Great Nebraska

Naturalists and Scientists When assembled, my notes relating to the Lincoln Salt Basin will total over a hundred typed pages, accompanied by over a hundred photographs.

When assembled, my notes relating to the Lincoln Salt Basin will total over a hundred typed pages, accompanied by over a hundred photographs.

This small section of that unassembled total, is sent by reason of the preliminary description (June 29 1902) of that remarkable bird habitat – see accomp. lists May 22, 1904; May 6-7, 1911

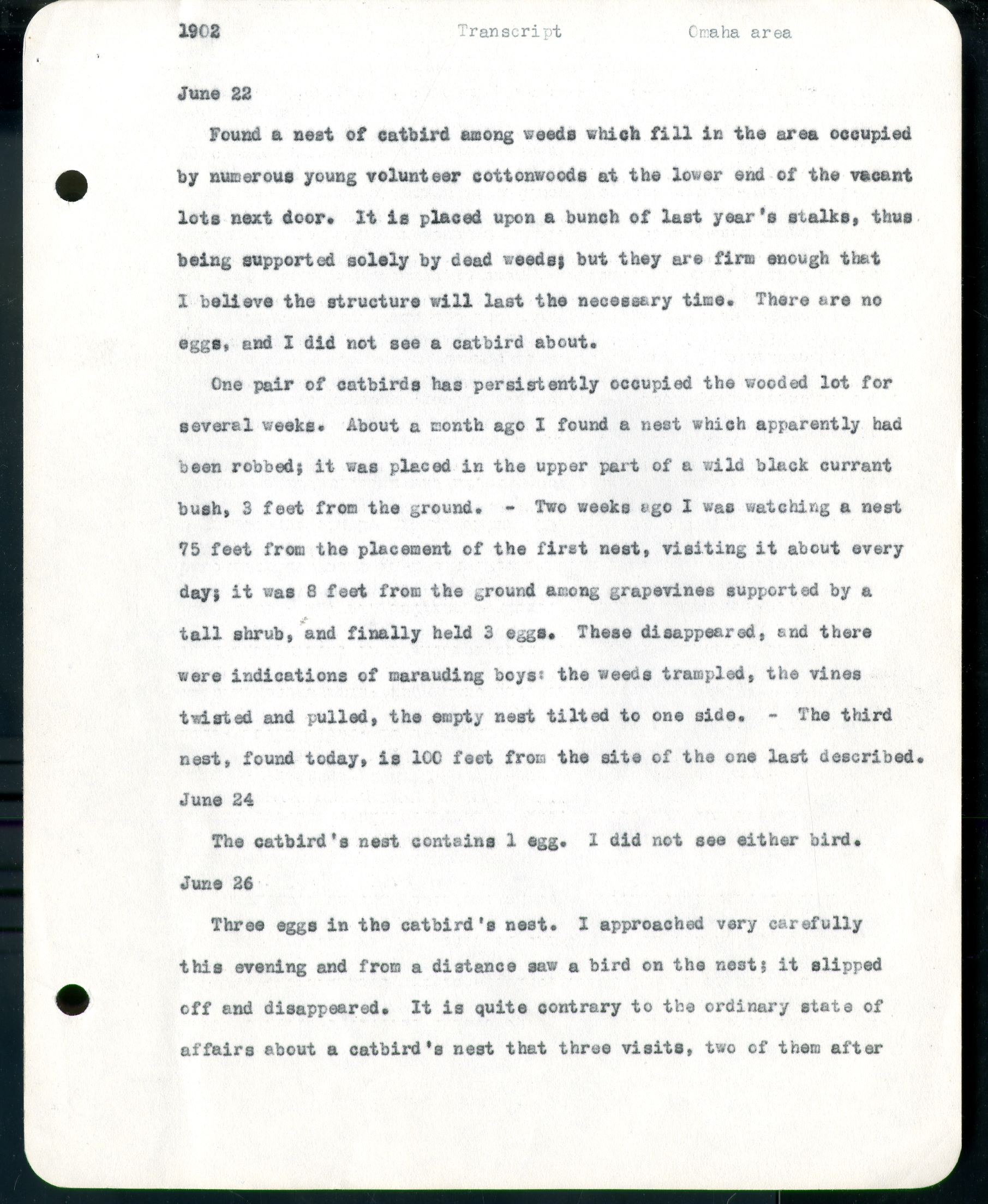

1902 Transcript Omaha area

1902 Transcript Omaha area

June 22

Found a nest of catbird among weeds which fill in the area occupied by numerous young volunteer cottonwoods at the lower end of the vacant lots next door. It is placed upon a bunch of last year’s stalks, thus being supported solely by dead weeds; but they are firm enough that I believe the structure will last the necessary time. There are no eggs, and I did not see a catbird about.

One pair of catbirds has persistently occupied the wooded lot for several weeks. About a month ago I found the nest which apparently had been robbed; it was placed in the upper part of a wild black currant bush, 3 feet from the ground. – Two weeks ago I was watching a nest 75 feet from the placement of the first nest, visiting it about every day; it was 8 feet from the ground among grapevines supported by a tall shrub, and finally held 3 eggs. These disappeared, and there were indications of marauding boys: the weeds trampled, the vined twisted and pulled, the empty nest tilted to one side. – The third nest, found today, is 100 feet from the site of the last one described.

June 24

The catbird’s nest contains 1 egg. I did not see either bird.

June 26

Three eggs in the catbird’s nest. I approached very carefully this evening and from a distance saw a bird on the nest; it slipped off and disappeared. It is quite contrary to the ordinary state of affairs about a catbird’s nest that three visits, two of them after

eggs had been laid, should have elicited not one note of protest from the birds, and that they remained invisible; generally they are actively and noisily present. By habit I always approach by different wats any nest under frequent observation, carefully avoiding any displacement of or damage to plants; for nothing is more certain to effect the destruction of a nest than to make a path to it.

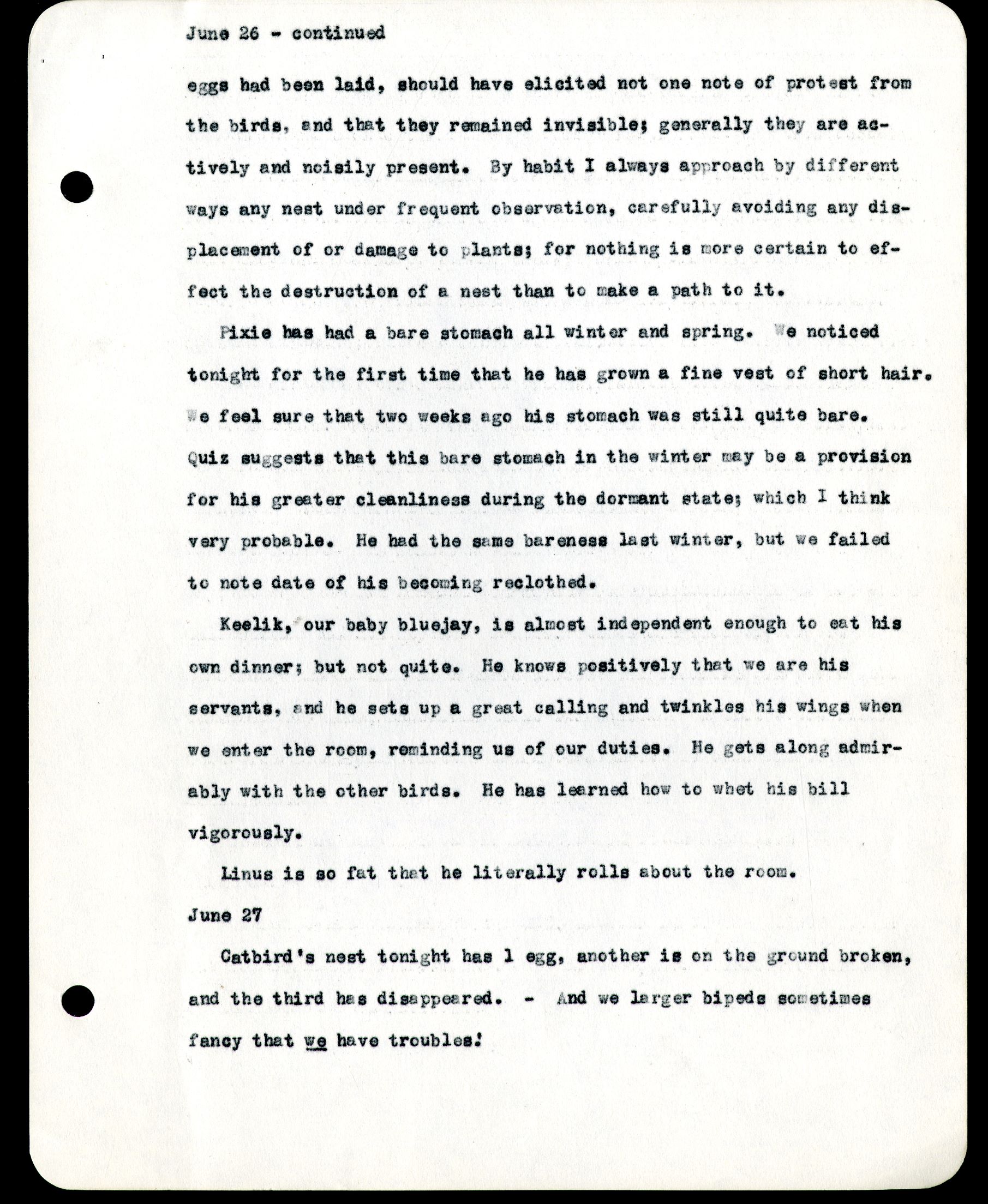

eggs had been laid, should have elicited not one note of protest from the birds, and that they remained invisible; generally they are actively and noisily present. By habit I always approach by different wats any nest under frequent observation, carefully avoiding any displacement of or damage to plants; for nothing is more certain to effect the destruction of a nest than to make a path to it.

Pixie has had a bare stomach all winter and spring. We noticed tonight for the first time that he has grown a fine vest of short hair. We feel sure that two weeks ago his stomach was still quite bare. Quiz suggests that this bare stomach during the winter may be a provision for his greater cleanliness during the dormant state; which I think very probable. He had the same bareness last winter, but we failed to note the date of his becoming reclothed.

Keelik, our baby bluejay, is almost independent enough to eat his own dinner; but not quite. He knows positively that we are his servants, and he sets up a great calling and twinkles his wings when we enter the room, reminding us of our duties. He gets along admirably with the other birds. He has learned how to whet his bill vigorously.

Linus is so fat that he literally rolls about the room.

June 27

Catbird’s nest tonight has 1 egg, another is on the ground broken, and the third has disappeared. – And we larger bipeds sometimes fancy that we have troubles!

June 29 — Lincoln, Nebraska

June 29 — Lincoln, Nebraska

Came down last night to go with Dr. Wolcott on an expedition to the Salt Basin, northwest of town. It rained steadily all day until about 4 p m, when we left the house.

The Salt Basin is a natural minor depression draining many square miles. Its salinity arises chiefly from a large gushing spring near its southwestern border which affords a considerable volume of salt water; but there are many lesser springs. As the actual water surface, which covers perhaps two square miles, varies in area periodically by reason of run-in water from the melting of snow in the drainage area, and intermittently when heavy rains come, there are no naturally established banks as boundaries, though there is some rock work put in to retain water in the “lake bed,” done long ago to afford a summer playground; for Lincoln, established on rolling grassland, has about it nothing scenically attractive. Some years ago this playground of sorts was knowns of Burlington Beach as a resort; the rock work was not kept in repair; the water now covers its natural instead of an artificially maintained level, at no point deeper than 12 to 18 inches except briefly after melting of snow or by reason of heavy rainfall.

The “lake” area being approximately two square miles, there is an additional and perhaps equal bordering area where the water is very

June 29 – continued

June 29 – continued

shallow; and these shallows have afforded, for centuries, a feeding ground for shore-birds – snipe, plover, and their like. Innumerable dipterous insects breed here; and their larvae, by the trillions, have made the Salt Basin a favored stop-over point for migrants, and a residence for many species. – I am tempted to carry on here and tell more about this area and its birds, but the subject is too vast; even my assembled, and those admittedly preliminary, notes, will fill 20 pages like this. I feel in duty bound to cover the topic to the best of my ability, but as an amateur in both ornithology and ecology I am scared stiff; surely the pants of savantship will bag on me when I step in! However & anyhow, my Salt Basin story shall be recorded later.

The mud flats about the Salt Basin, wide and level, after a bit of drying show quantities of crystallized salt. These flats afford habitat in their varying zones for many species of beetles, among which the leading interest of Dr. Wolcott and myself centers in Cicindelidae, or tiger beetles. However, on this trip, the soaked earth kept every tiger beetle out of sight; for they are sun-lovers.

About 30 years ago (1871 or 1872), records tell us that there was at one time approximately two thousand Indians camped here to get their year’s supply of salt from the big spring.

The borders of this wet spot – of course within the drainage area but sufficiently elevated to be free from excessive moisture and from destructive salinity – are occupied almost wholly by land under cultivation. A trip around the lake is always interesting to an observer

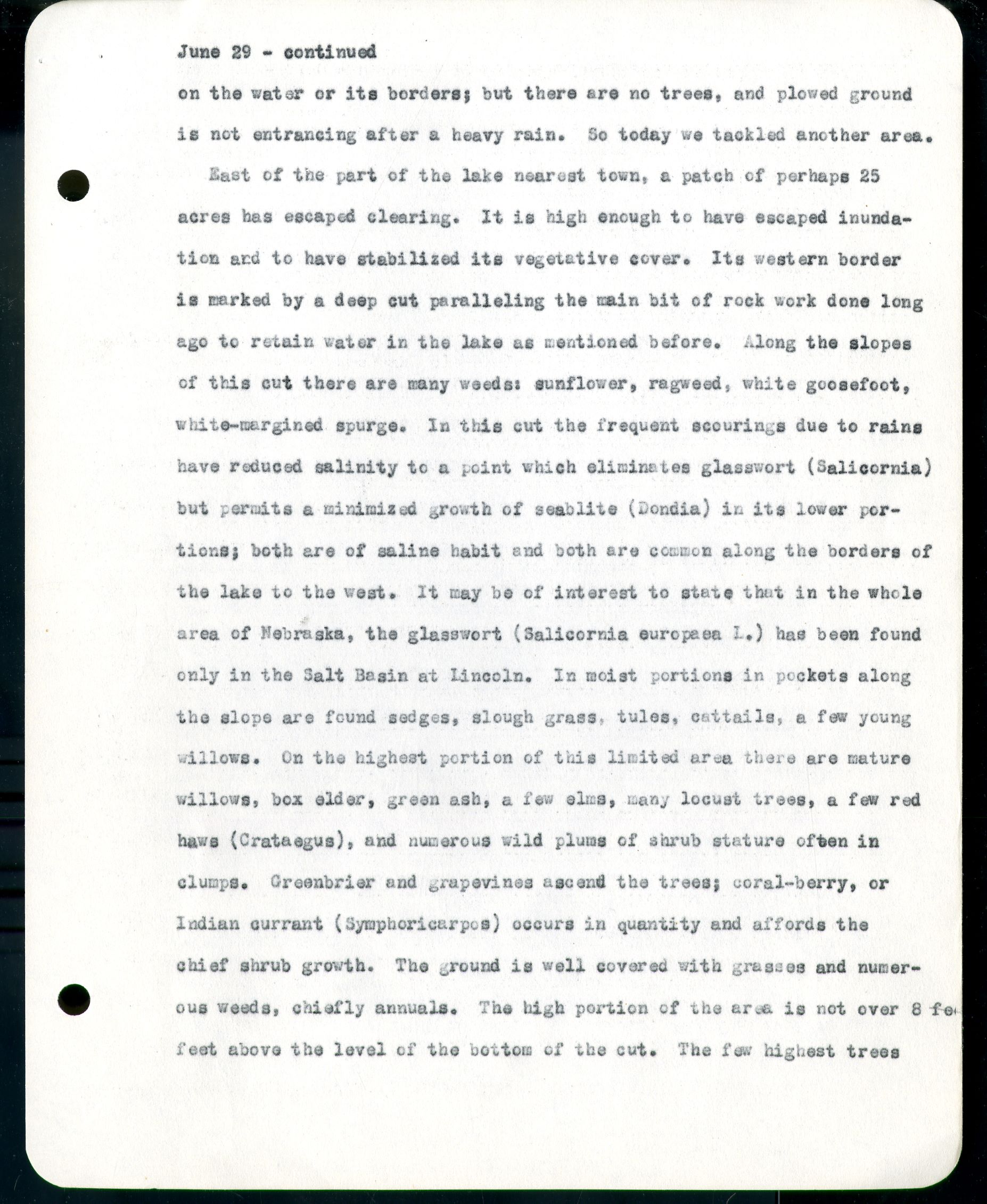

June 29 – continued

June 29 – continued

on the water of its borders; but there are no trees, and plowed ground is not entrancing after a heavy rain. So today we tackled another area.

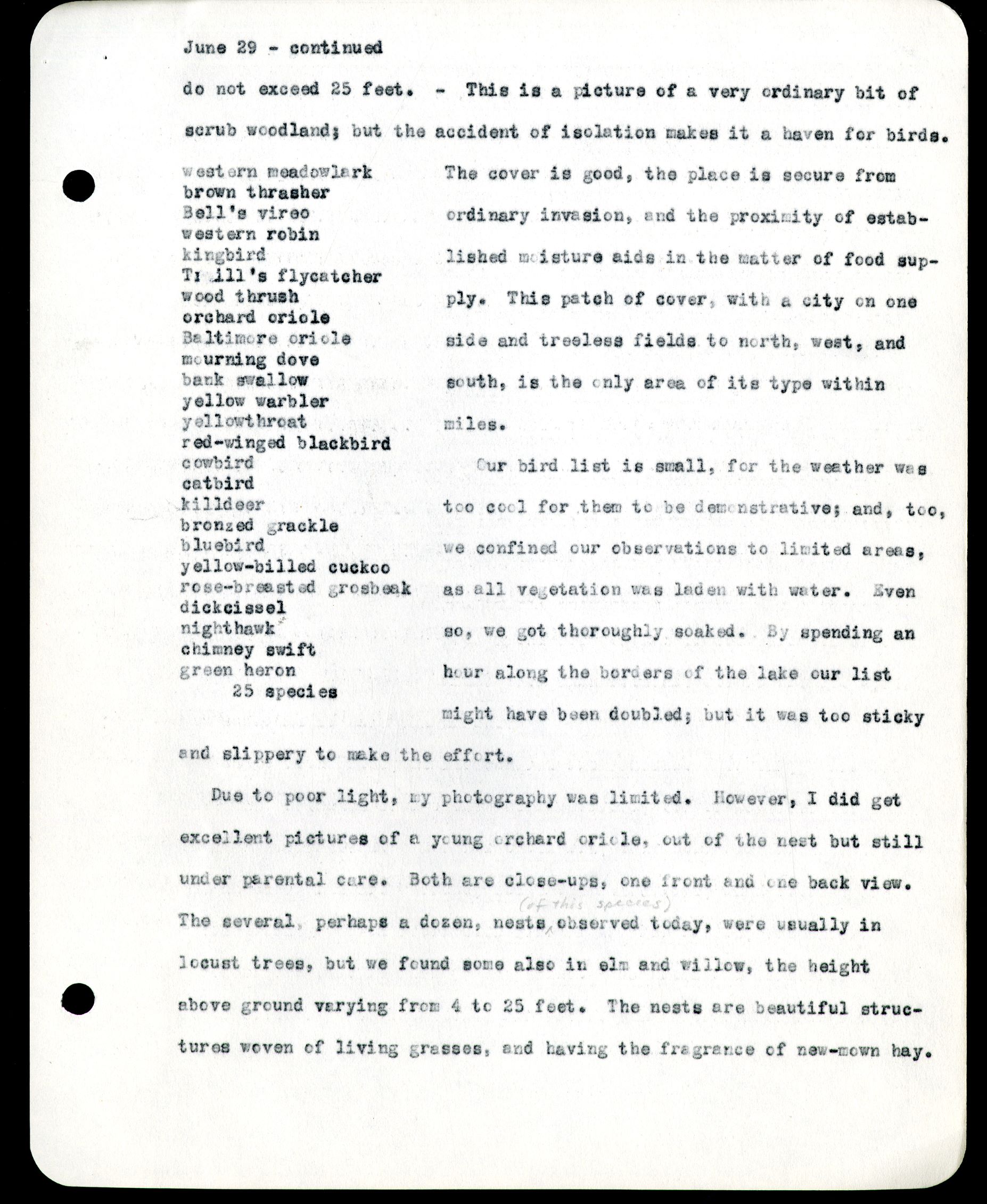

East of the part of the lake nearest town, a patch of perhaps 25 acres has escaped clearing. It is high enough to have escaped inundation and to have stabilized its vegetative cover. Its western border is marked by a deep cut paralleling the main bit of rock work done long ago to retain water in the lake as mentioned before. Along the slopes of this out there are many weeds: sunflower, ragweed, white goosefoot, white-margined spurge. In this cut the frequent scourings due to rains have reduced salinity to a point which eliminates glasswort (Salicornia) but permits a minimized growth of seablite (Dondia) in its lower portions; both are of saline habit and both are common along the borders of the lake to the west. It may be of interest to stare that in the whole area of Nebraska, the glasswort (Salicornia europaea L.) has been found only in the Salt Basin at Lincoln. In moist portions in pockets along the slope are found sedges, slough grass, tules, cattails, a few young willows. On the highest portion of this limited area there are mature willows, box elder, green ash, a few elms, many locust trees, a few red haws (Crataegus), and numerous wild plums of shrub stature often in clumps. Greenbrier and grapevines ascend the trees; coral-berry, or Indian currant (Symphoricarpos) occurs in quantity and afford the chief shrub growth. The ground is well covered with grasses and numerous weeds, chiefly annuals. The high portion of the area is mot over 8 feet above the level of the bottom of the cut. The few highest trees

do not exceed 25 feet. – This is a picture of a very ordinary bit of Shrub woodlands; but the accident of isolation makes it a haven for birds.

western meadowlark

brown thrasher

Bell’s vireo

western robin

kingbird

Traill’s flycatcher

wood thrush

orchard oriole

Baltimore oriole

mourning dove

bank swallow

yellow warbler

yellowthroat

red-winged blackbird

cowbird

catbird

killdeer

bronzed grackle

bluebird

yellow-billed cuckoo

rose-breasted grosbeak

dickcissel

nighthawk

chimney swift

green heron

25 species

The cover is good, the place is secure from ordinary invasion, and the proximity of established moisture aids in the matter of food supply. This patch of cover, with a city on one side and treeless fields to north, west, and south, is the only area of its type within miles.

Our bird list is small, for the weather was too cool for them to be demonstrative; and, too, we confined our observations to limited areas, as all vegetation was laden with water. Even so, we got thoroughly soaked. By spending an hour among the borders of the lake our list might have been doubled; but it was too sticky and slippery to make the effort.

Due to poor light, my photography was limited. However, I did get excellent pictures of a young orchard circle, out of the nest but still under parental care. Both are close-ups, one front and one back view. The several, perhaps a dozen, nests of this species observed today, were usually in locust trees, but we found some also in elm and willow, the height above ground varying from 4 to 25 feet. The nests are beautiful structures woven of living grasses, and having the fragrance of new-mown hay.

A nest of Traill’s flycatcher found, contained one lubberly young cowbird; no sign of eggs or young flycatchers. I rebelled as usual, but could not bring myself to the point of performing the reasonable and defensible execution. Why Mother Nature should have wished the scourge of cowbirds upon innocent and friendly birds is beyond comprehension.

We found the following nests:

yellow warbler 4 eggs

orchard oriole 12 eggs or young

Baltimore oriole 1 not examined

catbird 3 1 with young, 2 with eggs

dickcissel 1 eggs

brown thrasher 1 3 young

mourning dove 3 eggs or young

kingbird 3 2 not examined; 1 with 3 young, dead

Traill’s flycatcher 2 1 with eggs; 1 with 1 young cowbird

robin 2 not examined; prob. post-nid.

yellow-billed cuckoo 1 building

red-winged blackbird – colony, perhaps 20; not examined

We found a nest with 4 young orchard orioles, dead; a nest of the kingbird with 3 young, dead; a nest of the mourning dove with one young bird dead and one pipped live egg. At first inclined to believe that destruction of the parent birds might have been the explanation, we concluded that prolonged cold weather was to blame.

June 30 Omaha

Took several photographs of our young bluejay. His vocal performances are becoming mature, and he is by way of being a big bird. As yet he is perfectly at peace with the other birds.

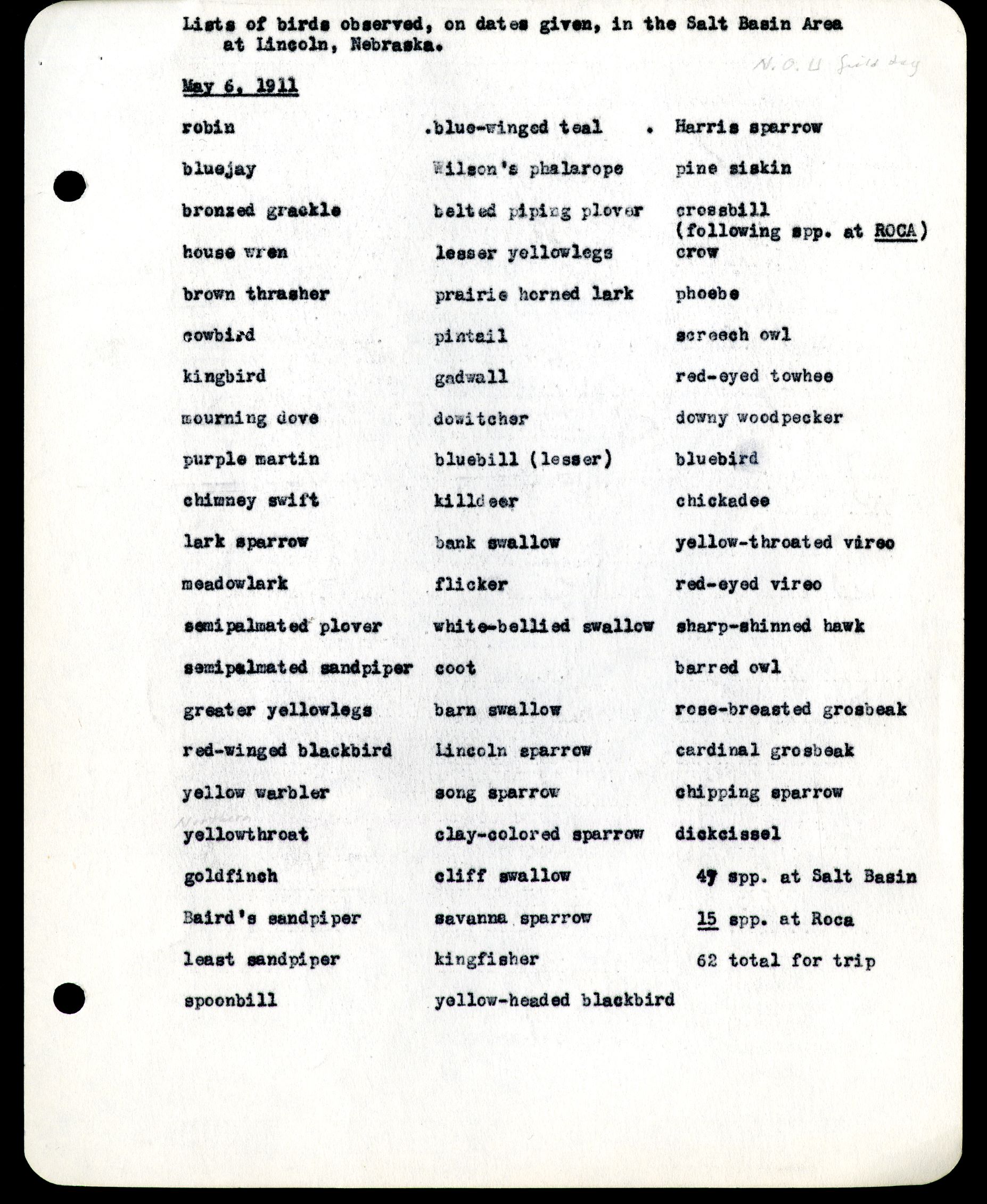

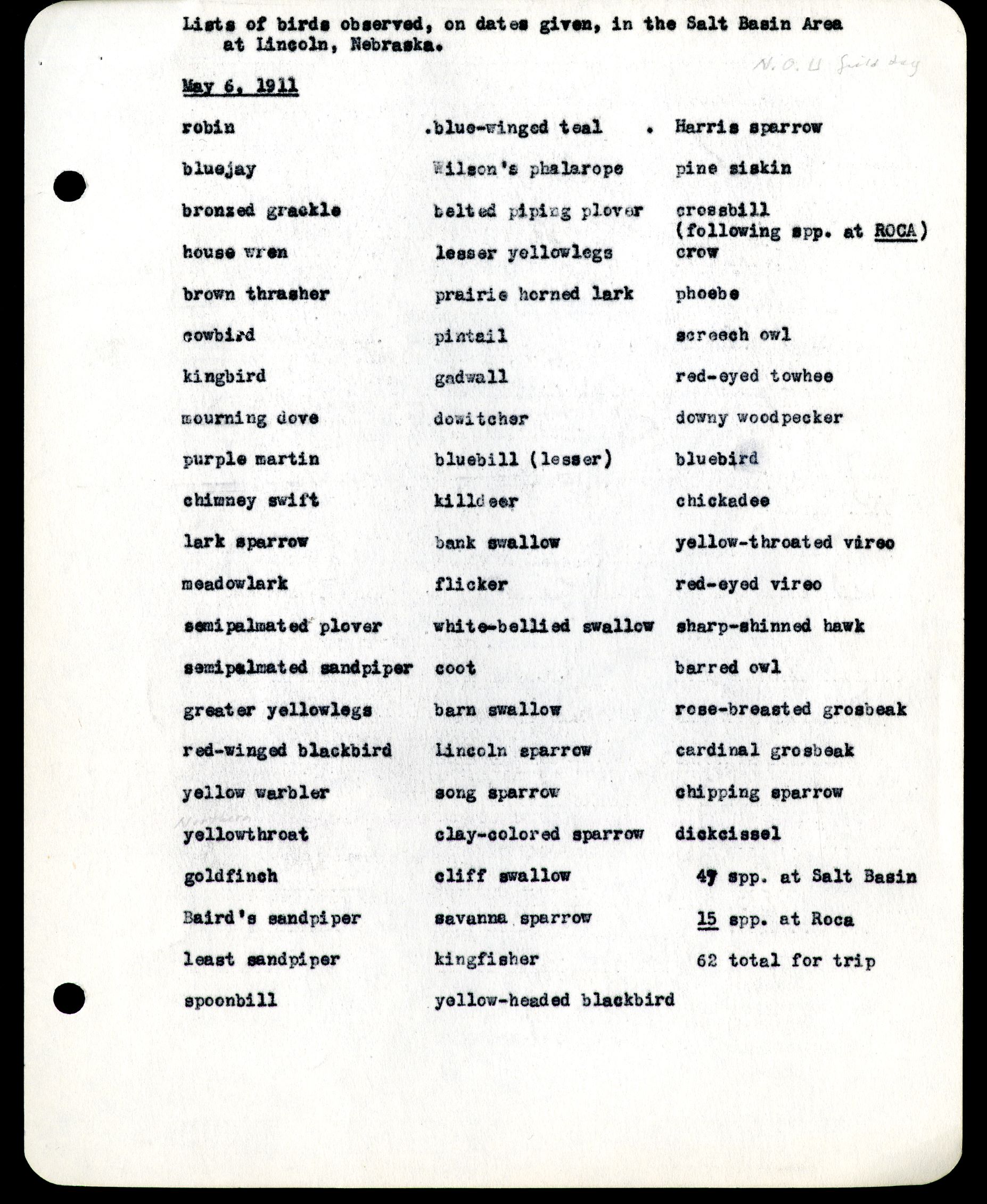

Lists of birds observed, on dates given, in the Salt Basin Area at Lincoln, Nebraska

Lists of birds observed, on dates given, in the Salt Basin Area at Lincoln, Nebraska

May 6, 1911

catbird Blue-winged teal Harris sparrow

bluejay Wilson’s phalarope pine siskin

bronzed grackle belted piping plover crossbill (following spp. at ROGA)

house wren lesser yellowlegs crow

catbird Blue-winged teal Harris sparrow

brown thrasher praire horned lark phoebe

cowbird pintail screech owl

kingbird gadwell red-eyed towhee

mourning dove dowitcher downy woodpecker

purple martin blue (lesser) bluebird

chimney swift killdeer chickadee

lark sparrow bank swallow yellow-throated vireo

meadowlark flicker red-eyed vireo

semipalmated plover white-bellied swallow sharp-shinned hawk

semipalmated sandpiper coot barred owl

greater yellowlegs barn swallow rose-breasted grosbeak

red-winged blackbird Lincoln sparrow cardinal grosbeak

yellow warbler song sparrow chipping sparrow

yellowthroat clay-colored sparrow dickcissel

goldfinch cliff swallow 49 spp. at Salt Basin

Baird’s sandpiper savanna sparrow 15 spp. at Roca

least sandpiper kingfisher 62 total for trip

spoonbill yellow-headed blackbird

Lists of birds observed, on dates given, in the Salt Basin Area at Lincoln, Nebraska

Lists of birds observed, on dates given, in the Salt Basin Area at Lincoln, Nebraska

May 6, 1911

catbird Blue-winged teal Harris sparrow

bluejay Wilson’s phalarope pine siskin

bronzed grackle belted piping plover crossbill (following spp. at ROGA)

house wren lesser yellowlegs crow

catbird Blue-winged teal Harris sparrow

brown thrasher praire horned lark phoebe

cowbird pintail screech owl

kingbird gadwell red-eyed towhee

mourning dove dowitcher downy woodpecker

purple martin blue (lesser) bluebird

chimney swift killdeer chickadee

lark sparrow bank swallow yellow-throated vireo

meadowlark flicker red-eyed vireo

semipalmated plover white-bellied swallow sharp-shinned hawk

semipalmated sandpiper coot barred owl

greater yellowlegs barn swallow rose-breasted grosbeak

red-winged blackbird Lincoln sparrow cardinal grosbeak

yellow warbler song sparrow chipping sparrow

yellowthroat clay-colored sparrow dickcissel

goldfinch cliff swallow 49 spp. at Salt Basin

Baird’s sandpiper savanna sparrow 15 spp. at Roca

least sandpiper kingfisher 62 total for trip

spoonbill yellow-headed blackbird

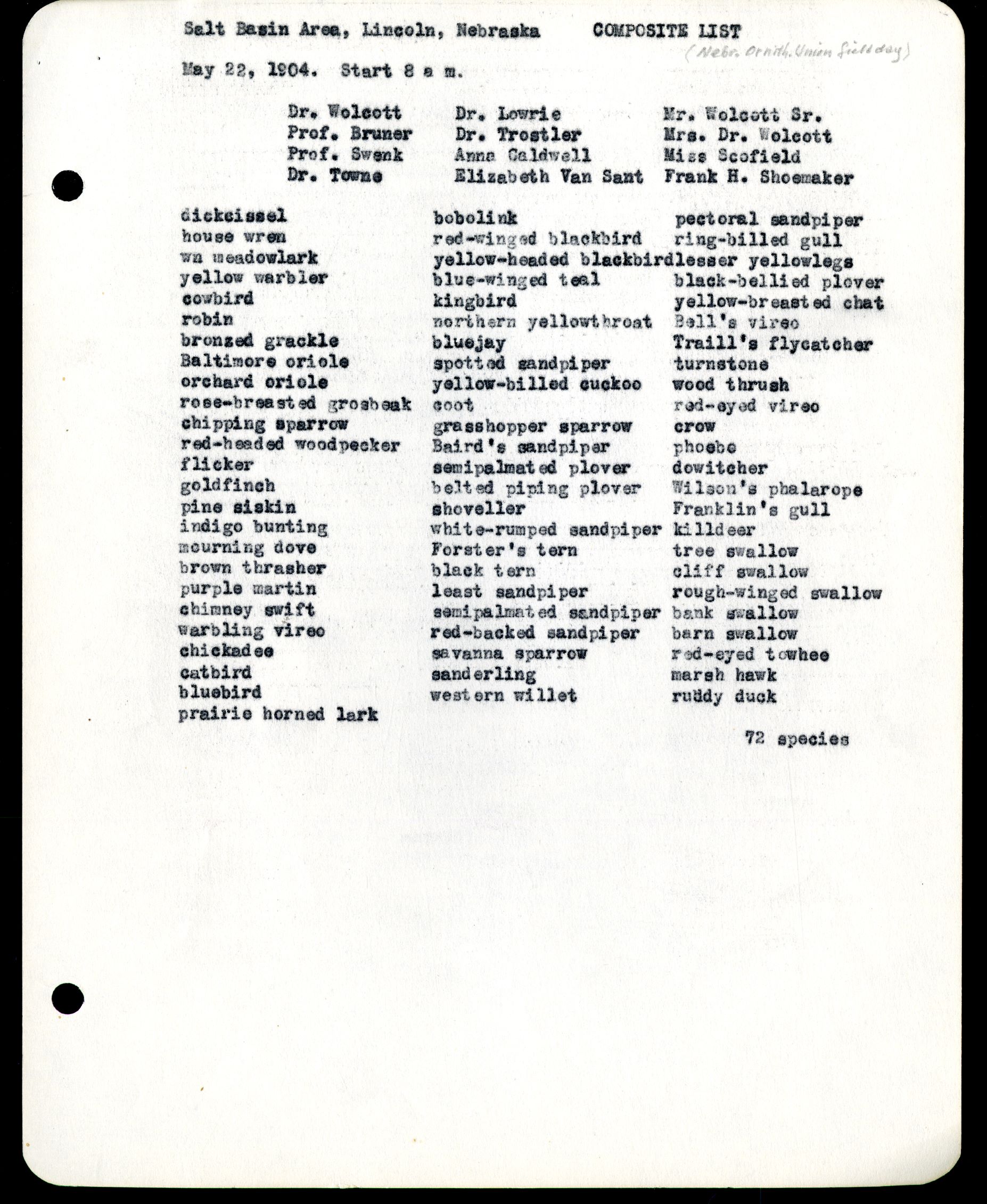

Salt Basin Area, Lincoln, Nebraska

Salt Basin Area, Lincoln, Nebraska

May 7, 1911

robin rough-winged swallow warbling vireo

yellow warbler tree swallow chickadee

meadowlark Harris sparrow bobwhite

yellowlegs brown thrasher ring-billed gull

Baird’s sandpiper dickcissel white-crowned sparrow

semipalmated sandpiper yellowthroat downy woodpecker

red-winged blackbird bluejay bluebird

semipalmated plover yellow-headed blackbird green heron

prairie horned lark house wren American bittern

crow rose-breasted grosbeak Forster’s tern

least sandpiper catbird Hutchins’ goose

blue-winged teal Baltimore oriole lesser bluebill

stilt sandpiper least flycatcher whooping crane

cowbird wood thrush killdeer

kingbird screech owl kingfisher

chimney swift red-eyed towhee spotted sandpiper

mourning dove myrtle warbler Franklin’s gull

spoonbill pine siskin grasshopper sparrow

bank swallow orange-crowned warbler clay-colored sparrow

barn swallow red-headed woodpecker Arkansas kingbird

goldfinch bronzed grackle 62 species

Salt Basin Area, Lincoln, Nebraska COMPOSITE LIST (Nebr. Ornith. Union field day)

Salt Basin Area, Lincoln, Nebraska COMPOSITE LIST (Nebr. Ornith. Union field day)

May 22, 1904. Start 8 a.m.

Dr. Wolcott Dr. Lowrie Mr. Wolcott Sr.

Prof. Bruner Dr. Torstler Mrs. Dr. Wolcott

Prof. Swenk Anna Caldwell Miss Scofield

Dr. Towne Elizabeth Van Sant Frank H. Shoemaker

dickcissel bobolink pectoral sandpiper

house wren red-winged blackbird ring-billed gull

wn meadowlark yellow-headed blackbird lesser yellowlegs

yellow warbler blue-winged teal black-bellied ployer

robin northern yellowthroat Bell’s vireo

bronzed grackle bluejay Traill’s flycatcher

Baltimore oriole spotted sandpiper turnstone

orchard oriole yellow-billed cuckoo wood thrush

rose-breasted gorsbeak coot red-eyed vireo

chipping sparrow grasshopper sparrow crow

red-headed woodpecker Baird’s sandpiper phoebe

flicker semipalmated plover dowitcher

goldfinch belted piping plover Wilson’s phalarope

pine siskin shoveller Franklin’s gull

indigo bunting white-rumped sandpiper killdeer

mourning dove Forster’s tern tree swallow

brown thrasher black tern cliff swallow

purple martin least sandpiper rough-winged swallow

warbling vireo semipalmated sandpiper bank swallow

chickadee savanna sparrow red-eyed towhee

catbird sanderling marsh hawk

bluebird western willet ruddy duck

prairie horned lark 72 species

yellow warbler

orchard oriole

catbird

Bell’s vireo

yellowthroat

red-winged blackbird

yellow-headed blackbird

wn. field sparrow

yellow-billed cukoo

brown thrasher

Traill’s flycatcher

goldfinch

red-eyed towhee

coot

long-billed marsh wren

bank swallow

bluebird

indigo bunting

wn. house wren

kingbird

warbling vireo

21 species

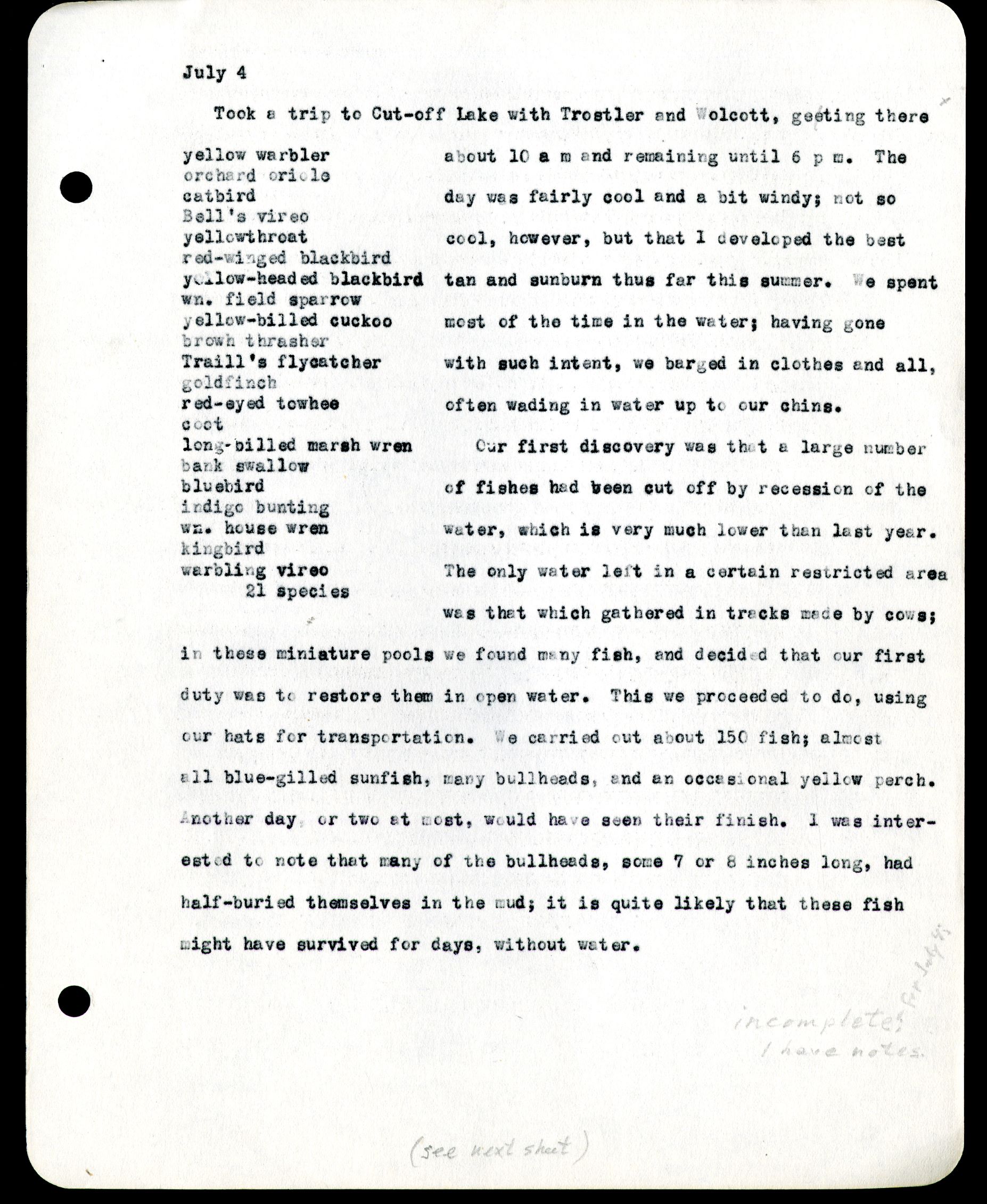

Took a trip to Cut-off Lake with Trostelr and Wolcott, getting there about 10 a m and remaining until 6 p m. The day was fairly cool and a bit windy; not so cool, however, but that I developed the best tan and sunburn thus far this summer. We spent most of the time in the water; having gone with such intent, we barged in clothes and all, often wading in water up to our chins.

Our first discovery was that a large number of fishes had been cut off by recession of the water, which is very much lower than last year. The only water left in a certain restricted area was that which gathered in tracks made by cows; in these miniature pools we found many fish, and decided that our first duty was to restore them in open water. This we proceeded to do, using our hats for transportation. We carried out about 150 fish, almost all blue-gilled sunfish, many bullheads, some 7 or 8 inches long, had half-buried themselves in the mud; it is quite likely that these fish might have survived for days, without water.

Elizabeth Van Sant Field Notes, May 1899

From field notes of Elizabeth Van Sant, while on a vacation in Kansas

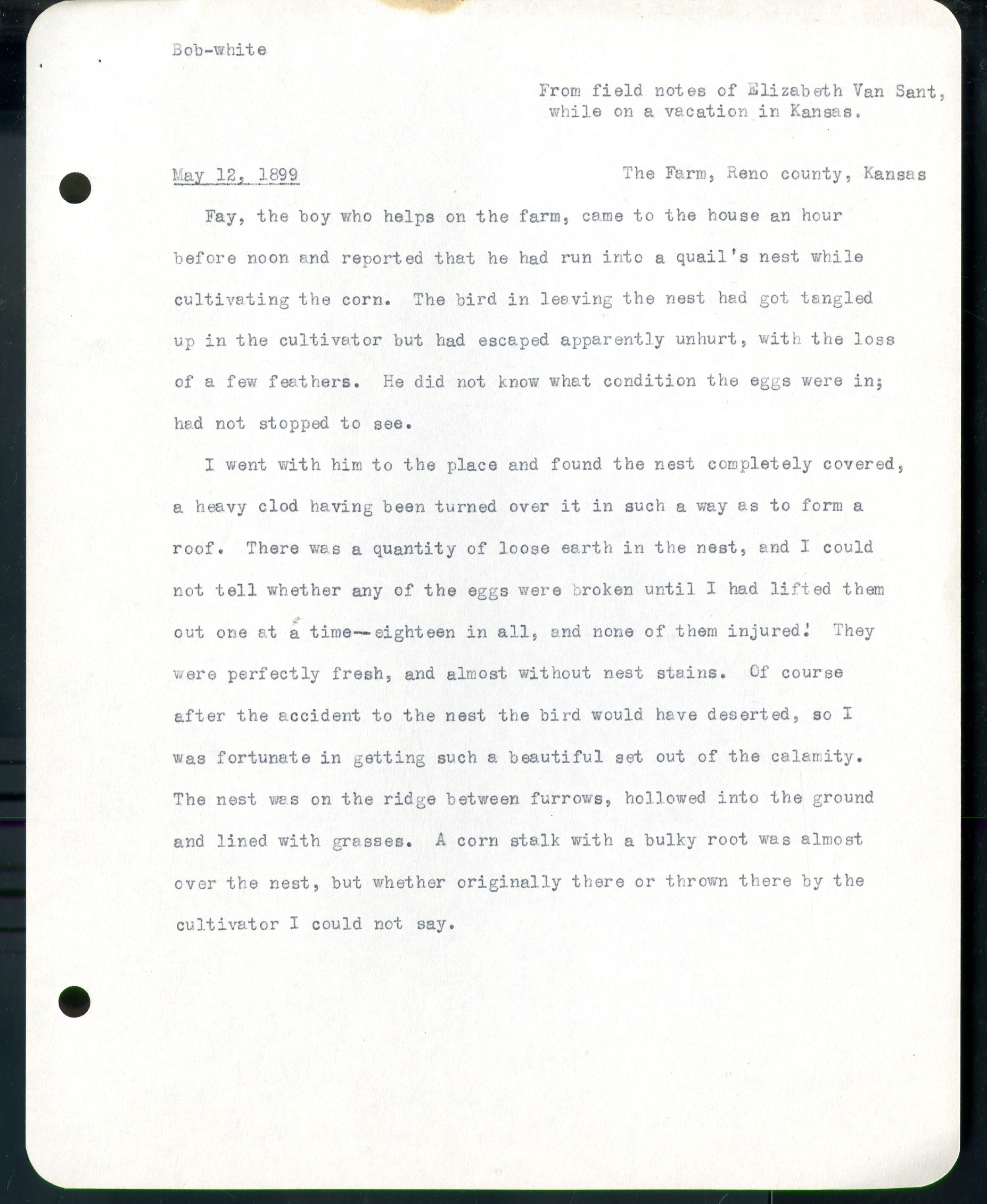

May 12, 1899 The Farm, Reno County, Kansas

Fay, the boy who helps on the farm, came to the house an hour before noon and reported that he had run into a quail’s nest while cultivating the corn. The bird in leaving the nest had got tangled up in the cultivator but had escaped apparently unhurt, with the loss of a few feathers. He did not know what condition the eggs were in; had not stopped to see.

I went with him to the place and found the nest completely covered, a heavy clod having been turned over it in such a way as to form a roof. There was a quantity of loose earth in the nest, and I could not tell whether any of the eggs were broken until I had lifted them out one at a time – eighteen in all, and none of them injured! They were perfectly fresh, and almost without nest stains. Of course after the accident to the nest the bird would have deserted, so I was fortunate in getting such a beautiful set out of the calamity. The nest was on the ridge between furrows, hollowed into the ground and lined with grasses. A corn stalk with a bulky root was almost over the nest, but whether originally there or thrown there by the cultivator I could not say.

Pinnated Grouse Story, March 1892

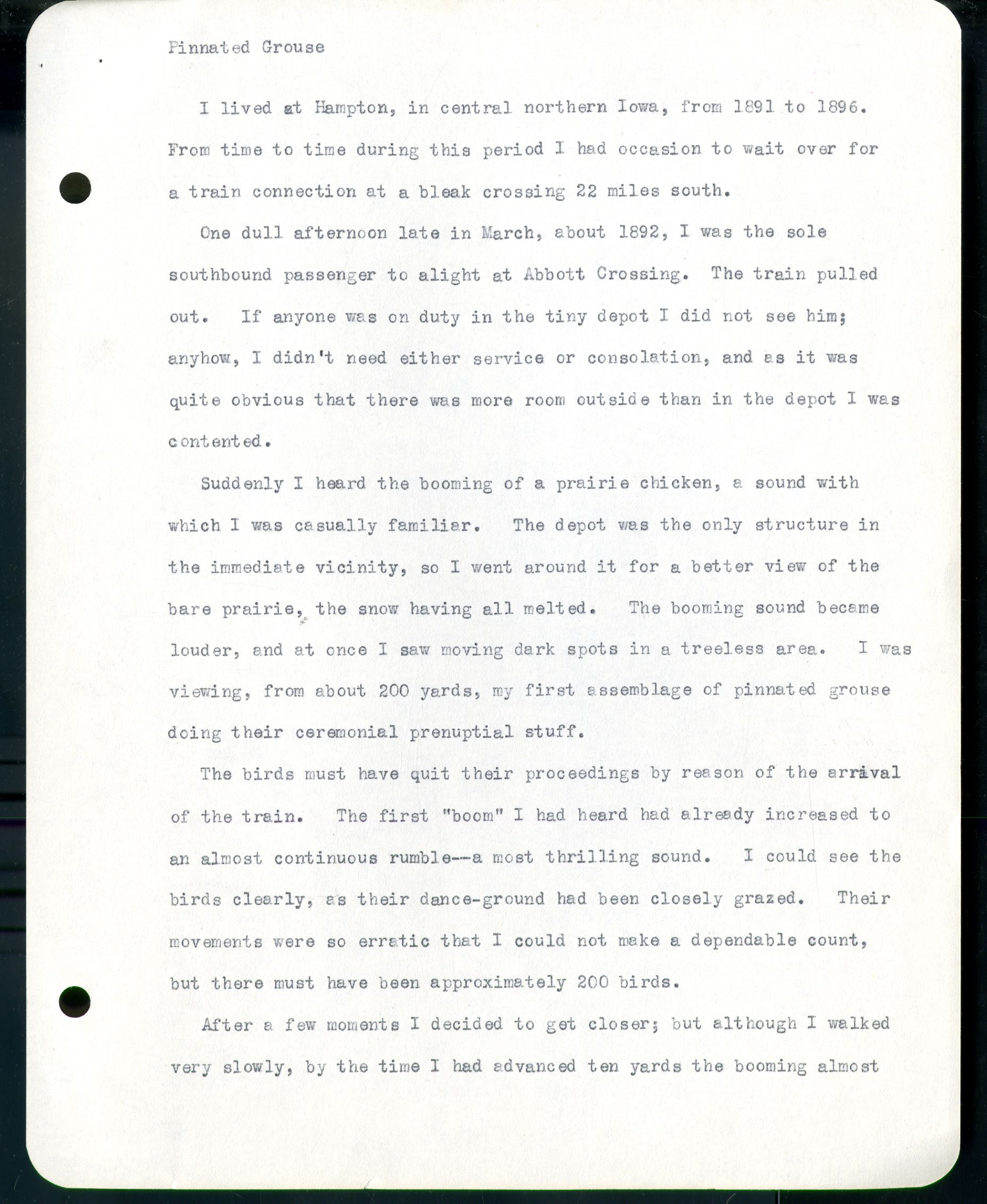

Pinnated grouse

Pinnated grouse

I lived in Hampton, in central northern Iowa, from 1891 to 1896. From time to time during this period I had occasion to wait over for a train connection at a bleak crossing 22 miles south.

One dull afternoon late in March, about 1892, I was the sole eastbound passenger to alight at Abbott Crossing. The train pulled out. If anyone was on duty in the tiny depot I did not see him; anyhow, I didn’t need either service or consolation, and as it was quite obvious that there was more room outside than in the depot I was contented.

Suddenly I heard the booming of a prairie chicken, a sound with which I was casually familiar. The depot was the only structure in the immediate vicinity, so I went around it for a better view of the bare prairie, the snow having all melted. The booming sound became louder, and at once I saw moving dark spots in a treeless area. I was viewing, from about 200 yards, my first assemblage of pinnated grouse doing their ceremonial prenuptial stuff.

The birds must have quit their proceedings by reason of the arrival of the train. The first “boom” I had heard had already increased to an almost continuous rumble – a most thrilling sound. I could see the birds clearly, as their dance-ground had been closely grazed. Their movements were so erratic that I could not make a dependable count, but there must have been approximately 200 birds.

After a few moments I decided to get close; but although I walked very slowly, by the time I had advanced ten yards the booming almost

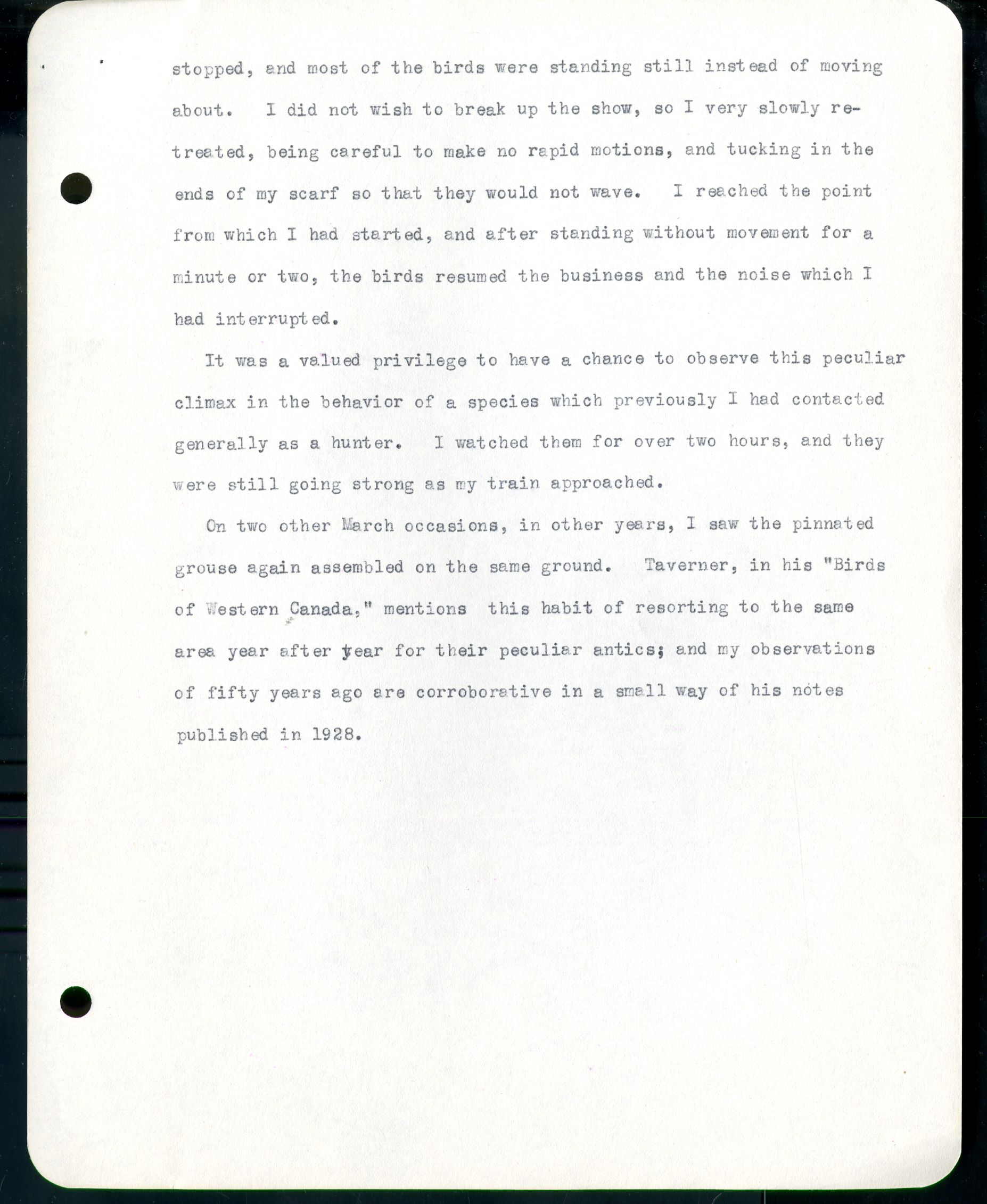

stopped, and most of the birds were standing still instead of moving about. I did not wish to break up the show, so I very slowly retreated, being careful to make no rapid motions, and tucking in the ends of my scarf so that they would not wave. I reached the point from which I had started, and after standing without movement for a minute or two, the birds resumed the business and the noise which I had interrupted.

stopped, and most of the birds were standing still instead of moving about. I did not wish to break up the show, so I very slowly retreated, being careful to make no rapid motions, and tucking in the ends of my scarf so that they would not wave. I reached the point from which I had started, and after standing without movement for a minute or two, the birds resumed the business and the noise which I had interrupted.

It was a valued privilege to have a chance to observe this particular climax in the behavior of a species which previously I had contacted generally as a hunter. I watched them for over two hours, and they were still going strong as my train approached.

On two other March occasions, in other years, I saw the pinnated grouse again assembled on the same ground. Taverner, in his “Birds of Western Canada,” mentions this habit of resorting to the same area year after year for their peculiar antics; and my observations of fifty years ago are corroborative in a small way of his notes published in 1928.

White Clover Story, Sept. – Oct. 1931

1931

1931

Omaha, Nebraska

Sept. 5 – Oct 10, 1931

I took up and carried home on September 5th, a sod of white clover (Trifolium repens L.) plants from a lawn which I had had under observation for several weeks, near the corner of Martha and S. 29th Streets. The square of sod taken was cut with great care, 6 by 7 inches, and 3 inches deep to favor the roots.

This bluegrass-and-clover lawn was well kept and often watered, and was subject to frequent cutting with a lawn mower. The clover colony which interested me was a small part of a small area from which bluegrass had been entirely crowded out, and lay in such position, just inside the curbing, that persons leaving or entering their cars were quite likely to step on the plants. – These inconsequential points are recorded for the reason that they are the only known unusual stimuli to which the plants had been subjected, and may conceivably have some bearing upon the abnormality of this little clover colony.

At the time of taking up this small sod, September 5th, after it had been spared mowing at my request for about a month, it showed nearly as many four-leaved and five-leaved clovers as of the normal three-leaved form. It was not practicable to examine the youngest of the unopened leaves, as they might be injured by the process; but as careful a check of them as I could make, using a slightly blunted No. 10 needle with its head set into a delicately tapered pine handle for convenience, disclosed a total, of opened and determinable opening leaves, of between 60 and 70 4’s, and over 40 5’s. The normal leaves (having 3 leaflets) were not

(Omaha, Nebraska

(Omaha, Nebraska(Sept. 5 – Oct. 10, 1931

as carefully checked as the others, but numbered approximately 125-130.

On September 6th I took a 5×7 photograph, directly downward, of the colony of plants in the small sod taken up. On the 7th, 48 hours after removal from the lawn, it was in thriving condition, only a few sprats on the edges having withered by reason of cut roots.

I kept this botanical treasure in the shady privacy of the back yard, open to early morning sunshine and to rain, half concealed by sprays of Lycium. There being only two or three blossoms and those stunted, it was my plan to gather seed early in the coming summer, to ascertain whether they might carry on the odd leaf habit. I kept it supplied with water when rain failed. On October 1st it was still in excellent condition.

However, during the first week in October, some trespasser found the sod of plants and calmly cut it in two; most considerately carrying away only a half, but so clumsily disturbing the remaining roots that they soon dried out and died.

Wild Peanuts around Lincoln and Omaha, Sept. 1920

1920

1920Lincoln, Nebraska

Sept. 15, 1920

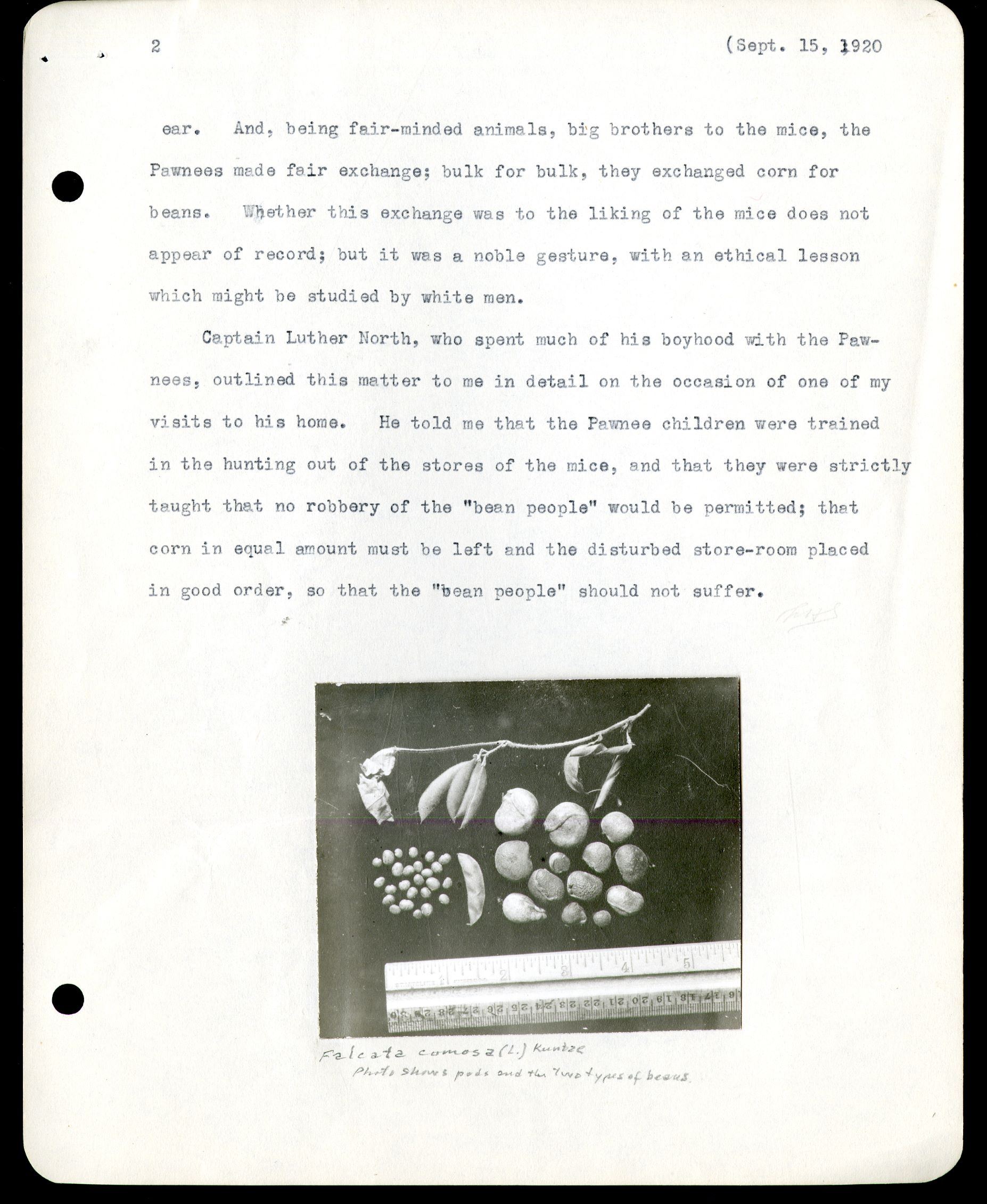

The Wild Peanut is a very common vine in the woodland about Lincoln and Omaha, though its best growth occurs farther east under more humid conditions. The vines, decumbent or climbing, reach a length of six or eight feet; the leaves have three leaflets, oval with rounded base and acute apex, dark green in color, and covered with a slight pubescence. This vine belongs to the pea family, and has tiny white or lavender pea-like blossoms in short axillary racemes. It is known botanically as Falcata comosa.

This vine bears two kinds of beans. Those borne above the ground, in pea-like pods 1½ inches long, are bean-shaped, and only 3/16 inch long. The others are derived from solitary flowers on creeping branches from the base; these are about the size and shape of a Lima bean, and are found just below the ground surface. These buried beans are rooted out by swine; “hog peanut” is the farmer’s name for the plant.

The Pawnee Indians were accustomed to gather these beans, of both types, as a part of their winter store. But their gathering was too long a task. It happens that the meadow mice also store these beans for winter use; and, having much more time to spare than the Indians, are far more successful in gathering the crop. So the Indians took the direct method of helping themselves from the hoarded supplies of the mice.

The Pawnees raised corn of a most peculiar varicolored type – blue, purple, red, white, and a whole range of intermediate colors, all on one

2 (Sept. 15, 1920

2 (Sept. 15, 1920

ear. And, being fair-minded animals, big brothers to the mice, the Pawnees made fair exchange; bulk for bulk, they exchanged corn for beans. Whether this exchange was to the liking of the mice does not appear of record; but it was a noble gesture, with an ethical lesson which might be studied by white men.

Captain Luther North, who spent much of his boyhood with the Pawnees, outlined this matter to me in detail on the occasion of one of my visits to his home. He told me that the Pawnee children were trained in the hunting out of the stores of the mice, and that they were strictly taught that no robbery of the “bean people” would be permitted; that corn in equal amount must be left and the disturbed store-room placed in good order, so that the “bean people” should not suffer.

[A photograph]

Falcata comosa (L) Kuntza

Photo shows pods and the two types of beans

1925 Botanical Note

8

8A botanical (mebbe ethnobotanical)

note from my 1925 fieldbook.

My first acquaintance with the tuberous sunflower (“Jerusalem artichoke”) was in the Omaha area, about 1904. On two or three occasions I carried home in the autumn from northeastern Sarpy county messes or the tubers, and Quiz ventured their preparation in a sort of stew, or perhaps it was a full-bodied soup. The tubers when cooked had about the consistency of sweet potatoes, but we found them practically without flavor – certainly without a distinctive taste as afforded by the sweet potato or other common root foods such as turnip, carrot, or parsnip. We were a bit disappointed.

In 1925 I was a member of a small party which drove to the Fort Berthold reservation of the Arikara Indians in North Dakota: Dr. H. B. Alexander and Prof. M. R. Gilmore, then of the University of Nebraska; Keene Abbott, dramatic editor on the Omaha World-Herald staff; Coffin, taking motion pictures for the Heye Foundation; and two or three others. On one occasion our cordial Arikara tubers. Bits of meat were cooked with it; and we found it excellent.

The next day I derived certain intimate facts from a tribe member who could talk my language. . . . To white men in general, I dare say, dog-meat is something which is gained from a meat-counter for a definite and obvious use consummated in the back yard, to the great delight of Fido. But with the Arikara, the significance of the words is startlingly different. It was a positive and lasting joy to me, to impart my learning to Alexander and Abbott, and to note their reactions.

When I returned to Omaha I told Quiz about my findings as to the ingredient which could give flavor and meaning to a soup made from the roots of the tuberous sunflower; and I suggested that I gather and that she cook up a mess, applying my newly acquired knowledge. It was quite disconcerting, so finely cooperative was she generally in support or furtherance of my experiments and notions, to meet with a definite refusal. However, it is but fair to explain that she had only Pretzel, a fox terrier, and Frazzle, who was just a dog; and after careful thought I could appreciate the possibility that she might have been actuated by purely sentimental reasons.