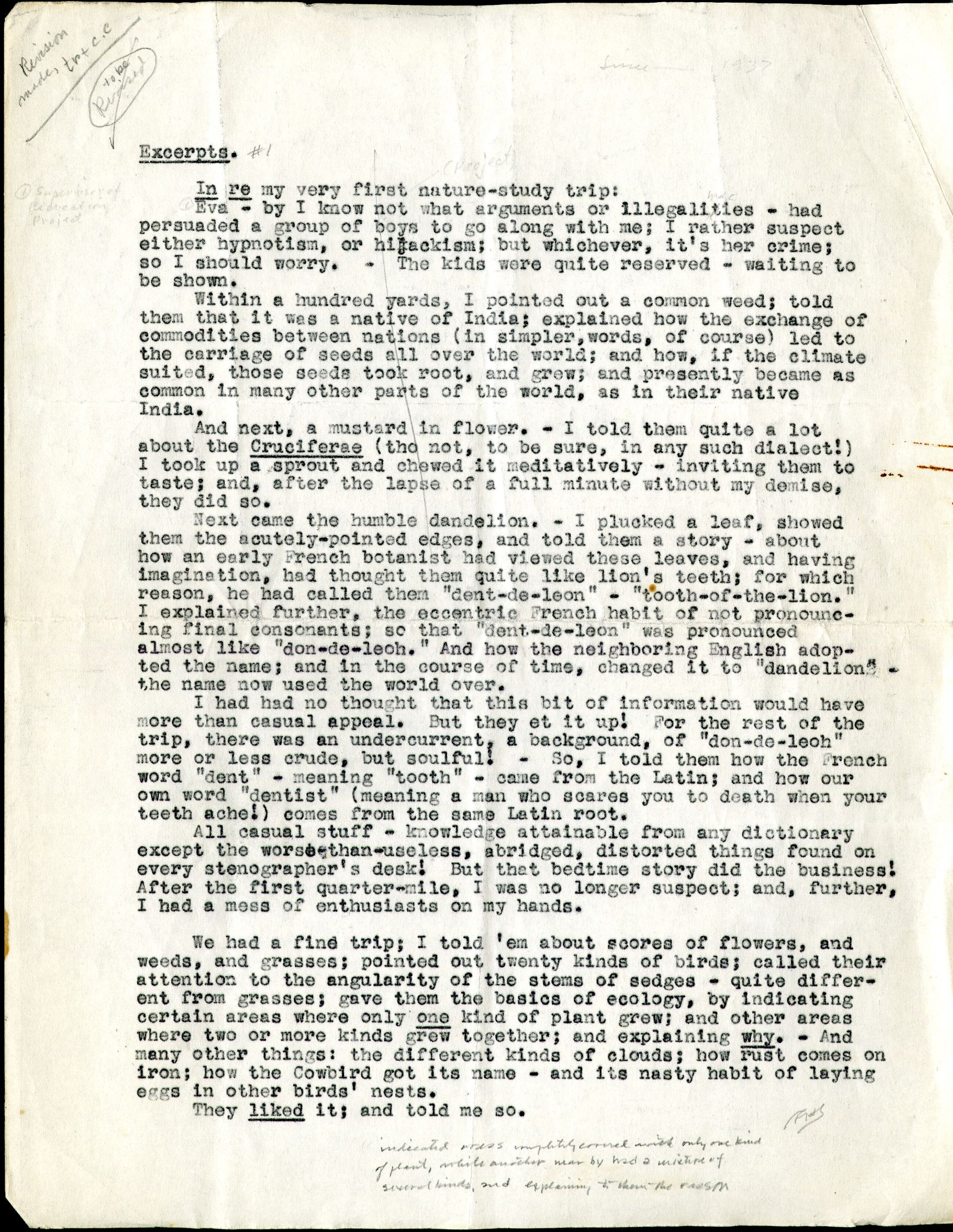

In re my very first nature-study trip:

Eva – by I know not what arguments or illegalities – had persuaded a group of boys to go along with me; I rather suspect either hypnotism, or hijackism; but whichever, it’s her crime; so I should worry. – The kids were quite reserved – waiting to be shown.

Within a hundred yards, I pointed out a common weed; told them that it was a native of India; explained how the exchange of commodities between nations (in simpler words, of course) led to the carriage of seeds all over the world; and how, if the climate suited, those seeds took root, and grew; and presently became as common in many other parts of the world, as in their native India.

And next, a mustard in flower. – I told them quite a lot about the Cruciferae (tho not, to be sure, in any such dialect!) I took up a sprout and chewed it meditatively – inviting them to taste; and, after the lapse of a full minute without my demise, they did so.

Next came the humble dandelion. – I plucked a leaf, showed them the acutely-pointed edges, and told them a story, about how an early French botanist had viewed these leaves, and having imagination, had thought them quite like lion’s teeth; for which reason, he had called them “dent-de-lion” – “tooth-of-the-lion.” I explained further, the eccentric French habit of not pronouncing final consonants; so that “dent-de-lion” was pronounced almost like “don-de-leoh.” And how the neighboring English adopted the name; and in the course of time, changed it to “dandelion,” the name now used the world over.

I had no thought that this bit of information would have more than casual appeal. But they et it up! For the rest of the trip, there was an undercurrent, a background, of “don-de-leoh” more or less crude, but soulful! – So I told them how the French word “dent” – meaning “tooth” – came from the Latin; and how our own word “dentist” (meaning a man who scares you to death when your teeth ache!) comes from the same Latin root.

All casual stuff – knowledge attainable from any dictionary except the worse-than-useless, abridged, distorted things found on every stenographer’s desk! But that bedtime story did the business! After the first quarter-mile, I was no longer suspect; and, further, I had a mess of enthusiasts on my hands.

We had a fine trip; I told ‘em about scores of flowers, and weeds, and grasses; pointed out twenty kinds of birds; called their attention to the angularity of the stems of sedges – quite different from grasses; gave them the basics of ecology, by indicating certain areas where only one kind of plant grew; and other areas where two or more kinds grew together; and explaining why. – And many other things: the different kinds of clouds; how rust comes on iron; how the Cowbird got its name – and its nasty habit of laying eggs in other birds’ nests.

They liked it; they told me so.

1937

1937

Scottsbluff, Nebraska June 5

Today occurred my first nature-study trip from Overland Park with three boys, 9 to 12 years old. They were quite without enthusiasm, naturally, for to them it was an unknown venture; and as always with a new party, I myself had to feel my way for a time.

Within a hundred yards, by the roadside, I found one of our common weeds in flower. I plucked and shoed them one of the young leaves while telling a little of its history; in effect:

that it was a kind of plant which is native to Europe;

that quite early in the settlement of American by European people, some of its seeds were brought across the ocean – perhaps mixed with grain like wheat or oats intended for planting crops;

that the soil and climate favored the growth of this plant, which now after two or three hundred years has spread until it is found in many states.

So formally tabulated, these items are rather distressing; but imparting the facts conversationally took up only a minute or two. Then I put the leaf in my mouth and chewed it meditatively; gathering and passing around more of the tender leaves I invited them to do likewise. They were hesitant about doing so, but after a full minute had passed without my demise they made the experiment. – In a moment of the boys said, “Why, it tastes like mustard.”

“Exactly,” I stated, “that’s just what it is. Some of the mustards are grown for food uses, affording the prepared mustard which you like on your hamburgers or weenies.” (“Wiener,” please be advised, is a stuck-up word, not favored by the right kind of boys.)

Next we examined a dandelion, which of course all of the boys knew by name. I asked if they knew why it was called a dandelion; and naturally, they did not. So I plucked a leaf, showed them the peculiar, jagged edges, each part with a sharp point; then I told them a story – about how an early French botanist had viewed these leaves and was struck with the notion that each of the sharp-pointed jags was shaped like a lion’s tooth as viewed from the side. So he named the plant dent-de-leon – which is French for “tooth of the lion.”

Next we examined a dandelion, which of course all of the boys knew by name. I asked if they knew why it was called a dandelion; and naturally, they did not. So I plucked a leaf, showed them the peculiar, jagged edges, each part with a sharp point; then I told them a story – about how an early French botanist had viewed these leaves and was struck with the notion that each of the sharp-pointed jags was shaped like a lion’s tooth as viewed from the side. So he named the plant dent-de-leon – which is French for “tooth of the lion.”

I explained as best I might, the eccentric French habit of not always pronouncing final consonants; so that “dent-de-leon” was pronounced almost as though it were spelled don-de-leoh with the accent on the last syllable (it looks awful as typed but I gave them a fair drilling in the way it should sound). – And I explained how the neighboring English across the Channel adopted the name modifying it in the course of the trip often there was soulful practice of that wonderful word.

The stories of a mustard and of the dandelion have been so fully outlined only for the purpose of indicating the direction and character of our “study” of such common things as offered during this short trip. I named a score of flowers for them, as many weeds, several grasses; called their attention to the angularity of the stems of sedges – quite different from grasses; indicated a small area completely covered with

only one kind of plant, while a like space near by had a mixture of several kinds, and explaining to them the reason. We saw and I named for them over twenty kinds of birds, of which of course they already knew several. The different kinds of clouds; how rust comes on iron; – we never ran out of subjects!

only one kind of plant, while a like space near by had a mixture of several kinds, and explaining to them the reason. We saw and I named for them over twenty kinds of birds, of which of course they already knew several. The different kinds of clouds; how rust comes on iron; – we never ran out of subjects!

“Gee! this has been fine! When can we take another trip?”

1937

1937

Had a walk this afternoon (1:30-6:30) with five boys. Overland Park, cross the bridge, to CCC camp 762 northwest of the Bluff; and return. Eight or ten miles.

BIRD LIST

great blue heron black-crowned night heron American bittern gull – sp.? common tern kingfisher northern yellowthroat yellow warbler goldfinch red-winged blackbird cowbird magpie Arkansas flycatcher kingbird cliff swallow bank swallow sparrow hawk downy woodpecker brown thrasher violet-green swallow western warbling vireo

A pleasant afternoon; at first with too much breeze and with white clouds flying eastward; but quiet later, with a soft half-light disclosing delicate tones of color not to be discerned on a bright day. Temperature very mild. The whole region is glorying in the recent rains; flowers of many species are encouraged to open. The distantly-visible talus slopes of the Bluff and the short-grass plains, which display through most of the year a discouraged gray-brown tone, are now clad in green. The normally buff-colored slopes and walls of Brule and Gering formation still show a reddish tone, due to retained moisture.

False Solomon’s seal is past blooming. . . Roses of two species in full flower and very beautiful. . . False indigo very plentiful; it will flower next week. . . The pretty white pentstemon still in bloom, but past its prime.

Surprised to find, on north slopes which get no sunlight, two early species still in flower: Townsendia exscapa, and Zygadenus.

Wild currants have half-size berries; having first coaxed the boys to taste, I had then to bid them desist, to avoid later stomach-aches. Compromising, they grazed for most of the afternoon on rose-petals.

Late in the afternoon we found dead, a very beautiful bird: the violet-green swallow. I tried tonight to make of it a presentable skin, but its state would not permit. However, I made measurements and preserved color notes, which are given here:

Late in the afternoon we found dead, a very beautiful bird: the violet-green swallow. I tried tonight to make of it a presentable skin, but its state would not permit. However, I made measurements and preserved color notes, which are given here:

Violet-green Swallow. – A dead specimen, found west of Gering, Nebr., June 7. 1937, near U. F. tracks. A blood clot on the right frontal area of the skull indicates rather conclusively that the bird died by reason of striking a telegraph wire.

Measurements: Length: bill to tip of tail, 5.5 inches bill to tip of wings, 6 inches Extent: 11.75 inches Wing: 4.5 inches Tail: 1.75 inches Bill: tip to fronts, 3/16 inch along gape, 7/16 inch

Color notes: Bill: black Feet: brownish Lores, throat, breast, belly: white; almost confluent white across base of rump. Back, and washing shoulders, and onto upper wings: bright green Rump: violet-purple Head: black; obscurely brownish toward nape Two middle tail-feathers (shortest): white

My first sight of this species was on June 12, 1904, in Macleay Park at Portland, Oregon. Since then I have encountered it often, not only at many places in the Rocky Mountains, but in all of the Nebraska counties bordering the Wyoming state line. But today is the first time I have ever had a specimen in my hand.

We found a nest of the magpie, a half-wagonload of twigs in a clump of willows; four young birds were perched upon the branches about it. We caught three of the four, and dearly hoped for a photograph. But they were three days too old, and would not stay put. They fought

valiantly, yelling at the top of their voices; while the parent birds sat near by, or swooped threateningly, shouting instructions. We left the babies in their tree.

valiantly, yelling at the top of their voices; while the parent birds sat near by, or swooped threateningly, shouting instructions. We left the babies in their tree.

Some of the boys urged, almost with tears, that they be permitted to take the birds for pets. But, knowing how this works out in about 95% of the efforts, I was constrained to forbid. Not insistingly, but argumentatively; pointing out how unnatural it is for a wild bird to be confined for the passing pleasure of its master; how much better to allow it freedom to fly scores of miles every day, than to stick it into a little cage in the back yard. – It pleases me to record that the boys were splendidly amenable to reason; while they terribly wanted those birds, they sensed the weight of argument to the contrary.

The boys reveled in a badger-hole, washed through from above, affording a wondrous cavern which the youngsters must needs traverse time and again, with assorted whoops; getting handfuls of clay down their shirt collars.

In the badlands we found a mere trickle of water; perhaps a pint perminute. This was off the Scott’s Bluff National Monument grounds; so I felt free to establish, with the boys, a little Submarginal-lands Reclamation Project of our own. The trickle was almost lost in the Lower Brule much; so with our paws we scooped out several cubic feet of the slippery stuff; cleared a run-off channel, being careful to maintain a suitable rim for the basin; and went on our way rejoicing. The water is very good to drink, and surprisingly cold; and its location is a